Growing up in Western middle class society in times of globalization, young people have a great amount of freedom of choice. Yet students are found to display higher rates of anxiety and depression. Having an unlimited amount of options to choose from does not always lead to more happiness. It does leave us with a lot of responsibility.

Growing up in Western middle class society in times of globalization, young people have a great amount of freedom of choice. Yet students are found to display higher rates of anxiety and depression. Having an unlimited amount of options to choose from does not always lead to more happiness. It does leave us with a lot of responsibility.

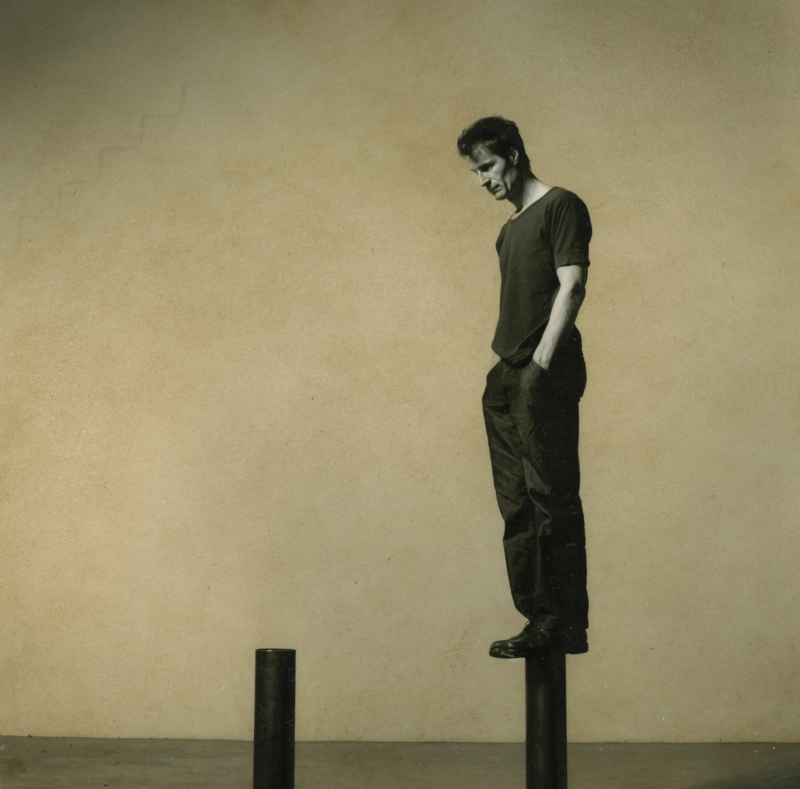

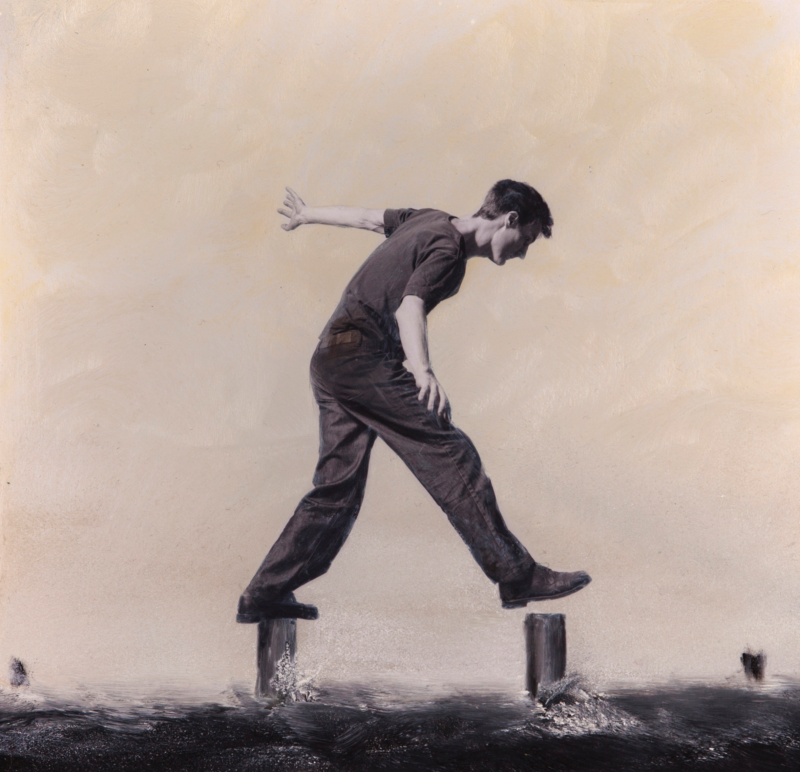

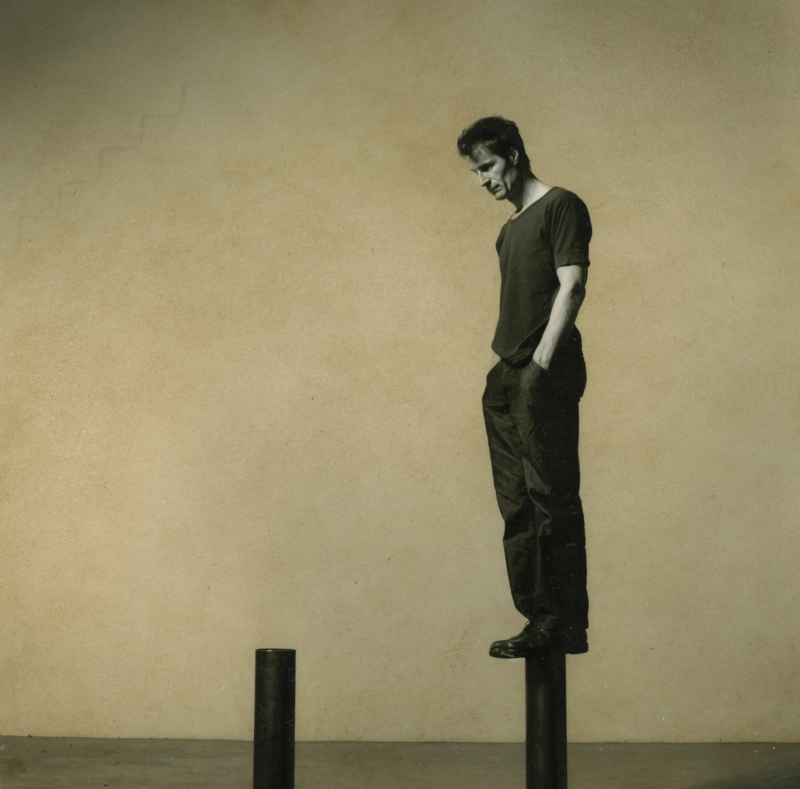

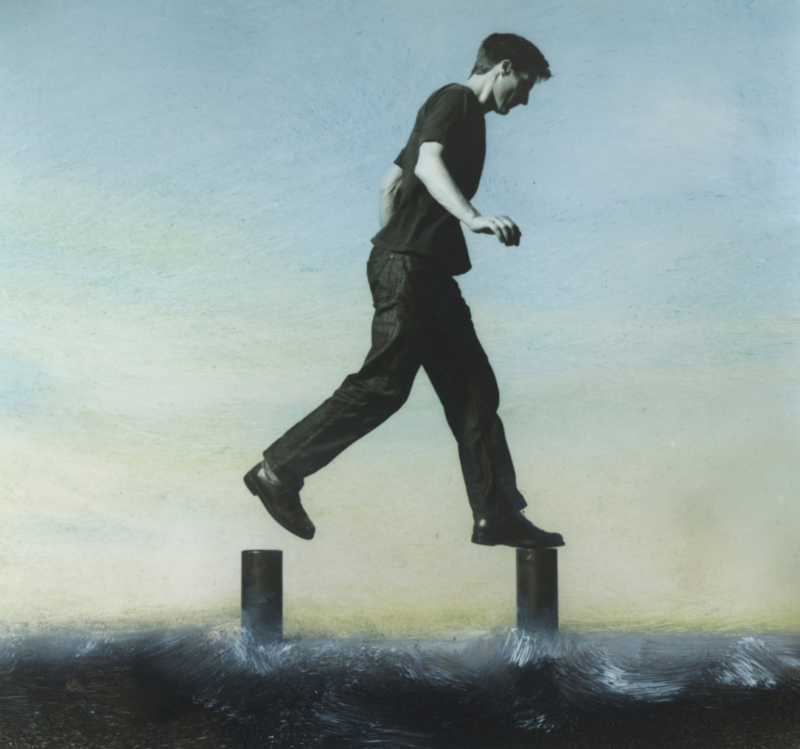

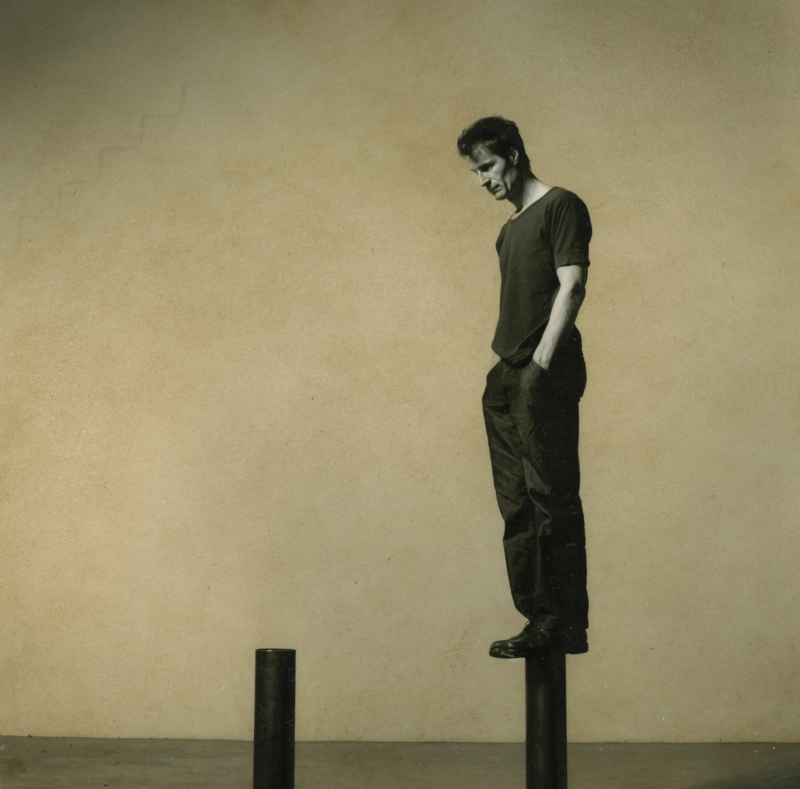

Photos: Rogier Alleblas

‘The official dogma of all Western industrial societies is that if we are interested in maximizing the welfare of our citizens, the way to do that is to maximize individual freedom,’ Barry Schwartz, Professor at the Swarthmore College states in his TED Talk Paradox of Choice (2007). ‘The way to maximize freedom is to maximize freedom of choice. The more choice people have, the more freedom they have.’ I recognize this dogma, it reflects the beliefs I hold. I grew up with the mindset that being as free and independent as possible, and therefore being able to freely choose what I want to do and where I want to be, would maximize my chances of being happy. Combined with a good education, a stable job and income, freedom of choice could hypothetically lead to almost everything I want in life: I could live in any place, become whoever I want to be and have the choice of leaving when I felt like moving on.

Yet, if I look around, a lot of successful people I know are unhappy. I know at least ten people my age who come from comparable socio-economic backgrounds and followed a similar curriculum, but are suffering from depression and anxiety issues. When talking to them, they often seem overwhelmed by the sheer amount of decisions and choices they are asked to make. They are confused, they don’t know what they want from life or what they can expect. All their responsibilities seem to weigh heavily on their shoulders. They wander back to decisions they made in the past, considering the possible outcomes of alternative decisions. They are constantly questioning the present and the future, due to an underlying constant doubt of whether they are on the right path. Are they making the most out of their lives? Or is there something to regret, an untaken chance, a missed train?

“Is there something in the nature of choice, that causes students to suffer from anxiety?”

Various newspaper articles published over the last couple of years support this observation of mine: The number of anxiety and depression issues among students is increasing over the last couple of years. An article published in de Volkskrant in 2018 states that an increasing number of students see their doctor because they are struggling with problems as fatigue, concentration problems, panic attacks, anxiety and addiction (Pieters, 2018). Additionally, Dutch newspaper Trouw writes that about half of the students suffers from anxiety and depression (Kleinjan, 2018) and a research on the study climate at Windesheim University of Applied Sciences found 38,9 percent of all students in the school to suffer from light to medium anxiety and depression issues, and 14,4 percent to suffer from strong anxiety and depression issues (Windesheim, 2017).

At the same time, I observe former primary school classmates of mine that never pursued a higher education, because it was always clear that they would take over the farm or bakery of their parents one day. When I visit the little village in the south of Germany where I grew up, they always seem in balance and satisfied with life. I often thought that I could never be happy living their lives because they never lived abroad, often stayed with one of their first partners and settled down very early – in my opinion, without having had the chance to figure out what else they could have done in life. And yet, talking to them, they never complain, and never seem envious of others. The gap between their objectively more limited freedom of choice, and their perceived higher satisfaction makes me curious: is there something in the nature of choice, that causes some students to suffer from anxiety?

Photos: Rogier Alleblas

Comparing my observations and the research findings, it seems to me that total freedom doesn’t necessarily lead to being a happier person. Rather, it seems that those who had less choice are the ones experiencing less regret or doubt. Is there something in the nature of having to make decisions that can be anxiety-inducing rather than happiness-increasing? The marketing professor Baba Shiv thinks so and says the ability to decide do not always makes us happy (Shiv, 2012). In his TED talk he empathizes the importance of ‘giving up the driver’s seat’ every once in a while. According to him, it is doubt that makes decisions unenjoyable. Research conducted by Sheena Iyengar and Mark Lepper (2000) illustrates this issue by showing that participants that have to choose between 24 different types of jam in a gourmet supermarket are less likely to make a choice at all, unlike participants choosing from only three different types of jam in a small supermarket. Despite being overwhelmed and unable to choose in the big supermarket, participants still choose to go to the big supermarket instead of to the small one. This illustrates that our belief in freedom of choice is ‘[…] so deeply embedded in the water supply, that we don’t even dare to question it’ (Schwartz, 2007). ‘If we can, we choose from the biggest number of possible alternatives because we consider the chance higher to find the best possible option there. At the same time, we are less satisfied with the outcome when we get to choose from a great amount of options, even though from an objective standpoint, the outcome is indeed likely to be better than it would have been if we had less options to choose from. Schwartz illustrates this with an autobiographical example of going to a jeans store that in the past offered only one brand that Schwartz used to buy. These days, the choice of jeans is endless, and in the end he leaves the store with the best fitting jeans he ever owned, but less satisfied, because the jeans are good, but not perfect: ‘The reason that everything was better back when everything was worse, is that when everything was worse, it was actually possible for people to have experiences that were a pleasant surprise’ (Schwartz, 2007).

Sheena Iyengar and Emir Kamenica (2010) demonstrate that the mantra ‘less is more’ doesn’t only impact our satisfaction when shopping for groceries or clothing, but can also have drastic impact on important decisions we have to take in life. A clear example of this is retirement savings choices made by half a million employees of the Vanguard Group. As the employees have too many saving plans to choose from, they don’t make a decision at all in the end and will end up without retirement savings in the future. In order for the company to put money away for them, they would have needed to pick a plan. Since they didn’t, the money is slipping through their fingers and if they fail to put money away themselves on a regular basis, they will not have any retirement savings (Iyengar & Kamenica, 2010). So, no choice makes us unfree, but if we have too many options to choose from, we are often unable to make a decision at all, and if we do, choosing leaves us unsatisfied. What is the ‘golden middle’?

“The mantra 'less is more' impacts important decisions we have to make in life”

‘There is no question that some choice is better that none, but it doesn’t logically follow from that that more choice is better than some’, Schwartz (2007) says. If we have no choice at all, we are unhappy, because we realize we are unfree. Therefore, some choice is wishful. If the options exceed the amount of choice we can handle, this doesn’t lead to happiness either. Therefore, some choice, but not none or unlimited choice, is probably the making us the happiest. The reason, Schwartz explains, is that we have to blame ourselves for the outcome if we had all the choices in the world, and in the end the result wasn’t perfect. Freedom of choice sounds like something that is great to have, but it leaves us with a lot of responsibility. This responsibility can be handled if we are making decisions in a field we are familiar with, but daily life decisions we need to make often exceed our knowledge and overtax us. Schwartz uses the example of patient autonomy, a fabulous sounding term that leaves us with the impression that patients have gained the ability to decide what treatment or medicine is best for them, when being provided with the pros and cons of each option by the doctor. The downside of the freedom to choose is that we as decision makers are not actually knowledgeable enough, at all times, to make a good decision, and so having to choose leaves the patients in this example with extra stress. It means ‘[…] the shifting of the burden and the responsibility for decision making from somebody who knows something to somebody that knows nothing’ (Schwartz, 2007). This not only concerns our health, but our whole identity. ‘We get to reinvent ourselves as often as we like, and that means that every morning we have to decide who we want to be’ (Schwartz, 2007). And if we don’t like who we are, we have to blame ourselves.

Photos: Rogier Alleblas

What causes the individual differences between people with relatively comparable life circumstances that I noticed among my fellow students and peers? According to Schwartz (2004), it’s their way of looking at decisions. ‘Maximizers’ are always looking for the best possible outcome, while ‘satisficers’ are happy with a good enough outcome that satisfies their needs. It’s this second group that is happier. But how is this related to anxiety? Does being a maximizer then lead to depression and anxiety? There is currently not much research indicating that freedom of choice itself leads to severe psychological problems. We shouldn’t forget though that freedom of choice as a dogma forms the basis of the values we hold and the way our society is structured (Schwartz, 2007). It therefore influences how we structure our daily life, and the expectations we have concerning our own decisions and performance. Recent studies among Dutch student populations show that anxiety, stress and depression are increasing (Pieters, 2018). Students interviewed by Folia frequently name the responsibility for the own choices, priorities, performance and future plans as topics that students worry about (Kropman & Vermeer, 2019). The big amount of options we have to choose from is probably just one part of the puzzle that leads to increased anxiety. Besides being anxious at times because of all the options we have to choose from, suffering from anxiety issues can also impact the way we make choices. An interesting article of Hartley and Phelps (2012) shows that anxiety increases the attention for negative options. Additionally, anxious people also tend to interpret ambiguous options negatively. This causes them to become even more anxious, because they feel like they have to choose from negative options only. <<

References

– Botti, S., & Iyengar, S. S. (2006). The dark side of choice: When choice impairs social welfare. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 25(1), 24-38.

– Hartley, C. A., & Phelps, E. A. (2012). Anxiety and decision-making. Biological psychiatry, 72(2), 113-118.

– Iyengar, S. S., & Kamenica, E. (2010). Choice proliferation, simplicity seeking, and asset allocation. Journal of Public Economics, 94(7-8), 530-539.

– Iyengar, S. S., & Lepper, M. R. (2000). When choice is demotivating: Can one desire too much of a good thing?. Journal of personality and social psychology, 79(6), 995-1006.

– Kleinjan, G. (2018). Angst, depressie en zelfmoordgedachten: studenten gaan er aan prestatiedruk onderdoor. Trouw. Retrieved February 17, 2019 from https://www.trouw.nl/samenleving/angst-depressie-en-zelfmoordgedachten-studenten-gaan-er-aan-prestatiedruk-onderdoor~a8336942/.

– Kropman, R. & Vermeer, E. (2019). Zijn gelukscolleges de oplossing voor mentale problemen van studenten? Folia. Retrieved at February 11, 2019 from https://www.folia.nl/actueel/126575/zijn-gelukscolleges-de-oplossing-voor-mentale-problemen-van-studenten/.

– Pieters, J. (2018). More Dutch students struggle with psychological problems, university doctors say. Retrieved February 17, 2019 from https://nltimes.nl/2018/08/14/dutch-students-struggle-psychological-problems-university-doctors-say/.

– Schwartz, B. (2007). Barry Schwartz über Paradoxon der Wahlmöglichkeiten. TED. Retrieved January 25, 2019 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VO6XEQIsCoM/.

– Schwartz, B. (2004). The paradox of choice: Why more is less. New York: Ecco.

– Shiv, B. (2012). Baba Shiv: Manchmal ist es gut, das Ruder aus der Hand zu geben. TED. Retrieved January 25, 2019 from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5tal0NkWW1E/.

– Windesheim, 2017. Onderzoek Studieklimaat, gezondheid en studiesucces 2017. Retrieved February 17, 2019 from http://www.iso.nl/website/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Factsheet_Onderzoek_Studieklimaat_april2018.pdf/.

‘The official dogma of all Western industrial societies is that if we are interested in maximizing the welfare of our citizens, the way to do that is to maximize individual freedom,’ Barry Schwartz, Professor at the Swarthmore College states in his TED Talk Paradox of Choice (2007). ‘The way to maximize freedom is to maximize freedom of choice. The more choice people have, the more freedom they have.’ I recognize this dogma, it reflects the beliefs I hold. I grew up with the mindset that being as free and independent as possible, and therefore being able to freely choose what I want to do and where I want to be, would maximize my chances of being happy. Combined with a good education, a stable job and income, freedom of choice could hypothetically lead to almost everything I want in life: I could live in any place, become whoever I want to be and have the choice of leaving when I felt like moving on.

Yet, if I look around, a lot of successful people I know are unhappy. I know at least ten people my age who come from comparable socio-economic backgrounds and followed a similar curriculum, but are suffering from depression and anxiety issues. When talking to them, they often seem overwhelmed by the sheer amount of decisions and choices they are asked to make. They are confused, they don’t know what they want from life or what they can expect. All their responsibilities seem to weigh heavily on their shoulders. They wander back to decisions they made in the past, considering the possible outcomes of alternative decisions. They are constantly questioning the present and the future, due to an underlying constant doubt of whether they are on the right path. Are they making the most out of their lives? Or is there something to regret, an untaken chance, a missed train?

“Is there something in the nature of choice, that causes students to suffer from anxiety?”

Various newspaper articles published over the last couple of years support this observation of mine: The number of anxiety and depression issues among students is increasing over the last couple of years. An article published in de Volkskrant in 2018 states that an increasing number of students see their doctor because they are struggling with problems as fatigue, concentration problems, panic attacks, anxiety and addiction (Pieters, 2018). Additionally, Dutch newspaper Trouw writes that about half of the students suffers from anxiety and depression (Kleinjan, 2018) and a research on the study climate at Windesheim University of Applied Sciences found 38,9 percent of all students in the school to suffer from light to medium anxiety and depression issues, and 14,4 percent to suffer from strong anxiety and depression issues (Windesheim, 2017).

At the same time, I observe former primary school classmates of mine that never pursued a higher education, because it was always clear that they would take over the farm or bakery of their parents one day. When I visit the little village in the south of Germany where I grew up, they always seem in balance and satisfied with life. I often thought that I could never be happy living their lives because they never lived abroad, often stayed with one of their first partners and settled down very early – in my opinion, without having had the chance to figure out what else they could have done in life. And yet, talking to them, they never complain, and never seem envious of others. The gap between their objectively more limited freedom of choice, and their perceived higher satisfaction makes me curious: is there something in the nature of choice, that causes some students to suffer from anxiety?

Photos: Rogier Alleblas

Comparing my observations and the research findings, it seems to me that total freedom doesn’t necessarily lead to being a happier person. Rather, it seems that those who had less choice are the ones experiencing less regret or doubt. Is there something in the nature of having to make decisions that can be anxiety-inducing rather than happiness-increasing? The marketing professor Baba Shiv thinks so and says the ability to decide do not always makes us happy (Shiv, 2012). In his TED talk he empathizes the importance of ‘giving up the driver’s seat’ every once in a while. According to him, it is doubt that makes decisions unenjoyable. Research conducted by Sheena Iyengar and Mark Lepper (2000) illustrates this issue by showing that participants that have to choose between 24 different types of jam in a gourmet supermarket are less likely to make a choice at all, unlike participants choosing from only three different types of jam in a small supermarket. Despite being overwhelmed and unable to choose in the big supermarket, participants still choose to go to the big supermarket instead of to the small one. This illustrates that our belief in freedom of choice is ‘[…] so deeply embedded in the water supply, that we don’t even dare to question it’ (Schwartz, 2007). ‘If we can, we choose from the biggest number of possible alternatives because we consider the chance higher to find the best possible option there. At the same time, we are less satisfied with the outcome when we get to choose from a great amount of options, even though from an objective standpoint, the outcome is indeed likely to be better than it would have been if we had less options to choose from. Schwartz illustrates this with an autobiographical example of going to a jeans store that in the past offered only one brand that Schwartz used to buy. These days, the choice of jeans is endless, and in the end he leaves the store with the best fitting jeans he ever owned, but less satisfied, because the jeans are good, but not perfect: ‘The reason that everything was better back when everything was worse, is that when everything was worse, it was actually possible for people to have experiences that were a pleasant surprise’ (Schwartz, 2007).

Sheena Iyengar and Emir Kamenica (2010) demonstrate that the mantra ‘less is more’ doesn’t only impact our satisfaction when shopping for groceries or clothing, but can also have drastic impact on important decisions we have to take in life. A clear example of this is retirement savings choices made by half a million employees of the Vanguard Group. As the employees have too many saving plans to choose from, they don’t make a decision at all in the end and will end up without retirement savings in the future. In order for the company to put money away for them, they would have needed to pick a plan. Since they didn’t, the money is slipping through their fingers and if they fail to put money away themselves on a regular basis, they will not have any retirement savings (Iyengar & Kamenica, 2010). So, no choice makes us unfree, but if we have too many options to choose from, we are often unable to make a decision at all, and if we do, choosing leaves us unsatisfied. What is the ‘golden middle’?

“The mantra 'less is more' impacts important decisions we have to make in life”

‘There is no question that some choice is better that none, but it doesn’t logically follow from that that more choice is better than some’, Schwartz (2007) says. If we have no choice at all, we are unhappy, because we realize we are unfree. Therefore, some choice is wishful. If the options exceed the amount of choice we can handle, this doesn’t lead to happiness either. Therefore, some choice, but not none or unlimited choice, is probably the making us the happiest. The reason, Schwartz explains, is that we have to blame ourselves for the outcome if we had all the choices in the world, and in the end the result wasn’t perfect. Freedom of choice sounds like something that is great to have, but it leaves us with a lot of responsibility. This responsibility can be handled if we are making decisions in a field we are familiar with, but daily life decisions we need to make often exceed our knowledge and overtax us. Schwartz uses the example of patient autonomy, a fabulous sounding term that leaves us with the impression that patients have gained the ability to decide what treatment or medicine is best for them, when being provided with the pros and cons of each option by the doctor. The downside of the freedom to choose is that we as decision makers are not actually knowledgeable enough, at all times, to make a good decision, and so having to choose leaves the patients in this example with extra stress. It means ‘[…] the shifting of the burden and the responsibility for decision making from somebody who knows something to somebody that knows nothing’ (Schwartz, 2007). This not only concerns our health, but our whole identity. ‘We get to reinvent ourselves as often as we like, and that means that every morning we have to decide who we want to be’ (Schwartz, 2007). And if we don’t like who we are, we have to blame ourselves.