Presenting to you yet another case of how something sad paradoxically lures us and appeals to us. Philosophers have long been riddled by why we take pleasure in sad art, Greek tragedies and the like. Why sad music though? Why do we actively choose to listen to sad music and enjoy it?

Presenting to you yet another case of how something sad paradoxically lures us and appeals to us. Philosophers have long been riddled by why we take pleasure in sad art, Greek tragedies and the like. Why sad music though? Why do we actively choose to listen to sad music and enjoy it?

Illustration by Nina Kollof

According to me, one of the most fascinating things in life is how we humans derive pleasure from sadness and pain, which my friend and I had the pleasure of writing about earlier (see ‘Paradoxical Pleasures’). This also fascinated the likes of Aristotle, Nietzsche, Hume, Kant, and the rest of the gang! This new piece, though, zooms in on one more recent account that proposes why we enjoy sad music in particular. If you’ve found yourself in your very own movie scene – playing sad beats to accompany your recent sorrows and sitting by your window as the rain pours on – have you ever wondered why?

In the case of sad music, a few suggestions have been made as to why music evokes such emotions in us. One of these theories is that negative emotions arise from learned associations. An example of this in the Western context is that the association between the minor-scale and sad or grievous contexts is learned through classical conditioning (Valentine, 1913/1914 as cited in Huron, 2011). On the other hand, a proposed psychological cause of sad music evoking negative emotions is cognitive rumination, delving deep into negative thoughts, possibly provoked by certain acoustic properties and associations. In this article, I will zoom into one of the biological mechanisms that could be at play. In the spirit of acknowledging individual differences, the core tenet of Psychology really, I will note early on that not everyone enjoys sad music (Huron & Vuoskoski, 2020), but it’s interesting to see why this paradox exists and also attempt to account for these individual differences.

“Sad music leads to the release of (psychic) tears, and due to the high concentration of prolactin in these tears, it leads to a feeling of comfort and calmness.”

Studies that looked at ‘sad feelings’ usually used self-report measures, which are based on introspection, and these have been known to be quite inaccurate (Graves, 2010; Lehrer, 2009 as cited in Huron, 2011). Having said this, one of the proposed suggestions for the cause of negative emotions evoked by sad music is quite interesting, since it looks at a potential physical manifestation of sadness. The most common physical sign of sadness or grief is tears, lacrimation (Huron, 2011). Huron (2011) notes that there are two types of tears – psychic and irritant tears. Irritant tears are those caused by objects in the environment, such as onions or dust, but psychic tears are those caused by emotional intensity. In particular, psychic tears are those that arise from intense feelings (specifically pain) (Huron, 2011). It was found that chemically, the one thing that differentiates psychic tears and irritant tears is that psychic tears are marked by a high level of prolactin, a peptide hormone (Frey 1985 as cited in Huron, 2011). Prolactin is secreted as a response to stressful conditions, but the changes in prolactin levels are also noticed when consolation and comfort is received (Ladinig, Brooks, Hansen, Horn & Huron, 2019). Consequently, the effects of prolactin include being in a calm and feel-good state of mind. This implies that a higher concentration of prolactin in psychic tears, produced when emotional pain or intense sadness is experienced, should lead to a positive and calm state of mind upon hearing sad music. Sad music thus leads to the release of (psychic) tears due to the emotional intensity it harbours, and due to the high concentration of prolactin in these tears, it leads to a feeling of comfort and calmness. Huron (2011) suggests that prolactin might have a homeostatic function and helps control the emotional and physical pain; this is known at the homeostatic theory. However, Huron’s theory, when tested, did not reveal positive results in his favour (Ladinig et al., 2019). Past studies that looked at the changes in hormones in the context of music did not yield very clear results on how prolactin concentration in the body changes.

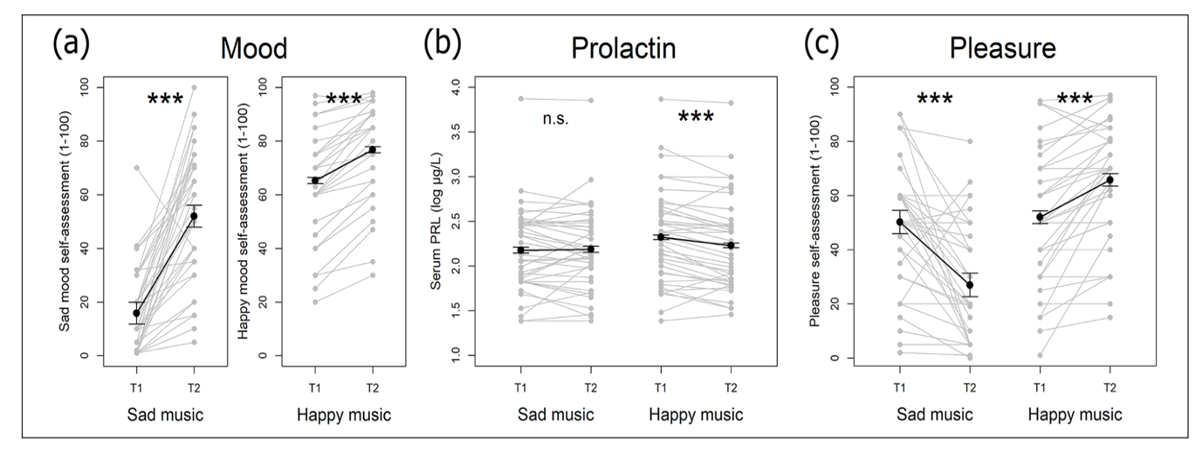

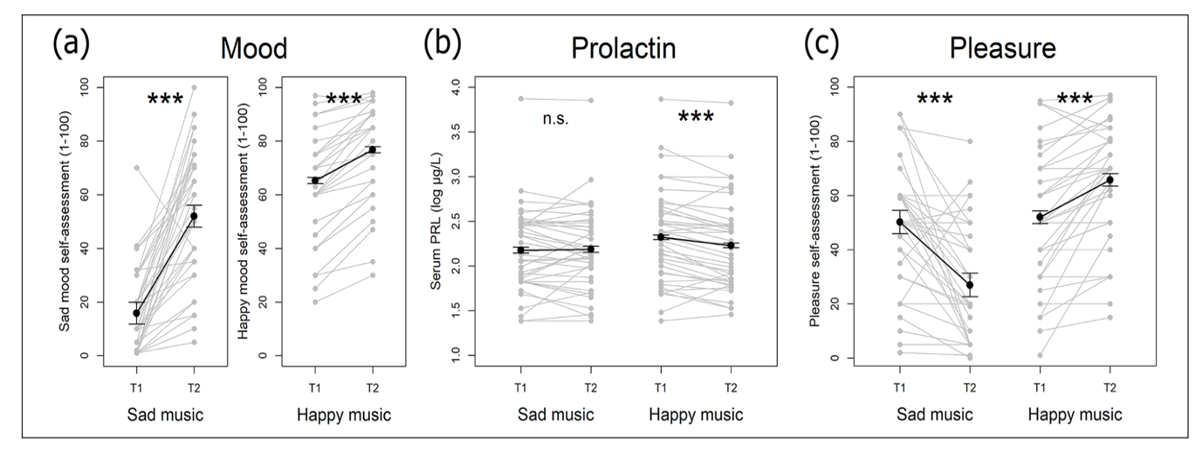

Ladinig and colleagues (2019) conducted an experiment to empirically test Huron’s theory. They observed changes in prolactin levels in sad-music lovers and haters upon being exposed to sad music and happy music. In addition to prolactin levels, they also measured mood and pleasure levels. Most importantly, though, in the sad music condition there was no significant change in the concentration of prolactin (see Figure 1; Serum PRL = Serum Prolactin). Figure 1 shows individual data points, but on a whole, sad music does not seem to please most people and also results in an increase in sadness (mood).

Figure 1. Adapted from Ladinig, O., Brooks, C., Hansen, N. C., Horn, K., & Huron, D. (2019). Enjoying sad music: A test of the prolactin theory. Musicae Scientiae, 25(4), 429–448.

Personally, I quite liked Huron’s proposition, and if it stood the empirical test, it would be rather neat indeed, but sadly (or not so sadly) science does not work this way. Ladinig and colleagues point out certain confounds that could have resulted in the non-significant results. Firstly, some researchers question the ‘sadness’ construct that is evoked by sad music – they contend that actual sadness is different from the sadness caused by art forms. A persisting issue with hormonal studies, though, is also that dopamine, a hormone associated with reward and pleasure, is known to inhibit the release of prolactin. While we would expect to see an increase in dopamine, as result of pleasure, and prolactin, in accordance with Huron’s theory, it would be complex to expect this in research due to this compounded relationship between dopamine and prolactin (Eerola et al., 2021).

While this is just one theory, there appears to be no general consensus on this matter in the field, since the current ones sometimes clash with one another and in general not much research has been done in this area. However, akin to what has been suggested with regards to why we enjoy other sad art (films, painting, plays, etc.), we feel a sense of pleasure because we don’t actually experience the actual threat associated with this sadness (Sachs, Damasio & Habibi, 2015). While sad music can yield pleasure for some, it is not the case for all and this does depend on individual differences, including personality traits, current mood and social contexts (Sachs, Damasio & Habibi, 2015). All in all, given the lack of consensus on this matter, I reckon this paradox will continue haunting us as it did with the chain of old philosophers from back in the day. <<

References

-Eerola, T., Vuoskoski, J. K., Kautiainen, H., Peltola, H., Putkinen, V., & Schäfer, K. (2021). Being moved by listening to unfamiliar sad music induces reward‐related hormonal changes in empathic listeners. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1502(1), 121–131. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.14660

-Huron, D. (2011). Why is sad music pleasurable? A possible role for prolactin. Musicae Scientiae, 15(2), 146–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1029864911401171

-Huron, D., & Vuoskoski, J. K. (2020). On the Enjoyment of Sad Music: Pleasurable Compassion Theory and the Role of Trait Empathy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01060

-Ladinig, O., Brooks, C., Hansen, N. C., Horn, K., & Huron, D. (2019). Enjoying sad music: A test of the prolactin theory. Musicae Scientiae, 25(4), 429–448. https://doi.org/10.1177/1029864919890900

-Sachs, M. E., Damasio, A., & Habibi, A. (2015). The pleasures of sad music: a systematic review. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00404

According to me, one of the most fascinating things in life is how we humans derive pleasure from sadness and pain, which my friend and I had the pleasure of writing about earlier (see ‘Paradoxical Pleasures’). This also fascinated the likes of Aristotle, Nietzsche, Hume, Kant, and the rest of the gang! This new piece, though, zooms in on one more recent account that proposes why we enjoy sad music in particular. If you’ve found yourself in your very own movie scene – playing sad beats to accompany your recent sorrows and sitting by your window as the rain pours on – have you ever wondered why?

In the case of sad music, a few suggestions have been made as to why music evokes such emotions in us. One of these theories is that negative emotions arise from learned associations. An example of this in the Western context is that the association between the minor-scale and sad or grievous contexts is learned through classical conditioning (Valentine, 1913/1914 as cited in Huron, 2011). On the other hand, a proposed psychological cause of sad music evoking negative emotions is cognitive rumination, delving deep into negative thoughts, possibly provoked by certain acoustic properties and associations. In this article, I will zoom into one of the biological mechanisms that could be at play. In the spirit of acknowledging individual differences, the core tenet of Psychology really, I will note early on that not everyone enjoys sad music (Huron & Vuoskoski, 2020), but it’s interesting to see why this paradox exists and also attempt to account for these individual differences.

“Sad music leads to the release of (psychic) tears, and due to the high concentration of prolactin in these tears, it leads to a feeling of comfort and calmness.”

Studies that looked at ‘sad feelings’ usually used self-report measures, which are based on introspection, and these have been known to be quite inaccurate (Graves, 2010; Lehrer, 2009 as cited in Huron, 2011). Having said this, one of the proposed suggestions for the cause of negative emotions evoked by sad music is quite interesting, since it looks at a potential physical manifestation of sadness. The most common physical sign of sadness or grief is tears, lacrimation (Huron, 2011). Huron (2011) notes that there are two types of tears – psychic and irritant tears. Irritant tears are those caused by objects in the environment, such as onions or dust, but psychic tears are those caused by emotional intensity. In particular, psychic tears are those that arise from intense feelings (specifically pain) (Huron, 2011). It was found that chemically, the one thing that differentiates psychic tears and irritant tears is that psychic tears are marked by a high level of prolactin, a peptide hormone (Frey 1985 as cited in Huron, 2011). Prolactin is secreted as a response to stressful conditions, but the changes in prolactin levels are also noticed when consolation and comfort is received (Ladinig, Brooks, Hansen, Horn & Huron, 2019). Consequently, the effects of prolactin include being in a calm and feel-good state of mind. This implies that a higher concentration of prolactin in psychic tears, produced when emotional pain or intense sadness is experienced, should lead to a positive and calm state of mind upon hearing sad music. Sad music thus leads to the release of (psychic) tears due to the emotional intensity it harbours, and due to the high concentration of prolactin in these tears, it leads to a feeling of comfort and calmness. Huron (2011) suggests that prolactin might have a homeostatic function and helps control the emotional and physical pain; this is known at the homeostatic theory. However, Huron’s theory, when tested, did not reveal positive results in his favour (Ladinig et al., 2019). Past studies that looked at the changes in hormones in the context of music did not yield very clear results on how prolactin concentration in the body changes.

Ladinig and colleagues (2019) conducted an experiment to empirically test Huron’s theory. They observed changes in prolactin levels in sad-music lovers and haters upon being exposed to sad music and happy music. In addition to prolactin levels, they also measured mood and pleasure levels. Most importantly, though, in the sad music condition there was no significant change in the concentration of prolactin (see Figure 1; Serum PRL = Serum Prolactin). Figure 1 shows individual data points, but on a whole, sad music does not seem to please most people and also results in an increase in sadness (mood).

Figure 1. Adapted from Ladinig, O., Brooks, C., Hansen, N. C., Horn, K., & Huron, D. (2019). Enjoying sad music: A test of the prolactin theory. Musicae Scientiae, 25(4), 429–448.

Personally, I quite liked Huron’s proposition, and if it stood the empirical test, it would be rather neat indeed, but sadly (or not so sadly) science does not work this way. Ladinig and colleagues point out certain confounds that could have resulted in the non-significant results. Firstly, some researchers question the ‘sadness’ construct that is evoked by sad music – they contend that actual sadness is different from the sadness caused by art forms. A persisting issue with hormonal studies, though, is also that dopamine, a hormone associated with reward and pleasure, is known to inhibit the release of prolactin. While we would expect to see an increase in dopamine, as result of pleasure, and prolactin, in accordance with Huron’s theory, it would be complex to expect this in research due to this compounded relationship between dopamine and prolactin (Eerola et al., 2021).

While this is just one theory, there appears to be no general consensus on this matter in the field, since the current ones sometimes clash with one another and in general not much research has been done in this area. However, akin to what has been suggested with regards to why we enjoy other sad art (films, painting, plays, etc.), we feel a sense of pleasure because we don’t actually experience the actual threat associated with this sadness (Sachs, Damasio & Habibi, 2015). While sad music can yield pleasure for some, it is not the case for all and this does depend on individual differences, including personality traits, current mood and social contexts (Sachs, Damasio & Habibi, 2015). All in all, given the lack of consensus on this matter, I reckon this paradox will continue haunting us as it did with the chain of old philosophers from back in the day.<<