I observe silently as my uncle looks intently at the person talking, concentration evident on his face: eyes squinting, his mouth whispering the words he caught. My instinct is to get his attention and tell him every small message that was just shared, but before I can even lift my hand the conversation has already shifted. While a frown graces my face as a result of frustration and guilt, a small smile appears on his. He is content with the conversation he heard, and his mind finishes the story his ears couldn’t quite. Or, he is preparing a mental list of questions to ask us later. Inspired by my uncle, this article looks at the different ways in which people who are hard of hearing understand language, and consequently communicate with society.

I observe silently as my uncle looks intently at the person talking, concentration evident on his face: eyes squinting, his mouth whispering the words he caught. My instinct is to get his attention and tell him every small message that was just shared, but before I can even lift my hand the conversation has already shifted. While a frown graces my face as a result of frustration and guilt, a small smile appears on his. He is content with the conversation he heard, and his mind finishes the story his ears couldn’t quite. Or, he is preparing a mental list of questions to ask us later. Inspired by my uncle, this article looks at the different ways in which people who are hard of hearing understand language, and consequently communicate with society.

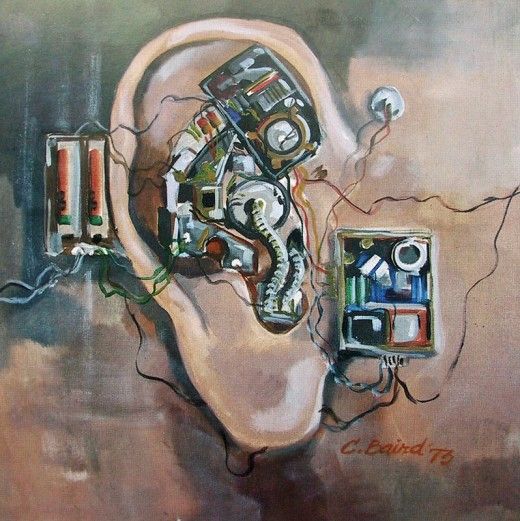

The Mechanical Ear by Chuck Baird (artist who is hard of hearing)

The Mechanical Ear by Chuck Baird (artist who is hard of hearing)

One of the primary functions of language is to be able to communicate with others. Henry Sweet, a phonetician, stated ‘language is the expression of ideas by means of speech-sounds combined into words’ (Crystal, 2021) and so a vital part of being able to use language is hearing these speech-sounds. A person who is hard of hearing has a degree of hearing loss ranging from mild to profound, and therefore has a more difficult time fulfilling this aspect of language (Gasnick, 2021). But does that mean that they cannot effectively use language? Moreover, does it mean that they are unable to communicate with others? Not at all. Research has shown that people who are hard of hearing utilize different methods to understand language and as a result are still able to communicate with society. This article covers six methods: lip reading, sign language, speech language pathologists, hearing devices/cochlear implants, hearing dogs, and other mediums.

LIP READING

Lip reading is a technique that is often used by people who are hard of hearing to understand speech and language by watching lip patterns and the movement of the speaker’s tongue (National Deaf Children’s Society). The variation amongst accuracy of lip reading in people who are hard of hearing can be attributed to practice and knowledge of the language. While lip reading can aid in understanding language, it is not effective when used on its own. Only 30% of spoken English can be accurately lip read due to factors that can hinder the interpretation of the words that are spoken (National Deaf Children’s Society). Some of these factors are accent, lighting, body position, movement, facial hair, and homophones (words that have the same pronunciation but different meanings, like ‘break’ and ‘brake’). If you are not hard of hearing, I am sure you can think of a moment when you have been in a crowded or loud place, and unable to understand what someone near you was saying despite trying to read their lips.

However, research has shown that the use of a technique known as cued speech (CS) is effective for understanding language (Aparicio et al., 2017). CS is a combination of lip reading as well as manual cues. The manual cues are handshapes that represent different sounds, not concepts (like sign language). There are eight handshapes that can be used by the person communicating the manual cues, and the hand will be positioned in one of four places near the mouth. The handshape and hand position helps the person who is hard of hearing to distinguish between speech sounds. The purpose of manual cues is to help identify words that look similar when lip reading, like ‘mat’, ‘bat’, and ‘pat’ (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). Nicholas and Ling (1982, as cited in Bayard et al., 2014) were able to demonstrate the effectiveness of CS on speech perception. Their study showed that participants’ speech perception was 30% to 40% in the lip reading only condition, and went up to 80% with the addition of manual cues to lip reading.

“Hard of hearing’ and ‘deaf’ are the politically correct terms to talk about someone who has partial or full loss of audio. It is less stigmatizing to refer to someone who is hard of hearing as ‘someone who is hard of hearing’ or ‘someone who is deaf’ rather than ‘a hard of hearing person’ or ‘a deaf person.’”

SIGN LANGUAGE

Sign language is another technique that is often used by people who are hard of hearing to understand language and also communicate back. Sign language is a manual and visual way of communication, whereby gestures are used. Gestures are organized in a linguistic way, and each gesture is known as a sign. A sign consists of three parts: handshape, position of hands, and movement of hands. Sign language is unfortunately not universal; people who are hard of hearing from different countries use different sign languages (University of Washington). People who are hard of hearing are thus constrained when they want to communicate with someone hard of hearing from abroad.

A meta study was conducted by researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in order to find out the overlap in activation of brain regions between the processing of sign language in people who are hard of hearing and the processing of spoken language in people who are not hard of hearing. Results showed that Broca’s area, the frontal part of the brain’s left hemisphere, was involved in both signed and spoken language (Trettenbrein et al., 2020). Also the right frontal brain was activated in many of the sign language studies that were evaluated because this region processes non-linguistic aspects like social and spatial information. Examples of non-linguistic aspects would be the signs themselves – movements of the face, body, or hands.

A person who is hard of hearing learns sign language the same way that someone who is not hard of hearing learns a spoken language. From birth, if a child who is hard of hearing is developing around parents and people that use sign language, the child will learn sign language naturally. In fact, from approximately six months of age, a child that is hard of hearing and who is around sign language will start to babble (use of repeated syllables like ‘bababa’ or ‘dadada’) with their hands and around 12 months of age will sign their first word. Similar to spoken language, a child who is hard of hearing makes errors in the production of language. They will sign incorrectly through the wrong handshape or movement, like a child who is not hard of hearing will mispronounce words and sounds. Before the age of two, the child is able to sign words together, forming small statements or sentences. From two to five years of age, head movements and other grammatical aspects like spaces and forming questions are learnt. New vocabulary is discovered throughout the course of a lifetime, just like with spoken language (Schembri, 2015).

SPEECH LANGUAGE PATHOLOGIST

Sign language is a way for someone who is hard of hearing to understand language and also communicate with society through signs. However, people who are hard of hearing can also communicate with society vocally, and this is where a speech language pathologist (SLP) can provide help. Learning how to speak when being hard of hearing is easier for those who learned to talk before becoming hard of hearing compared to those who have been hard of hearing from birth or a young age (Seladi-Schulman, 2020). SLP’s help in multiple ways, and this varies based on age.

With babies and children, the biggest contribution of an SLP lies in assisting parents in managing hearing devices or cochlear implants coupled with the appropriate speech treatment depending on the age of the child, as well as providing counseling for families about the communication options, and offering a flexible treatment (Speech Pathology Master’s Programs, 2020). Data shows that early intervention with SLP’s in children is important for success in communication for the future, with sign and verbal language. With hearing loss that occurs beyond childhood, an SLP helps mostly through providing the person with speech therapy. Speech therapy usually focuses on the production and articulation of the voice for people who are hard of hearing, and can thus enhance multiple parts of the person’s life, including their mental health, independence, and self confidence.

There are various speech therapy techniques that can be used for babies, children, and adults. There are three I will elaborate on, which focus on different channels through which comprehension and communication can occur. The first one is listening and spoken language therapy, which focuses on developing listening skills in order to develop speaking skills through the use of full time hearing devices. The second speech therapy technique is auditory-based, and focuses on developing listening skills, but also teaches to recognise lip reading and visual cues in order to learn language. The third one is speech therapy with total communication approach, which focuses on using spoken language, sign language, and other communication methods like speech generating devices (Nationwide Children’s Hospital). Regardless of which of these three therapies an SLP uses, the inclusion of a hearing device or cochlear implant can aid in treatment.

“A person who is hard of hearing learns sign language the same way that someone who is not hard of hearing learns a spoken language.”

HEARING DEVICES AND COCHLEAR IMPLANT

A hearing device essentially works through amplifying sound (Johns Hopkins Medicine). Most hearing devices have a microphone, which receives the sound. A processor converts the sound received into data and amplifies it. Finally, a receiver sends the amplified sound into the ear. A hearing device is effective as long as the damage to the inner ear is not too great and the hair cells can detect the amplified sound. If the inner ear is too damaged, a hearing aid cannot help in detecting sounds (NIDCD, 2017). In such cases, a cochlear implant could be used. A cochlear implant is fitted surgically, whereas hearing devices are placed on the ear non-surgically. Not everyone is suitable for a cochlear implant, with the requirements constantly changing due to changes in our understanding of the auditory system in relation to the brain (Medline Plus, 2021).

HEARING DOGS

Hearing dogs play many roles in the life of a person who is hard of hearing, with the main one being alerting their owner to important sounds that they might miss. Some examples of these sounds are the fire alarm, door bell, alarm clock, and phone alerts. Another equally important role that hearing dogs play is providing comfort and emotional support to combat loneliness in people who are hard of hearing. Hearing dogs give confidence to their owner, and help them connect with their families, community, friends, and society.

An example of a UK based organization that works with people who are hard of hearing to determine whether a hearing dog would suit their needs is Hearing Dogs for Deaf People. It was heartwarming to read the stories of the people they have helped.

COMMUNICATION VIA OTHER MEDIUMS

As biased as this sounds, I like to think that my uncle is one of the best artists I have come across. His attention to detail and focus while creating woodwork and paintings is unparalleled to anyone I have met. A quote that reminds me of my uncle’s unique perspective is by David Hockney, who said that ‘I actually think deafness makes you see clearer. If you can’t hear, you somehow see.’

In fact, majority of studies seem to indicate that children who are hard of hearing are more nonverbally creative than children who are not hard of hearing (Ebrahim, 2006; Johnson, 1977; Kaltsounis, 1971; Laughton, 1988; Pang & Horrocks, 1968; Silver, 1977, as cited in Stanzione et al., 2013), which might be explained via their strengths in their visual-spatial skills (Blatto-Vallee, Kelly, Gaustad, Porter, & Fonzi, 2007; Marschark & Wauters, 2011, as cited in Stanzione et al., 2013).

When I was younger, I often caught myself wondering how different my uncle’s life would have been if he had full audio perception, how much more information he would have understood in conversations. The older I have grown, I have realized that this was the card he was dealt. While life has definitely thrown him many curveballs as a result of this, he has taken it all in his stride. And this is a greater message to me and everyone who meets him than anything we could have ever filled him in on. <<

References

– Aparicio, M., Peigneux, P., Charlier, B., Balériaux, D., Kavec, M., & Leybaert, J. (2017). The neural basis of speech perception through lipreading and manual cues: Evidence from deaf native users of cued speech. Frontiers in Psychology, 8.

– Bayard, C., Colin, C., & Leybaert, J. (2014). How is the mcgurk effect modulated by cued speech in deaf and hearing adults? Frontiers in Psychology, 5.

– Cochlear implant. (2021, November 30). Medline Plus. Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/007203.htm

– Crystal, D. (2021, December 17). Language. Britannica. Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/language#ref393748

– Cued speech. (2020, June 8). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/hearingloss/parentsguide/building/cued-speech.html

– Gasnick, K. (2021, June 8). Deaf and hard of hearing: What’s the difference? WebMD. Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://www.webmd.com/connect-to-care/hearing-loss/difference-between-deaf-and-hard-of-hearing

– How can hearing aids help? (2017, March 6). National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/hearing-aids

– How do hearing aids work. (n.d.). Johns Hopkins Medicine. Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/hearing-loss/how-do-hearing-aids-work

– Lip-reading [National Deaf Children’s Society]. (n.d.). Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://www.ndcs.org.uk/information-and-support/language-and-communication/spoken-language/supporting-speaking-and-listening/lip-reading/

– Schembri, A. (2015, November 8). How do children learn sign languages? Aussie Deaf Kids. Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://www.aussiedeafkids.org.au/how-do-children-learn-sign-languages.html

– Seladi-Schulman, J. (2020, April 2). How people who are deaf learn to talk. Healthline. Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://www.healthline.com/health/can-deaf-people-talk#about-spoken-language

– SLP roles with patients with hearing impairments. (2020, June 1). Speech Pathology Master’s Programs. Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://speechpathologymastersprograms.com/slp-hearing-impaired-patients/

– Speech services for hearing loss. (n.d.). Nationwide Children’s Hospital. Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://www.nationwidechildrens.org/specialties/hearing-program/speech-services-for-hearing-loss

– Stanzione, C. M., Perez, S. M., & Lederberg, A. R. (2012). Assessing aspects of creativity in deaf and hearing high school students. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 18(2), 228-241.

– Trettenbrein, P. C., Papitto, G., Friederici, A. D., & Zaccarella, E. (2020). Functional neuroanatomy of language without speech: An ALE meta‐analysis of sign language. Human Brain Mapping, 42(3), 699-712.

– What is sign language? (n.d.). University of Washington. Retrieved December 1, 2021, from https://www.washington.edu/accesscomputing/what-sign-language

One of the primary functions of language is to be able to communicate with others. Henry Sweet, a phonetician, stated ‘language is the expression of ideas by means of speech-sounds combined into words’ (Crystal, 2021) and so a vital part of being able to use language is hearing these speech-sounds. A person who is hard of hearing has a degree of hearing loss ranging from mild to profound, and therefore has a more difficult time fulfilling this aspect of language (Gasnick, 2021). But does that mean that they cannot effectively use language? Moreover, does it mean that they are unable to communicate with others? Not at all. Research has shown that people who are hard of hearing utilize different methods to understand language and as a result are still able to communicate with society. This article covers six methods: lip reading, sign language, speech language pathologists, hearing devices/cochlear implants, hearing dogs, and other mediums.

LIP READING

Lip reading is a technique that is often used by people who are hard of hearing to understand speech and language by watching lip patterns and the movement of the speaker’s tongue (National Deaf Children’s Society). The variation amongst accuracy of lip reading in people who are hard of hearing can be attributed to practice and knowledge of the language. While lip reading can aid in understanding language, it is not effective when used on its own. Only 30% of spoken English can be accurately lip read due to factors that can hinder the interpretation of the words that are spoken (National Deaf Children’s Society). Some of these factors are accent, lighting, body position, movement, facial hair, and homophones (words that have the same pronunciation but different meanings, like ‘break’ and ‘brake’). If you are not hard of hearing, I am sure you can think of a moment when you have been in a crowded or loud place, and unable to understand what someone near you was saying despite trying to read their lips.

However, research has shown that the use of a technique known as cued speech (CS) is effective for understanding language (Aparicio et al., 2017). CS is a combination of lip reading as well as manual cues. The manual cues are handshapes that represent different sounds, not concepts (like sign language). There are eight handshapes that can be used by the person communicating the manual cues, and the hand will be positioned in one of four places near the mouth. The handshape and hand position helps the person who is hard of hearing to distinguish between speech sounds. The purpose of manual cues is to help identify words that look similar when lip reading, like ‘mat’, ‘bat’, and ‘pat’ (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). Nicholas and Ling (1982, as cited in Bayard et al., 2014) were able to demonstrate the effectiveness of CS on speech perception. Their study showed that participants’ speech perception was 30% to 40% in the lip reading only condition, and went up to 80% with the addition of manual cues to lip reading.

“Hard of hearing’ and ‘deaf’ are the politically correct terms to talk about someone who has partial or full loss of audio. It is less stigmatizing to refer to someone who is hard of hearing as ‘someone who is hard of hearing’ or ‘someone who is deaf’ rather than ‘a hard of hearing person’ or ‘a deaf person.’”

SIGN LANGUAGE

Sign language is another technique that is often used by people who are hard of hearing to understand language and also communicate back. Sign language is a manual and visual way of communication, whereby gestures are used. Gestures are organized in a linguistic way, and each gesture is known as a sign. A sign consists of three parts: handshape, position of hands, and movement of hands. Sign language is unfortunately not universal; people who are hard of hearing from different countries use different sign languages (University of Washington). People who are hard of hearing are thus constrained when they want to communicate with someone hard of hearing from abroad.

A meta study was conducted by researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in order to find out the overlap in activation of brain regions between the processing of sign language in people who are hard of hearing and the processing of spoken language in people who are not hard of hearing. Results showed that Broca’s area, the frontal part of the brain’s left hemisphere, was involved in both signed and spoken language (Trettenbrein et al., 2020). Also the right frontal brain was activated in many of the sign language studies that were evaluated because this region processes non-linguistic aspects like social and spatial information. Examples of non-linguistic aspects would be the signs themselves – movements of the face, body, or hands.

A person who is hard of hearing learns sign language the same way that someone who is not hard of hearing learns a spoken language. From birth, if a child who is hard of hearing is developing around parents and people that use sign language, the child will learn sign language naturally. In fact, from approximately six months of age, a child that is hard of hearing and who is around sign language will start to babble (use of repeated syllables like ‘bababa’ or ‘dadada’) with their hands and around 12 months of age will sign their first word. Similar to spoken language, a child who is hard of hearing makes errors in the production of language. They will sign incorrectly through the wrong handshape or movement, like a child who is not hard of hearing will mispronounce words and sounds. Before the age of two, the child is able to sign words together, forming small statements or sentences. From two to five years of age, head movements and other grammatical aspects like spaces and forming questions are learnt. New vocabulary is discovered throughout the course of a lifetime, just like with spoken language (Schembri, 2015).

SPEECH LANGUAGE PATHOLOGIST

Sign language is a way for someone who is hard of hearing to understand language and also communicate with society through signs. However, people who are hard of hearing can also communicate with society vocally, and this is where a speech language pathologist (SLP) can provide help. Learning how to speak when being hard of hearing is easier for those who learned to talk before becoming hard of hearing compared to those who have been hard of hearing from birth or a young age (Seladi-Schulman, 2020). SLP’s help in multiple ways, and this varies based on age.

With babies and children, the biggest contribution of an SLP lies in assisting parents in managing hearing devices or cochlear implants coupled with the appropriate speech treatment depending on the age of the child, as well as providing counseling for families about the communication options, and offering a flexible treatment (Speech Pathology Master’s Programs, 2020). Data shows that early intervention with SLP’s in children is important for success in communication for the future, with sign and verbal language. With hearing loss that occurs beyond childhood, an SLP helps mostly through providing the person with speech therapy. Speech therapy usually focuses on the production and articulation of the voice for people who are hard of hearing, and can thus enhance multiple parts of the person’s life, including their mental health, independence, and self confidence.

There are various speech therapy techniques that can be used for babies, children, and adults. There are three I will elaborate on, which focus on different channels through which comprehension and communication can occur. The first one is listening and spoken language therapy, which focuses on developing listening skills in order to develop speaking skills through the use of full time hearing devices. The second speech therapy technique is auditory-based, and focuses on developing listening skills, but also teaches to recognise lip reading and visual cues in order to learn language. The third one is speech therapy with total communication approach, which focuses on using spoken language, sign language, and other communication methods like speech generating devices (Nationwide Children’s Hospital). Regardless of which of these three therapies an SLP uses, the inclusion of a hearing device or cochlear implant can aid in treatment.

“A person who is hard of hearing learns sign language the same way that someone who is not hard of hearing learns a spoken language.”

HEARING DEVICES AND COCHLEAR IMPLANT

A hearing device essentially works through amplifying sound (Johns Hopkins Medicine). Most hearing devices have a microphone, which receives the sound. A processor converts the sound received into data and amplifies it. Finally, a receiver sends the amplified sound into the ear. A hearing device is effective as long as the damage to the inner ear is not too great and the hair cells can detect the amplified sound. If the inner ear is too damaged, a hearing aid cannot help in detecting sounds (NIDCD, 2017). In such cases, a cochlear implant could be used. A cochlear implant is fitted surgically, whereas hearing devices are placed on the ear non-surgically. Not everyone is suitable for a cochlear implant, with the requirements constantly changing due to changes in our understanding of the auditory system in relation to the brain (Medline Plus, 2021).

COMMUNICATION VIA OTHER MEDIUMS

As biased as this sounds, I like to think that my uncle is one of the best artists I have come across. His attention to detail and focus while creating woodwork and paintings is unparalleled to anyone I have met. A quote that reminds me of my uncle’s unique perspective is by David Hockney, who said that ‘I actually think deafness makes you see clearer. If you can’t hear, you somehow see.’

In fact, majority of studies seem to indicate that children who are hard of hearing are more nonverbally creative than children who are not hard of hearing (Ebrahim, 2006; Johnson, 1977; Kaltsounis, 1971; Laughton, 1988; Pang & Horrocks, 1968; Silver, 1977, as cited in Stanzione et al., 2013), which might be explained via their strengths in their visual-spatial skills (Blatto-Vallee, Kelly, Gaustad, Porter, & Fonzi, 2007; Marschark & Wauters, 2011, as cited in Stanzione et al., 2013).

When I was younger, I often caught myself wondering how different my uncle’s life would have been if he had full audio perception, how much more information he would have understood in conversations. The older I have grown, I have realized that this was the card he was dealt. While life has definitely thrown him many curveballs as a result of this, he has taken it all in his stride. And this is a greater message to me and everyone who meets him than anything we could have ever filled him in on. <<

HEARING DOGS

Hearing dogs play many roles in the life of a person who is hard of hearing, with the main one being alerting their owner to important sounds that they might miss. Some examples of these sounds are the fire alarm, door bell, alarm clock, and phone alerts. Another equally important role that hearing dogs play is providing comfort and emotional support to combat loneliness in people who are hard of hearing. Hearing dogs give confidence to their owner, and help them connect with their families, community, friends, and society.

An example of a UK based organization that works with people who are hard of hearing to determine whether a hearing dog would suit their needs is Hearing Dogs for Deaf People. It was heartwarming to read the stories of the people they have helped.