They build the air you breathe; they shape the soil beneath your feet; they unlock the nutrients you eat; they enrich the water you drink. They are the beginning and the end, conductors of the wheel of life and decay. They are all around us, omnipresent, in me and in you. They are not deities – they are microbes.

They build the air you breathe; they shape the soil beneath your feet; they unlock the nutrients you eat; they enrich the water you drink. They are the beginning and the end, conductors of the wheel of life and decay. They are all around us, omnipresent, in me and in you. They are not deities – they are microbes.

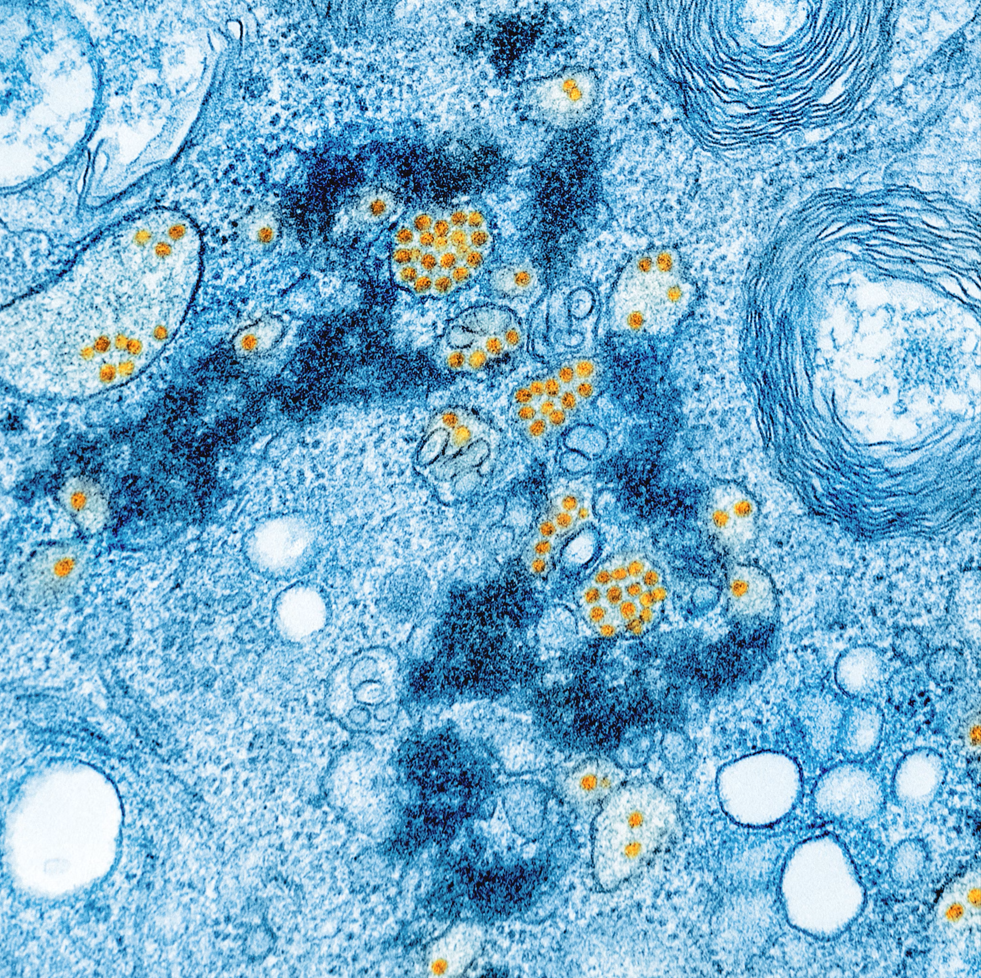

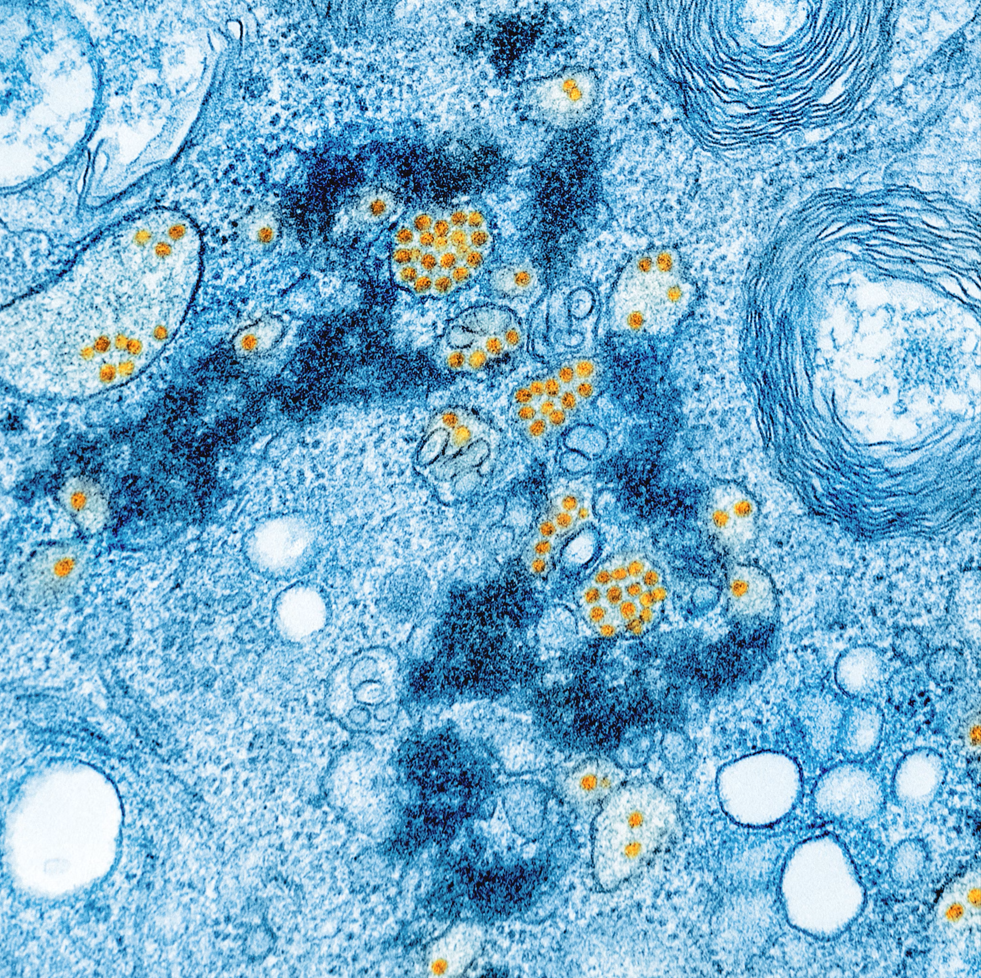

Photo by NIAID

Microorganisms emerged from an Earth enveloped by toxic fumes about 4 billion years ago. Around 2.7 billion years ago, these unseen pioneers said: “let there be oxygen!” And there was oxygen – if said was the equivalent of a biochemical process akin to photosynthesis. They became the architects who laid the foundations for all complex life, including our own (Chimileski & Kolter, 2017). However, their involvement does not stop at the foundations: from the depths of our gut to the surface of our skin, microbes form intricate networks that influence our physiology in ways we are only beginning to grasp. Ongoing research is unveiling their profound role in regulating mood, behavior and even susceptibility to psychiatric disorders.

“I am master of my fate; I am the captain of my soul”– William Ernest Henley You probably think of yourself as human. However, what this constitutes is called into question if one considers that the number of bacterial cells exceeds those of human ones (38 trillion against 30 trillion) . The ‘I’ becomes a ‘We’, and the body the host of a civilization, one that has its capital in the gut, concentrating more than 95% of its population (Sender, et al., 2016). We may still be captains, but within us, a microbial crew also steers our course.

Hidden in the confines of our body, the gut remained a mystery for most of history. That changed in 1822, when a musket shot pierced Alexis St. Martin’s abdomen. The young French-Canadian merchant did not die, but was left with a hole in his stomach. William Beaumont, a U.S Army surgeon, took the unprecedented opportunity to delve into the workings of digestion. By inserting food directly through the opening in St. Martin’ stomach he opened a literal window into the intricacies of digestion. Though ethically controversial, Beaumont’s research led him to be considered the father of gastroenterology and offered the earliest evidence of emotional and stress implications on digestion, providing the first hint of a connection between the gut and the brain. (Yong, 2016)

“The ‘I’ becomes a ‘We’, and the body the host of a civilization, one that has its capital in the gut.”

Phrases like “gut feeling” and “trust your gut” are more than just figures of speech – they echo our intuitive grasp of the relationship between emotions and the stomach. Previously, it was assumed that digestive issues present in common psychological disorders, such as anxiety and depression, were simply symptoms of the condition. However, recent discoveries indicate that the relationship also works the other way around, with gut health influencing our emotional states as well. This interplay is rooted in the gut-brain axis, a bidirectional communication pathway between the central nervous system and the gastrointestinal tract, which itself houses hundreds of millions of neurons (Talley, 2016). While it does not think in the traditional sense, it is often referred to as our “second brain”.

This relationship is best understood as a trio: the microbiota-gut-brain axis. The gut microbiota – i.e., the community of microorganisms inside the gut – communicates with the brain via the vagus nerve, the enteric nervous system (part of the autonomic nervous system) and the neuroendocrine system. These pathways of influence are marked by the production of neuroactive substances, metabolites, and hormones which enable modulation of brain chemistry, immunity, and circulation (Loh, et al., 2024). If the gut is the second brain, its microorganisms are the central executive.

The biological importance of the gut microbiome is evident from the moment of birth, when the intestine becomes home to a unique microbial community through exposure to the mother’s vaginal microflora. This first colonization sets the stage for a microbiome–the combined genetic material of microorganisms–that stabilizes by the age of 2 to 3. This coincides with critical periods of neural and immune system development, both of which are actively shaped by these microbes (Rutsch, et al., 2020).

The influence of these microbes on the brain is striking. Rutsch et al. (2020) showed that germ-free mice exhibit neurological changes, including heightened stress, impaired social behavior, reduced anxiety-like responses, and increased hyperactivity. Remarkably, restoring their microbiota diversity reverses these effects, underscoring the microbiota’s fundamental role in brain function and behavior.

In his book I contain Multitudes, Ed Yong (2016) describes the gut microbiota as an ecosystem, where the biodiversity of microorganisms ensures a symbiotic relationship with their host (the human body). Bacteria aid digestion, regulate the immune system, and influence cognition. In return, we provide them a stable environment and the nutrients they need to survive. However, factors like poor diet, stress, excessive antibiotic use, aging, and sleep deprivation can act as the pollutants that, by contaminating the microflora, disrupt its balance – a state known as dysbiosis.

The symbiotic relationship with our microorganisms is contextual: depending on environmental factors, location within the body and even combination with other microbes, former allies can become opportunistic threats (Yong, 2016). To prevent harmful bacterial translocation into the bloodstream, the gastrointestinal tract is lined with a mucus barrier. Ironically, however, the microbiota itself regulates this defense (Paone & Cani, 2020). In dysbiosis, bacteria that degrade the barrier proliferate, while those that reinforce it get depleted. This ultimately leads to bacterial encroachment, triggering inflammation, which is implicated in conditions like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, multiple sclerosis and some mood disorders (Rutsch, et al., 2020; Loh, et al., 2024). In dysbiosis, our relationship with bacteria is the antithesis of symbiosis (Yong, 2016).

“If the gut is the second brain, its microorganisms are the central executive.”

Growing awareness of the gut microbiota’s role in health has spurred the development of microbiome-based therapies, comprising of prebiotics (compounds that promote bacterial growth), probiotics (live bacteria), and Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT), a treatment where a healthy donor’s stool is transferred into the gastrointestinal tract of a patient to restore their microbial balance – perhaps the only case where handling someone else’s sh*t can fix your own.

Preclinical studies suggest these interventions can restore the microbial diversity and alleviate associated health conditions, yet their clinical application remains limited. FMT, for instance, lacks a standardized protocol, and because the transfer of bacteria is indiscriminate, it may also introduce harmful microbes. Meanwhile, the effectiveness of probiotics and prebiotics varies with individual differences in microbiota composition. Given these challenges, more research is needed before microbiome-based therapies become mainstream. (Loh, et al., 2024).

For now, the time-honored advice of a healthy lifestyle – staying active, sleeping well, and eating a balanced diet – also benefits gut health. In particular, research suggests that a fiber-rich diet fosters microbial diversity and mitigates inflammation as well as the accompanying ailments. Conversely, a low-fiber, Western-style diet fuels dysbiosis and its detrimental effects on physical and mental health (Bourassa et al., 2016; Wilson, et al., 2020).

“When you choose your meals, you are also choosing which bacteria get fed, and which get an advantage over their peers” – (Yong, 2016, p.75)

In essence, our dietary choices shape the microbial communities within us, which in turn influence our overall well-being, reinforcing the adage “you are what you eat”. So yes – this is propaganda for you to eat your veggies.

To avoid the trap of essentialism, it is important to note that, despite the sensational title, bacteria are not omnipotent. Much research remains preclinical, and we would do well to remember we are complex beings; subjects of internal and external elements that, in both a greatly coordinated and erratic way, orchestrate our position on the spectrum between stability and instability, health and disease, sadness and joy. Bacteria are just one of these elements, and we are still the directors of the band. <<

References

- Bourassa, M. W., Alim, I., Bultman, S. J., & Ratan, R. R. (2016). Butyrate, neuroepigenetics and the gut microbiome: Can a high fiber diet improve brain health? Neuroscience Letters, 625, 53-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2016.02.009

- Chimileski, S., & Kolter, R. (2017). Microbes gave us life. STAT. Retrieved from https://www.statnews.com/2017/12/21/microbes-human-life/#:~:text=Heat%20fluctuations%20and%20turbulence%20in,the%20first%20life%20on%20Earth.

- Loh, J. S., Mak, W. Q., Tan, S. K., Xin Ng, C., Chan, H. H., Yeow, H. S., & … (2024). Microbiota–gut–brain axis and its therapeutic applications in neurodegenerative diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 9(32). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-024-01743-1

- Paone, P., & Cani, P. D. (2020). Mucus barrier, mucins and gut microbiota: the expected slimy partners? Gut, 69(12), 2232-2243. Retrieved from 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322260

- Rutsch, A., Kantsjö, J. B., & Ronchi, F. (2020). The Gut-Brain Axis: How microbiota and host inflammasome influence brain physiology and pathology. Frontiers in Immunology, 11.https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.604179

- Sender, R., Fuchs, S., & Milo, R. (2016). Revised estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body. PLOS Biology, 14(8). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002533

- Talley, N. (2016). Stomach and mood disorders: how your gut may be playing with your mind. Retrieved from The Conversation: https://theconversation.com/stomach-and-mood-disorders-how-your-gut-may-be-playing-with-your-mind-50847

- Wilson, A., Koller, K., Ramaboli, M., Nesengani, T., Ocvirk, S., & … (2020). Diet and the Human Gut Microbiome: An International Review. Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 65, 723-740. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-020-06112-w

- Yong, E. (2016). I contain multitudes: The microbes within us and a grander view of Life. Harper Collins Publishers.

Microorganisms emerged from an Earth enveloped by toxic fumes about 4 billion years ago. Around 2.7 billion years ago, these unseen pioneers said: “let there be oxygen!” And there was oxygen – if said was the equivalent of a biochemical process akin to photosynthesis. They became the architects who laid the foundations for all complex life, including our own (Chimileski & Kolter, 2017). However, their involvement does not stop at the foundations: from the depths of our gut to the surface of our skin, microbes form intricate networks that influence our physiology in ways we are only beginning to grasp. Ongoing research is unveiling their profound role in regulating mood, behavior and even susceptibility to psychiatric disorders.

“I am master of my fate; I am the captain of my soul”– William Ernest Henley You probably think of yourself as human. However, what this constitutes is called into question if one considers that the number of bacterial cells exceeds those of human ones (38 trillion against 30 trillion) . The ‘I’ becomes a ‘We’, and the body the host of a civilization, one that has its capital in the gut, concentrating more than 95% of its population (Sender, et al., 2016). We may still be captains, but within us, a microbial crew also steers our course.

Hidden in the confines of our body, the gut remained a mystery for most of history. That changed in 1822, when a musket shot pierced Alexis St. Martin’s abdomen. The young French-Canadian merchant did not die, but was left with a hole in his stomach. William Beaumont, a U.S Army surgeon, took the unprecedented opportunity to delve into the workings of digestion. By inserting food directly through the opening in St. Martin’ stomach he opened a literal window into the intricacies of digestion. Though ethically controversial, Beaumont’s research led him to be considered the father of gastroenterology and offered the earliest evidence of emotional and stress implications on digestion, providing the first hint of a connection between the gut and the brain. (Yong, 2016)

“The ‘I’ becomes a ‘We’, and the body the host of a civilization, one that has its capital in the gut.”

Phrases like “gut feeling” and “trust your gut” are more than just figures of speech – they echo our intuitive grasp of the relationship between emotions and the stomach. Previously, it was assumed that digestive issues present in common psychological disorders, such as anxiety and depression, were simply symptoms of the condition. However, recent discoveries indicate that the relationship also works the other way around, with gut health influencing our emotional states as well. This interplay is rooted in the gut-brain axis, a bidirectional communication pathway between the central nervous system and the gastrointestinal tract, which itself houses hundreds of millions of neurons (Talley, 2016). While it does not think in the traditional sense, it is often referred to as our “second brain”.

This relationship is best understood as a trio: the microbiota-gut-brain axis. The gut microbiota – i.e., the community of microorganisms inside the gut – communicates with the brain via the vagus nerve, the enteric nervous system (part of the autonomic nervous system) and the neuroendocrine system. These pathways of influence are marked by the production of neuroactive substances, metabolites, and hormones which enable modulation of brain chemistry, immunity, and circulation (Loh, et al., 2024). If the gut is the second brain, its microorganisms are the central executive.

The biological importance of the gut microbiome is evident from the moment of birth, when the intestine becomes home to a unique microbial community through exposure to the mother’s vaginal microflora. This first colonization sets the stage for a microbiome–the combined genetic material of microorganisms–that stabilizes by the age of 2 to 3. This coincides with critical periods of neural and immune system development, both of which are actively shaped by these microbes (Rutsch, et al., 2020).

The influence of these microbes on the brain is striking. Rutsch et al. (2020) showed that germ-free mice exhibit neurological changes, including heightened stress, impaired social behavior, reduced anxiety-like responses, and increased hyperactivity. Remarkably, restoring their microbiota diversity reverses these effects, underscoring the microbiota’s fundamental role in brain function and behavior.

In his book I contain Multitudes, Ed Yong (2016) describes the gut microbiota as an ecosystem, where the biodiversity of microorganisms ensures a symbiotic relationship with their host (the human body). Bacteria aid digestion, regulate the immune system, and influence cognition. In return, we provide them a stable environment and the nutrients they need to survive. However, factors like poor diet, stress, excessive antibiotic use, aging, and sleep deprivation can act as the pollutants that, by contaminating the microflora, disrupt its balance – a state known as dysbiosis.

The symbiotic relationship with our microorganisms is contextual: depending on environmental factors, location within the body and even combination with other microbes, former allies can become opportunistic threats (Yong, 2016). To prevent harmful bacterial translocation into the bloodstream, the gastrointestinal tract is lined with a mucus barrier. Ironically, however, the microbiota itself regulates this defense (Paone & Cani, 2020). In dysbiosis, bacteria that degrade the barrier proliferate, while those that reinforce it get depleted. This ultimately leads to bacterial encroachment, triggering inflammation, which is implicated in conditions like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, multiple sclerosis and some mood disorders (Rutsch, et al., 2020; Loh, et al., 2024). In dysbiosis, our relationship with bacteria is the antithesis of symbiosis (Yong, 2016).

“If the gut is the second brain, its microorganisms are the central executive.”

Growing awareness of the gut microbiota’s role in health has spurred the development of microbiome-based therapies, comprising of prebiotics (compounds that promote bacterial growth), probiotics (live bacteria), and Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT), a treatment where a healthy donor’s stool is transferred into the gastrointestinal tract of a patient to restore their microbial balance – perhaps the only case where handling someone else’s sh*t can fix your own.

Preclinical studies suggest these interventions can restore the microbial diversity and alleviate associated health conditions, yet their clinical application remains limited. FMT, for instance, lacks a standardized protocol, and because the transfer of bacteria is indiscriminate, it may also introduce harmful microbes. Meanwhile, the effectiveness of probiotics and prebiotics varies with individual differences in microbiota composition. Given these challenges, more research is needed before microbiome-based therapies become mainstream. (Loh, et al., 2024).

For now, the time-honored advice of a healthy lifestyle – staying active, sleeping well, and eating a balanced diet – also benefits gut health. In particular, research suggests that a fiber-rich diet fosters microbial diversity and mitigates inflammation as well as the accompanying ailments. Conversely, a low-fiber, Western-style diet fuels dysbiosis and its detrimental effects on physical and mental health (Bourassa et al., 2016; Wilson, et al., 2020).

“When you choose your meals, you are also choosing which bacteria get fed, and which get an advantage over their peers” – (Yong, 2016, p.75)

In essence, our dietary choices shape the microbial communities within us, which in turn influence our overall well-being, reinforcing the adage “you are what you eat”. So yes – this is propaganda for you to eat your veggies.

To avoid the trap of essentialism, it is important to note that, despite the sensational title, bacteria are not omnipotent. Much research remains preclinical, and we would do well to remember we are complex beings; subjects of internal and external elements that, in both a greatly coordinated and erratic way, orchestrate our position on the spectrum between stability and instability, health and disease, sadness and joy. Bacteria are just one of these elements, and we are still the directors of the band. <<

References

- Bourassa, M. W., Alim, I., Bultman, S. J., & Ratan, R. R. (2016). Butyrate, neuroepigenetics and the gut microbiome: Can a high fiber diet improve brain health? Neuroscience Letters, 625, 53-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2016.02.009

- Chimileski, S., & Kolter, R. (2017). Microbes gave us life. STAT. Retrieved from https://www.statnews.com/2017/12/21/microbes-human-life/#:~:text=Heat%20fluctuations%20and%20turbulence%20in,the%20first%20life%20on%20Earth.

- Loh, J. S., Mak, W. Q., Tan, S. K., Xin Ng, C., Chan, H. H., Yeow, H. S., & … (2024). Microbiota–gut–brain axis and its therapeutic applications in neurodegenerative diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 9(32). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-024-01743-1

- Paone, P., & Cani, P. D. (2020). Mucus barrier, mucins and gut microbiota: the expected slimy partners? Gut, 69(12), 2232-2243. Retrieved from 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322260

- Rutsch, A., Kantsjö, J. B., & Ronchi, F. (2020). The Gut-Brain Axis: How microbiota and host inflammasome influence brain physiology and pathology. Frontiers in Immunology, 11.https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.604179

- Sender, R., Fuchs, S., & Milo, R. (2016). Revised estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body. PLOS Biology, 14(8). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.1002533

- Talley, N. (2016). Stomach and mood disorders: how your gut may be playing with your mind. Retrieved from The Conversation: https://theconversation.com/stomach-and-mood-disorders-how-your-gut-may-be-playing-with-your-mind-50847

- Wilson, A., Koller, K., Ramaboli, M., Nesengani, T., Ocvirk, S., & … (2020). Diet and the Human Gut Microbiome: An International Review. Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 65, 723-740. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-020-06112-w

- Yong, E. (2016). I contain multitudes: The microbes within us and a grander view of Life. Harper Collins Publishers.