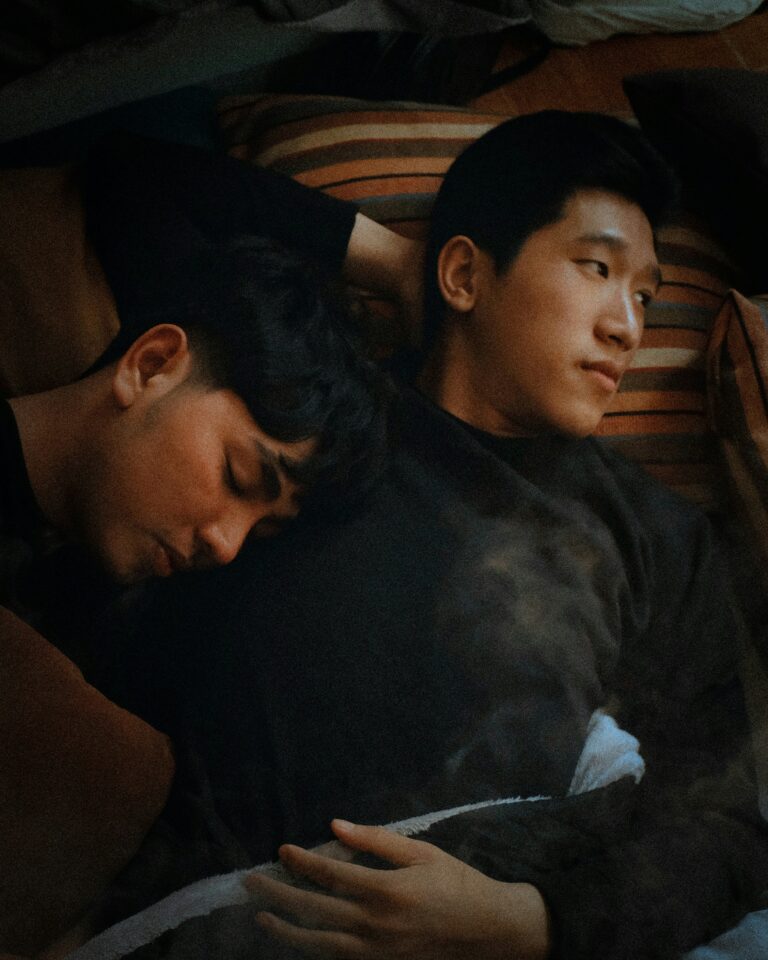

Why do some people dive headfirst into relationships, while others tiptoe cautiously, fearing the emotional plunge? Might it be courage, fear, or something deeper that shapes the ways in which we navigate love?

Why do some people dive headfirst into relationships, while others tiptoe cautiously, fearing the emotional plunge? Might it be courage, fear, or something deeper that shapes the ways in which we navigate love?

Relationships are an inherently risky commitment. They ask us to be vulnerable, to trust another with our emotions, and to risk our hearts in ways that can feel exhilarating and equally as terrifying. Whether it’s expressing love, sharing our fears, or committing fully to another, every step requires us to delicately navigate the balance between connection and self-protection. To understand why we each approach these relational risks so differently, we may turn to attachment theory as a guiding force for uncovering the underlying patterns that shape our emotional bonds and interpersonal dynamics. Attachment theory, developed by John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth in the 1950s, explores how early emotional bonds with caregivers shape social and emotional development (Simpson & Beckes, 2023). It identifies four distinct attachment styles – secure, anxious-ambivalent, avoidant-dismissive, and disorganized – each characterized by distinct interaction patterns (The Attachment Project, 2024).

But how do these distinct attachment styles influence our lives? Secure attachment, the most common style at around 50% of the population, is marked by confidence in forming relationships, comfort with intimacy, and a healthy balance between independence and dependence (Cherry, 2023). Anxious-ambivalent individuals (10%) often appear emotionally intense, craving closeness and reassurance, fearing rejection, and experiencing heightened relationship anxiety (Mandriota, 2024). Avoidant-dismissive individuals (15%) prioritize independence, often avoiding emotional closeness altogether, and struggling with vulnerability. Disorganized attachment, seen in 25% of the population, involves conflicting behaviors, alternating between seeking closeness and avoiding it, often rooted in fear or early trauma

Now I’m sure all of us reading this likely felt one of these styles lead off the page, resonating deeply with our own experiences or those of someone we know. This connection is not coincidental – the attachment styles we each carry profoundly shape how we perceive and navigate the inherent risks of emotional vulnerability in relationships, influencing everything from how we build trust to how we handle conflict and intimacy.

For those with a secure attachment style, emotional risks are approached with confidence, underpinned by a fundamental belief that relationships are a safe space. These individuals don’t shy away from conflict, viewing it as an essential component of love to be resolved collaboratively, rather than as a threat. In contrast, others may carry a heightened sensitivity to risk – those with anxious attachment styles might see small disagreements or delayed responses as signs of rejection, which can lead to behaviors like seeking constant reassurance. While this reassurance-seeking may offer temporary relief, it can inadvertently amplify the very risks it seeks to soothe, further straining the relationship over time. The deeply rooted fear of abandonment these individuals often experience amplifies even minor relational tensions into significant perceived threats. Individuals with anxious attachment styles often exhibit overstimulation and under-regulation of their sympathetic nervous system (Graham, 2008). Neuroimaging research shows heightened activation of the amygdala, a region crucial for triggering sympathetic responses to perceived fear and threat within your environment (Comte, et al., 2024). This increased activity can leave them feeling overwhelmed with stress or panic over minor relational tensions, whilst unable to self-regulate enough to activate the calming influence of the parasympathetic nervous system. With their fight-or-flight response in overdrive, they may find themselves at a crossroads—exploding at their partner in a desperate bid for reassurance, or withdrawing in fear, paralyzed by the intensity of their emotions and the perceived threat to the relationship.

“Although secure attachment can sound out of reach or like a fantasy goal for many of us, it’s how we’re fundamentally designed to operate

-Diane Poole Heller”

On the other hand, avoidant individuals often see closeness itself as the risk in a relationship, guarding their independence by keeping others at a safe distance. Vulnerability can feel like losing control, which may lead to withdrawal. Neuroimaging studies have shown that avoidant individuals tend to exhibit reduced activation in the ventral striatum, a region linked to reward and social connection, which alludes to their discomfort with closeness and reliance on emotional detachment as a protective mechanism (Comte, et al., 2024). Meanwhile, those with a more disorganized attachment style experience a complicated “push-and-pull” dynamic – seeking connection but retreating when it feels too overwhelming or unsafe. This erratic perception of risk is often shaped by past experiences of fear or inconsistency in relationships, which leave a lasting imprint on their biological stress systems. Research indicates that individuals with disorganized attachment also frequently display heightened activation of the amygdala, contributing to feelings of unsafety in relationships (Comte, et al., 2024). Additionally, dysregulated activity in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis leads to inconsistent stress responses, causing emotional arousal to spike unpredictably. This instability mirrors their behavioral tendencies: a desire for closeness can quickly shift to withdrawal or avoidance when the intensity of their emotions becomes unmanageable.

Does this mean we’re all doomed to perpetually repeat the patterns of our attachment styles forever? Don’t lose all hope just yet – there might just be a way for us to rewrite the script and create healthier, more secure relationships. We must turn to one of the most fundamental elements in navigating relational risk: trust. Trust acts as the safety net in relationships, either cushioning us against the fear of vulnerability or, when lacking, amplifying those fears into perceived threats (NeuroLaunch, 2024). The ability to build, maintain, and rebuild trust varies accordingly with our attachment styles, playing a pivotal role in holding onto those we love.

For individuals with a secure attachment style, trust serves as a strong foundation, facilitating their confident approach toward relational risks, navigating conflicts collaboratively rather than defensively (Simpson & Overall, 2014). In contrast, those with anxious attachment styles often perceive trust as fragile, easily shaken by minor misunderstandings or perceived threats (Campbell, 2024). Their constant need for reassurance can inadvertently strain relationships, further amplifying their fears. Those with an avoidant attachment style may struggle to trust due to how they equate vulnerability with a loss of independence. They may even go as far as to avoid emotional closeness altogether, creating a self-reinforcing cycle where their reluctance to rely on others prevents trust from ever developing (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). That brings us to those with disorganized attachment styles, which may face perhaps the most complex relationship with trust. Their inner turmoil experienced as a result of their conflicting desires may lead to erratic behaviors—alternating between seeking connection and withdrawing—which can make trust feel both intensely desired and inherently unsafe, often eroding trust over time.

“We must turn to one of the most fundamental elements in navigating relational risk: trust.”

Lucky for us however, rebuilding trust is entirely possible, independent of which style encompasses you. Dr. Susan M. Johnson, a leading expert within attachment theory therapy, emphasizes that consistent, emotionally supportive behaviors can foster trust even in the most insecure attachment styles (Johnson, 2018). Strategies such as open communication, emotional validation, and showing reliability over time are key. Trust requires a collaborative conscious effort between both partners, working towards creating a secure emotional environment where each of our vulnerabilities are met with empathy and patience.

Understanding attachment styles reminds us that while our past experiences shape how we approach relationships, they don’t have to define them. We all carry our own traumas, our own ways of responding to risk and vulnerability. In my relationship, my girlfriend and I have experienced firsthand how our different attachment styles bring unique challenges — she values independence, while I naturally seek reassurance. Yet over time, with mutual understanding and open communication, we’ve learnt that love can transcend these differences. I personally have observed the slow stripping away of some of my own anxious tendencies. Whilst a lot remains – patience and support stands as integral towards further cultivating secure habits.

This serves as a powerful reminder that attachment styles are not as fixed as they seem; they can evolve across a lifetime, especially within the context of a supportive, healthy relationship. Finding the right person—someone who nurtures rather than impedes growth—can play a transformative role in personal development, allowing us to rewrite old patterns and step into more secure versions of ourselves. Relationships are ultimately about embracing the beautiful risk of growing together. By building trust and respecting one another’s needs, one may discover that even two people with distinct attachment patterns can create a strong, lasting foundation. Love, when nurtured, truly has the power to triumph over trauma.

References

- Comte, A., Szymanska, M., Monnin, J., Moulin, T., Nezelof, S., Magnin, E., . . . Vulliez-Coady, L. (2024). Neural correlates of distress and comfort in individuals with avoidant, anxious and secure attachment style: An fMRI study. Attachment & Human Development, 1-23.

- Cherry, K. (2023, December 13). 4 Types of Attachment Styles. Retrieved November 2024, from Very Well Mind: https://www.verywellmind.com/attachment-styles-2795344?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Johnson, S. M. (2018). Attachment Theory in Practice: Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) with Individuals, Couples, and Families (Vol. 1). The Guilford Press.

- Mandriota, M. (2024, November 22). The Link Between Your Attachment Style and Relationships. Retrieved from Psych Central: https://psychcentral.com/health/4-attachment-styles-in-relationships?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- McLeod, S. (2024, January 14). Attachment Theory In Psychology. Retrieved November 2024, from Simply Psychology : https://www.simplypsychology.org/attachment.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. The Guilford Press.

- Simpson, J. A., & Overall, N. C. (2014). Partner buffering of attachment insecurity. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(1), 54-59.

- Simpson, J. A., & Beckes, L. (2023, December 22). attachment theory. Retrieved November 2024, from Encyclopaedia Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/science/attachment-theory?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- The Attachment Project. (2024, August 14). Bowlby and Attachment Theory: Insights and Legacy. Retrieved November 2024, from The Attachment Project: https://www.attachmentproject.com/attachment-theory/john-bowlby/

- Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. (2016, August 30). Attatchment Theory. (i. Encyclopædia Britannica, Producer) Retrieved October 2024, from Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/science/attachment-theory

- Graham, L. (2008, September 5). The Neuroscience of Attachment. Retrieved from Linda Graham, MFT: https://lindagraham-mft.net/the-neuroscience-of-attachment/

- NeuroLaunch. (2024, October 18). Emotional Safety: Building Trust and Security in Relationships. Retrieved from NeuroLaunch: https://neurolaunch.com/emotional-safety/

- Campbell, J. (2024, September 20). Anxious Attachment Style: Causes and Relationship Strategies. Retrieved from NewMiddleClassDad: https://newmiddleclassdad.com/anxious-attachment-style/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Relationships are an inherently risky commitment. They ask us to be vulnerable, to trust another with our emotions, and to risk our hearts in ways that can feel exhilarating and equally as terrifying. Whether it’s expressing love, sharing our fears, or committing fully to another, every step requires us to delicately navigate the balance between connection and self-protection. To understand why we each approach these relational risks so differently, we may turn to attachment theory as a guiding force for uncovering the underlying patterns that shape our emotional bonds and interpersonal dynamics. Attachment theory, developed by John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth in the 1950s, explores how early emotional bonds with caregivers shape social and emotional development (Simpson & Beckes, 2023). It identifies four distinct attachment styles – secure, anxious-ambivalent, avoidant-dismissive, and disorganized – each characterized by distinct interaction patterns (The Attachment Project, 2024).

But how do these distinct attachment styles influence our lives? Secure attachment, the most common style at around 50% of the population, is marked by confidence in forming relationships, comfort with intimacy, and a healthy balance between independence and dependence (Cherry, 2023). Anxious-ambivalent individuals (10%) often appear emotionally intense, craving closeness and reassurance, fearing rejection, and experiencing heightened relationship anxiety (Mandriota, 2024). Avoidant-dismissive individuals (15%) prioritize independence, often avoiding emotional closeness altogether, and struggling with vulnerability. Disorganized attachment, seen in 25% of the population, involves conflicting behaviors, alternating between seeking closeness and avoiding it, often rooted in fear or early trauma

Now I’m sure all of us reading this likely felt one of these styles lead off the page, resonating deeply with our own experiences or those of someone we know. This connection is not coincidental – the attachment styles we each carry profoundly shape how we perceive and navigate the inherent risks of emotional vulnerability in relationships, influencing everything from how we build trust to how we handle conflict and intimacy.

For those with a secure attachment style, emotional risks are approached with confidence, underpinned by a fundamental belief that relationships are a safe space. These individuals don’t shy away from conflict, viewing it as an essential component of love to be resolved collaboratively, rather than as a threat. In contrast, others may carry a heightened sensitivity to risk – those with anxious attachment styles might see small disagreements or delayed responses as signs of rejection, which can lead to behaviors like seeking constant reassurance. While this reassurance-seeking may offer temporary relief, it can inadvertently amplify the very risks it seeks to soothe, further straining the relationship over time. The deeply rooted fear of abandonment these individuals often experience amplifies even minor relational tensions into significant perceived threats. Individuals with anxious attachment styles often exhibit overstimulation and under-regulation of their sympathetic nervous system (Graham, 2008). Neuroimaging research shows heightened activation of the amygdala, a region crucial for triggering sympathetic responses to perceived fear and threat within your environment (Comte, et al., 2024). This increased activity can leave them feeling overwhelmed with stress or panic over minor relational tensions, whilst unable to self-regulate enough to activate the calming influence of the parasympathetic nervous system. With their fight-or-flight response in overdrive, they may find themselves at a crossroads—exploding at their partner in a desperate bid for reassurance, or withdrawing in fear, paralyzed by the intensity of their emotions and the perceived threat to the relationship.

“Although secure attachment can sound out of reach or like a fantasy goal for many of us, it’s how we’re fundamentally designed to operate

-Diane Poole Heller”

On the other hand, avoidant individuals often see closeness itself as the risk in a relationship, guarding their independence by keeping others at a safe distance. Vulnerability can feel like losing control, which may lead to withdrawal. Neuroimaging studies have shown that avoidant individuals tend to exhibit reduced activation in the ventral striatum, a region linked to reward and social connection, which alludes to their discomfort with closeness and reliance on emotional detachment as a protective mechanism (Comte, et al., 2024). Meanwhile, those with a more disorganized attachment style experience a complicated “push-and-pull” dynamic – seeking connection but retreating when it feels too overwhelming or unsafe. This erratic perception of risk is often shaped by past experiences of fear or inconsistency in relationships, which leave a lasting imprint on their biological stress systems. Research indicates that individuals with disorganized attachment also frequently display heightened activation of the amygdala, contributing to feelings of unsafety in relationships (Comte, et al., 2024). Additionally, dysregulated activity in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis leads to inconsistent stress responses, causing emotional arousal to spike unpredictably. This instability mirrors their behavioral tendencies: a desire for closeness can quickly shift to withdrawal or avoidance when the intensity of their emotions becomes unmanageable.

Does this mean we’re all doomed to perpetually repeat the patterns of our attachment styles forever? Don’t lose all hope just yet – there might just be a way for us to rewrite the script and create healthier, more secure relationships. We must turn to one of the most fundamental elements in navigating relational risk: trust. Trust acts as the safety net in relationships, either cushioning us against the fear of vulnerability or, when lacking, amplifying those fears into perceived threats (NeuroLaunch, 2024). The ability to build, maintain, and rebuild trust varies accordingly with our attachment styles, playing a pivotal role in holding onto those we love.

For individuals with a secure attachment style, trust serves as a strong foundation, facilitating their confident approach toward relational risks, navigating conflicts collaboratively rather than defensively (Simpson & Overall, 2014). In contrast, those with anxious attachment styles often perceive trust as fragile, easily shaken by minor misunderstandings or perceived threats (Campbell, 2024). Their constant need for reassurance can inadvertently strain relationships, further amplifying their fears. Those with an avoidant attachment style may struggle to trust due to how they equate vulnerability with a loss of independence. They may even go as far as to avoid emotional closeness altogether, creating a self-reinforcing cycle where their reluctance to rely on others prevents trust from ever developing (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). That brings us to those with disorganized attachment styles, which may face perhaps the most complex relationship with trust. Their inner turmoil experienced as a result of their conflicting desires may lead to erratic behaviors—alternating between seeking connection and withdrawing—which can make trust feel both intensely desired and inherently unsafe, often eroding trust over time.

“We must turn to one of the most fundamental elements in navigating relational risk: trust.”

Lucky for us however, rebuilding trust is entirely possible, independent of which style encompasses you. Dr. Susan M. Johnson, a leading expert within attachment theory therapy, emphasizes that consistent, emotionally supportive behaviors can foster trust even in the most insecure attachment styles (Johnson, 2018). Strategies such as open communication, emotional validation, and showing reliability over time are key. Trust requires a collaborative conscious effort between both partners, working towards creating a secure emotional environment where each of our vulnerabilities are met with empathy and patience.

Understanding attachment styles reminds us that while our past experiences shape how we approach relationships, they don’t have to define them. We all carry our own traumas, our own ways of responding to risk and vulnerability. In my relationship, my girlfriend and I have experienced firsthand how our different attachment styles bring unique challenges — she values independence, while I naturally seek reassurance. Yet over time, with mutual understanding and open communication, we’ve learnt that love can transcend these differences. I personally have observed the slow stripping away of some of my own anxious tendencies. Whilst a lot remains – patience and support stands as integral towards further cultivating secure habits.

This serves as a powerful reminder that attachment styles are not as fixed as they seem; they can evolve across a lifetime, especially within the context of a supportive, healthy relationship. Finding the right person—someone who nurtures rather than impedes growth—can play a transformative role in personal development, allowing us to rewrite old patterns and step into more secure versions of ourselves. Relationships are ultimately about embracing the beautiful risk of growing together. By building trust and respecting one another’s needs, one may discover that even two people with distinct attachment patterns can create a strong, lasting foundation. Love, when nurtured, truly has the power to triumph over trauma.

References

- Comte, A., Szymanska, M., Monnin, J., Moulin, T., Nezelof, S., Magnin, E., . . . Vulliez-Coady, L. (2024). Neural correlates of distress and comfort in individuals with avoidant, anxious and secure attachment style: An fMRI study. Attachment & Human Development, 1-23.

- Cherry, K. (2023, December 13). 4 Types of Attachment Styles. Retrieved November 2024, from Very Well Mind: https://www.verywellmind.com/attachment-styles-2795344?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Johnson, S. M. (2018). Attachment Theory in Practice: Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) with Individuals, Couples, and Families (Vol. 1). The Guilford Press.

- Mandriota, M. (2024, November 22). The Link Between Your Attachment Style and Relationships. Retrieved from Psych Central: https://psychcentral.com/health/4-attachment-styles-in-relationships?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- McLeod, S. (2024, January 14). Attachment Theory In Psychology. Retrieved November 2024, from Simply Psychology : https://www.simplypsychology.org/attachment.html?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2007). Attachment in adulthood: Structure, dynamics, and change. The Guilford Press.

- Simpson, J. A., & Overall, N. C. (2014). Partner buffering of attachment insecurity. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(1), 54-59.

- Simpson, J. A., & Beckes, L. (2023, December 22). attachment theory. Retrieved November 2024, from Encyclopaedia Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/science/attachment-theory?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- The Attachment Project. (2024, August 14). Bowlby and Attachment Theory: Insights and Legacy. Retrieved November 2024, from The Attachment Project: https://www.attachmentproject.com/attachment-theory/john-bowlby/

- Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. (2016, August 30). Attatchment Theory. (i. Encyclopædia Britannica, Producer) Retrieved October 2024, from Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/science/attachment-theory

- Graham, L. (2008, September 5). The Neuroscience of Attachment. Retrieved from Linda Graham, MFT: https://lindagraham-mft.net/the-neuroscience-of-attachment/

- NeuroLaunch. (2024, October 18). Emotional Safety: Building Trust and Security in Relationships. Retrieved from NeuroLaunch: https://neurolaunch.com/emotional-safety/

- Campbell, J. (2024, September 20). Anxious Attachment Style: Causes and Relationship Strategies. Retrieved from NewMiddleClassDad: https://newmiddleclassdad.com/anxious-attachment-style/?utm_source=chatgpt.com