According to the translator, art critic, and philosopher Walter Benjamin, to critique a work of art is to become its partial co-creator. By reflecting on an artwork, we are reflecting on ourselves and on our society. If that is the case, what could a book on the life and ideas of Walter Benjamin and three of his philosophical contemporaries teach us? Or, alternatively, the review of such a book?

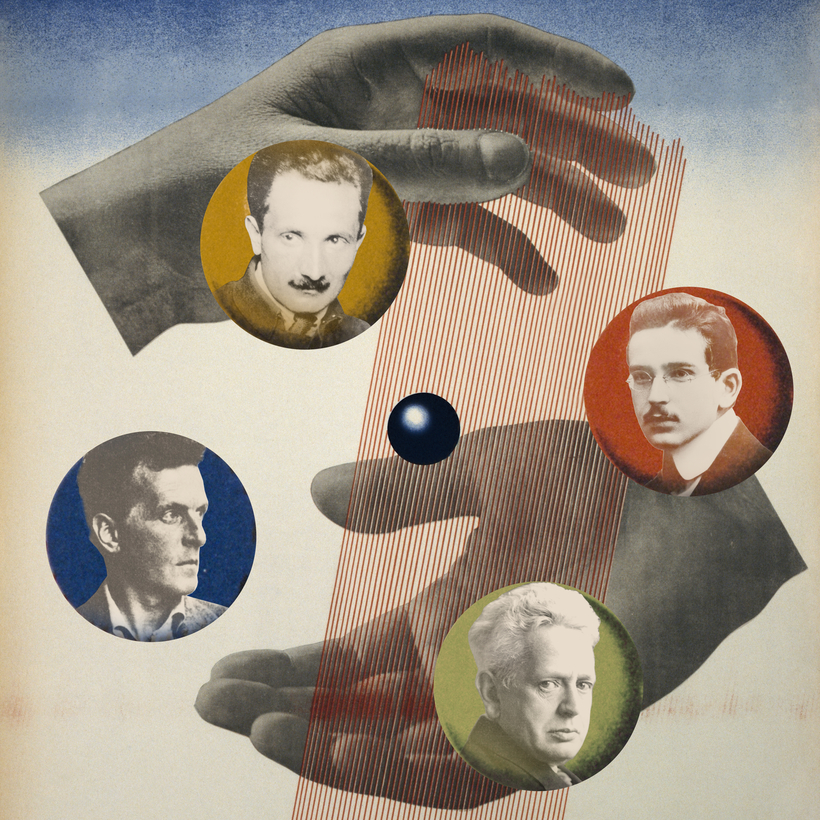

While reading this book, you may face many such questions. In Time of the Magicians, Wolfram Eilenberger takes you back to the post-First World War decade of 1919-1929, and introduces you to some of the most notable philosophers of that era. Part biography and part philosophy handbook, Time of the Magicians follows the lives and ideas of the philosophers Ludwig Wittgenstein, Ernst Cassirer, Martin Heidegger, and Walter Benjamin.

Eilenberger is a skilled storyteller, who manages to convey some of the excitement that philosophers might have felt during this prolific era in philosophy. At the same time, while reading the book, it becomes clear that this era wasn’t exciting at all, but in fact rather horrid – especially when you were a philosopher trying to get by in a war-wrecked and impoverished Germany, frequently at the brinks of starvation and civil war.

One thing Eilenberger clearly is not, is feminist. When the author describes how Heidegger began a relationship with his then-student Hannah Arendt, who would later become a notable philosopher of her own accord, Eilenberger focuses on the circumstances of their extramarital affair. He does not elaborate on Hannah Arendt’s philosophical ideas, but describes them as a mere reaction to Heidegger’s ideas, rather than evaluating them on their own merits.

Time of the Magicians focuses on the first decade of the period between the First and Second World War. During this period, antisemitism was on the rise. Heidegger was an antisemite who would join the NSDAP (the Nazi party) in the 1930s, whereas the other philosophers would be forced into exile for being considered Jewish by the Nazis. The Warburg Library – a library held dearly by Cassirer – would move to London in its entirety to avoid the Nazi book burnings (Warburg, 1953). During their exile, both Ernst Cassirer and Hannah Arendt would write books about the rise of totalitarianism. A detailed discussion on how Nazism influenced the lives and ideas of these four (or five) philosophers may be beyond the scope of this book, but to focus solely on the decade 1919-1929 seems somewhat naive in the light of what followed. A mere four years later, in 1933, the Nazis would come to power in Germany – which would eventually lead to the Second World War and the Holocaust.

Although the author has a neutral tone in his writing, it is sometimes hard to distinguish between the philosophers’ ideas and Eilenberger’s interpretation of them. The author could be more clear about this.

Eilenberger holds his readers in high regard – possibly a little too highly. When Eilenberger writes about the friendship between Wittgenstein and philosopher Bertrand Russell, it would be interesting to learn more about the ideas of Russell. But if you want to know more about Russell’s work – or the works of Kant or Husserl, who influenced these philosophers, for that matter – you will have to look them up yourself. When Eilenberger comments on a rather obscure philosophical point: ‘a child could have understood it,’ I wonder if I should perhaps ask a child to explain it to me, for Eilenberger doesn’t. Another thing he doesn’t explain thoroughly is what the parallels and contrasts are between the theories of these philosophers. There are clearly common themes in their philosophy, but it is up to the reader to discern these themes and to understand how the philosophers’ ideas complement and contradict each other. This can give you the feeling that you are reading four intertwined biographies, rather than one story as a whole.

In Time of the Magicians, Eilenberger manages to explain some very complicated philosophical ideas in an almost-comprehensible manner – not a small feat considering the complexity of the philosophical theories he writes about. Nevertheless, if you are looking for a light read, or a primer in philosophy, this might not be the book for you. If you wish to know more about the ideas of these four philosophers, however, already have some background knowledge in philosophy, and plenty of time to read the book slowly and carefully, one page at a time, you may find Time of the Magicians an interesting read.

Available at your local book store or online, starting from €17,89. A Dutch translation is also available: Tijdperk van de Tovenaars, starting from €34,99.

References

– Warburg, E. M. (1953). The Warburg Institute annual report 1952-1953. Retrieved 15 december 2021 from: https://warburg.sas.ac.uk/about-us/history-warburg-institute/transfer-institute

According to the translator, art critic, and philosopher Walter Benjamin, to critique a work of art is to become its partial co-creator. By reflecting on an artwork, we are reflecting on ourselves and on our society. If that is the case, what could a book on the life and ideas of Walter Benjamin and three of his philosophical contemporaries teach us? Or, alternatively, the review of such a book?

While reading this book, you may face many such questions. In Time of the Magicians, Wolfram Eilenberger takes you back to the post-First World War decade of 1919-1929, and introduces you to some of the most notable philosophers of that era. Part biography and part philosophy handbook, Time of the Magicians follows the lives and ideas of the philosophers Ludwig Wittgenstein, Ernst Cassirer, Martin Heidegger, and Walter Benjamin.

Eilenberger is a skilled storyteller, who manages to convey some of the excitement that philosophers might have felt during this prolific era in philosophy. At the same time, while reading the book, it becomes clear that this era wasn’t exciting at all, but in fact rather horrid – especially when you were a philosopher trying to get by in a war-wrecked and impoverished Germany, frequently at the brinks of starvation and civil war.

One thing Eilenberger clearly is not, is feminist. When the author describes how Heidegger began a relationship with his then-student Hannah Arendt, who would later become a notable philosopher of her own accord, Eilenberger focuses on the circumstances of their extramarital affair. He does not elaborate on Hannah Arendt’s philosophical ideas, but describes them as a mere reaction to Heidegger’s ideas, rather than evaluating them on their own merits.

Time of the Magicians focuses on the first decade of the period between the First and Second World War. During this period, antisemitism was on the rise. Heidegger was an antisemite who would join the NSDAP (the Nazi party) in the 1930s, whereas the other philosophers would be forced into exile for being considered Jewish by the Nazis. The Warburg Library – a library held dearly by Cassirer – would move to London in its entirety to avoid the Nazi book burnings (Warburg, 1953). During their exile, both Ernst Cassirer and Hannah Arendt would write books about the rise of totalitarianism. A detailed discussion on how Nazism influenced the lives and ideas of these four (or five) philosophers may be beyond the scope of this book, but to focus solely on the decade 1919-1929 seems somewhat naive in the light of what followed. A mere four years later, in 1933, the Nazis would come to power in Germany – which would eventually lead to the Second World War and the Holocaust.

Although the author has a neutral tone in his writing, it is sometimes hard to distinguish between the philosophers’ ideas and Eilenberger’s interpretation of them. The author could be more clear about this.

Eilenberger holds his readers in high regard – possibly a little too highly. When Eilenberger writes about the friendship between Wittgenstein and philosopher Bertrand Russell, it would be interesting to learn more about the ideas of Russell. But if you want to know more about Russell’s work – or the works of Kant or Husserl, who influenced these philosophers, for that matter – you will have to look them up yourself. When Eilenberger comments on a rather obscure philosophical point: ‘a child could have understood it,’ I wonder if I should perhaps ask a child to explain it to me, for Eilenberger doesn’t. Another thing he doesn’t explain thoroughly is what the parallels and contrasts are between the theories of these philosophers. There are clearly common themes in their philosophy, but it is up to the reader to discern these themes and to understand how the philosophers’ ideas complement and contradict each other. This can give you the feeling that you are reading four intertwined biographies, rather than one story as a whole.

In Time of the Magicians, Eilenberger manages to explain some very complicated philosophical ideas in an almost-comprehensible manner – not a small feat considering the complexity of the philosophical theories he writes about. Nevertheless, if you are looking for a light read, or a primer in philosophy, this might not be the book for you. If you wish to know more about the ideas of these four philosophers, however, already have some background knowledge in philosophy, and plenty of time to read the book slowly and carefully, one page at a time, you may find Time of the Magicians an interesting read.

Available at your local book store or online, starting from €17,89. A Dutch translation is also available: Tijdperk van de Tovenaars, starting from €34,99.