In recent years, there has been an increasing number of exonerations in the United States (USA). It is puzzling that, despite intense interrogations and the supposed high-level technological equipment in existence, thousands of false convictions are still made. Why does this keep happening?

In recent years, there has been an increasing number of exonerations in the United States (USA). It is puzzling that, despite intense interrogations and the supposed high-level technological equipment in existence, thousands of false convictions are still made. Why does this keep happening?

Image by Rogier Alleblas

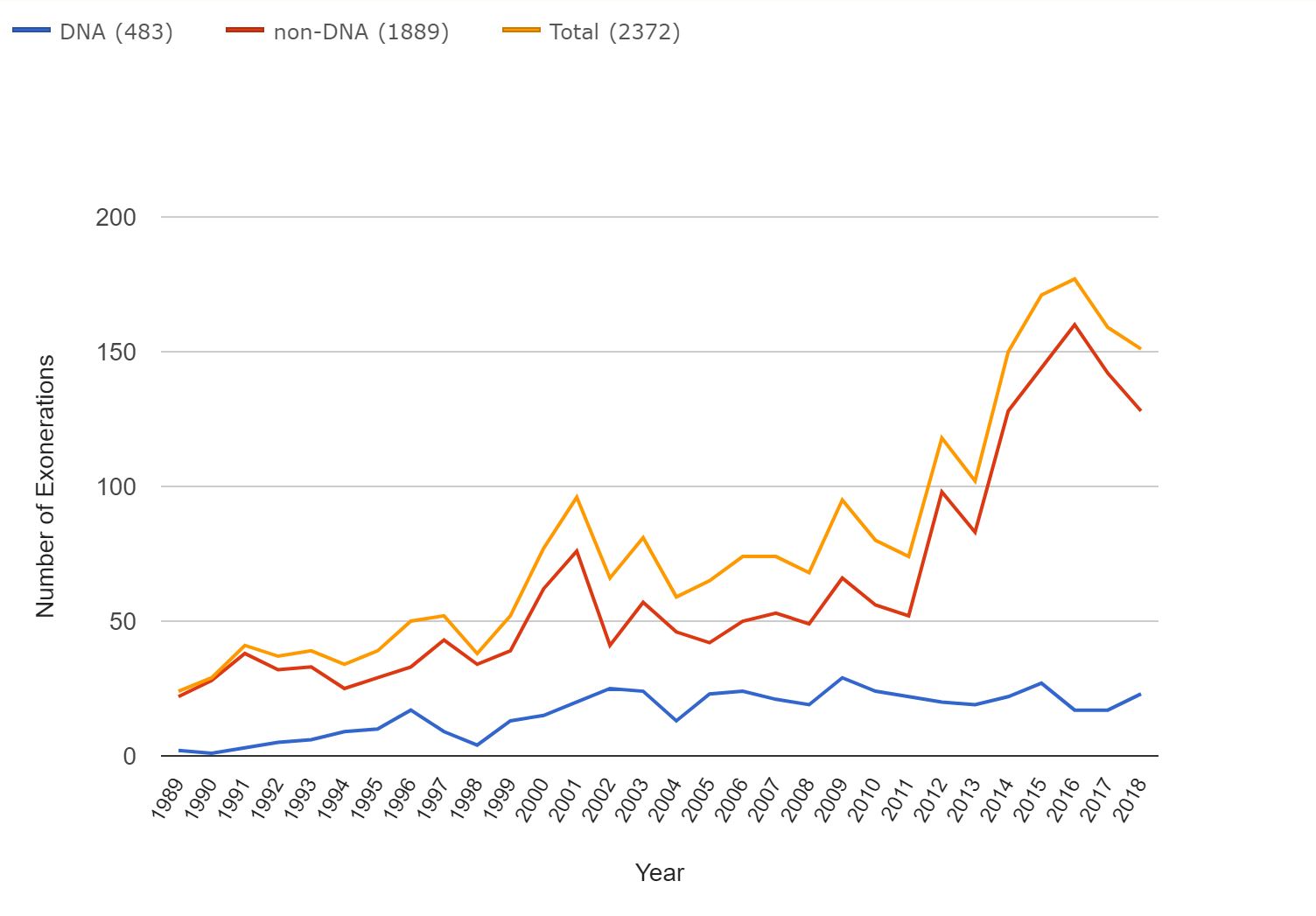

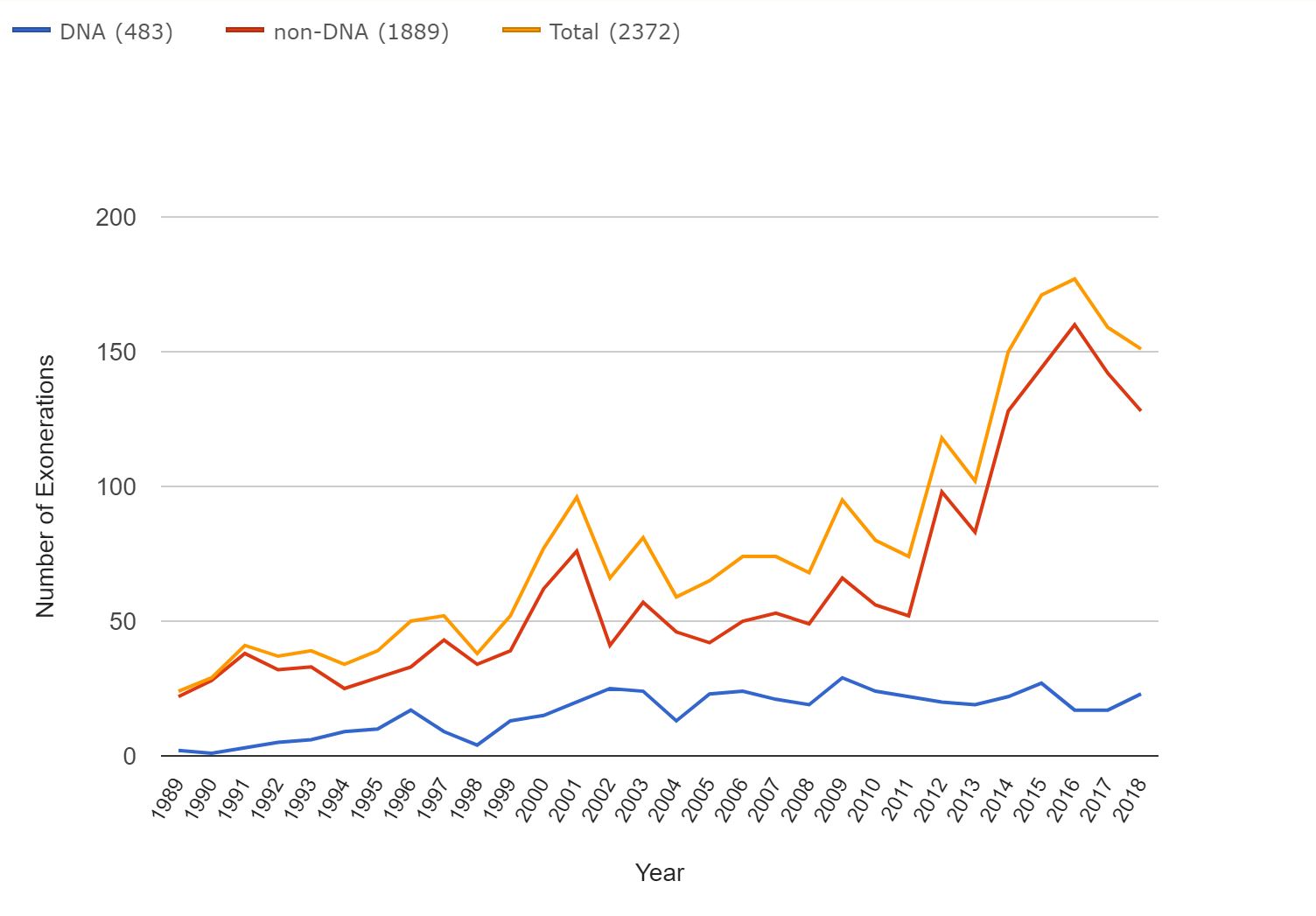

According to the Oxford dictionary, justice is the quality of being fair and reasonable (“Justice”, n.d.). The justice system, based on the law governing the country, can only carry out its function well when every part – from the police department to the court proceedings – is objective and transparent for all to see (“What is justice?”, n.d.). However, there are instances when one or more parts of the system fails, which then results in falsely convicted cases. The reason for the recent increase in exonerations (see Figure 1) is mostly due to the rise in ‘professional exonerators’.

Image retrieved from umich.edu.

As psychologists, the question we turn to is what the social biases and influences are that result in a false conviction? In the USA, racial prejudice contributes to a large number of false convictions – 63% of the people exonerated by DNA evidence are African-Americans (Grimsley, 2012). There is an obvious racial bias in the US justice system which can be seen by the fact that more African-American men are framed for crimes, wrongly identified by eyewitnesses, and given harsher convictions compared to their white counterparts – such as having a longer sentence by five to ten percent (Barone, 2017). Usually, this racial prejudice comes in the form of an implicit bias which is a bias that one may have without conscious awareness (Richardson, 2012). In addition, confirmation bias causes people to seek information that confirms their suspicions or previously registered information. Thus, if people are implicitly biased against a certain racial group, they will look for information that supports their bias. The information found influences the interpretations of subsequent information (Nakhaeizadeh, 2015). A more severe psychological phenomenon that branches off from confirmation bias is tunnel vision – when other information is rejected if it contradicts the seemingly ‘relevant’ information at hand.

The case of Robert Lee Stinson, in which the evidence of bite marks was brought forwards, illustrates the idea of confirmation bias. The forensic experts, knowing the trial information, declared the bite marks of the rape-murder victim as matching the bite marks of Stinson. Based on the facts that Stinson is African-American, was near the crime scene, had a missing tooth (which looked like it matched the bite mark), and was inconsistent about his whereabouts, the experts were probably mainly looking for evidence to incriminate Stinson. It was only 23 years later that Stinson was exonerated when it was found that the bite marks did not match (“Robert Lee Stinson”, n.d.)

“63% of the people exonerated by DNA evidence are African-Americans”

While biases can influence our thoughts, a more insidious mechanism that can obscure justice is the way memory is manipulated through methods such as leading questions or coercion. A common example is the study of a car accident where participants were asked to estimate the speed at which two cars collided, and either ‘smash’ or ‘hit’ was used to describe the impact. Those who heard ‘smash’ tended to estimate a higher speed and reported broken glass when there was none (Loftus, 1975). This research shows how leading questions can distort a person’s recollection of an event. Another error that commonly occurs is the wrong identification of a perpetrator. According to Smalarz and Wells (2015), this is due to the eyewitness self-reports being contaminated by other factors such as the reward of being a ‘good’ witness, which is when the idea of identifying someone as the perpetrator and ‘being an upstanding citizen’ becomes synonymous. Furthermore, witnesses may believe or be led to believe that at least one person in the line-up is the perpetrator when it could be that none of them are related to the crime. With this expectation, witnesses may feel pressured and be more likely to identify ‘the perpetrator’ in a line-up.

On the side of the accused, people can be coerced into falsely confessing to a crime they did not commit when put under pressure and given false information, for example that evidence against them has been found. The pressure and set up of the interrogation can make the accused vulnerable to suggestions by the interrogator, and thus causing the false evidence to result in a distortion of the memory of the accused. This can lead to a very believable false confession which, even when revealed as a coerced confession and removed from the database of evidence, can still influence jurors (Kassin, 1997). Furthermore, a study by Damme and Smets (2014) showed the ability of rich-false memories to be formed through the power of suggestion. It was found that participants were more open to believing false suggestions of information after frequent viewing of an event. In addition, strong emotions negatively affected memory for peripheral information, due to the narrowing of attention, which resulted in the participants being more susceptible to believing and reporting false information. Thus, if these tactics are used during the interrogation process (and they often are), the accused may form false memories of the event and confess to a crime they did not commit. Once they confess, this piece of information shapes the impression of the jurors irreversibly which can result in a false conviction.

“Witnesses may feel pressured and be more likely to identify ‘the perpetrator’ in a line-up.”

While there are false convictions, there are also people like those in the Innocent Project (a prominent American group aimed at upholding justice for those falsely convicted) who seek to restore justice. For those who have an interest in forensic psychology, this is a brief summary of how the meaning of justice can be preserved. To correct witness misidentification – one of the leading causes of false convictions – the instruction given is critical. The witness should note the possibility of the perpetrator not being in the line-up and to not take reference from the administrators. A blind set-up can also be arranged to prevent experimenter effects of the administrators (Norris, Bonventre, Redlich, Acker, & Lowe, 2017). False confessions in this case can be minimised by having a lawyer present. It seems that the accused feels less pressured by manipulative tactics – possibly due to the moral support from the lawyer – and may reduce the degree of coercive tactics used by the interrogator. In addition, the presence of a lawyer can prevent tunnel vision, as the lawyer may act as an opposing force to remind interrogators that the accused may not be guilty (Verhoeven, 2016).

While this article has explored the distortions of justice and how they have occurred, as well as measures to correct these distortions, an unanswered question remains: Does the meaning of justice still stand? Or is it lost? Will it continue to be stained by corrupt techniques and human biases despite efforts to correct these infractions? Unfortunately, I do not possess the answers to these questions. Personally, I would like to believe that there is meaning in justice, but I cannot ignore the tiny voice in the recesses of my mind that questions what the meaning of justice is. One meaningful quality of justice is its supposed fair and objective nature. Then again, is it not a subjective construct created by humans to provide some structure and order to the chaos we call life? Justice is built on laws but enacted by people, and people are but fickle beings. Even if the law is objective and unshakeable, the behaviours of people are influenced by many factors, as we learn in psychology. Therefore, in my opinion, while justice itself has meaning, it is distorted when in the hands of humans. <<

References

– [Image] Retrieved at April 3, 2019 from http://www.law.umich.edu/special/exoneration/Pages/Exoneration-by-Year.aspx/.

– Barone, E. (2017, February 17). The Wrongly Convicted. Retrieved on March 11, 2019 from: http://time.com/wrongly-convicted/

“Justice”. (n.d.). Retrieved from: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/justice/.

– Grimsley, E. (2012). What wrongful convictions teach us about racial inequality. Retrieved March 25, 2019 from: https://www.innocenceproject.org/what-wrongful-convictions-teach-us-about-racial-inequality/.

– Kassin, S. M., & Sukel, H. (1997). Coerced confessions and the jury: An experimental test of the “harmless error” rule. Law and Human Behavior, 21(1), 27-46.

– Loftus, E. F., & Zanni, G. (1975). Eyewitness testimony: The influence of the wording of a question. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 5(1), 86-88.

– Nakhaeizadeh, S., Dror, I. E., & Morgan, R. M. (2015). The Emergence of Cognitive Bias in Forensic Science and Criminal Investigations. British Journal of American Legal Studies, 4, 527.

– Norris, R. J., Bonventre, C. L., Redlich, A. D., Acker, J. R., & Lowe, C. (2017). Preventing wrongful convictions: An analysis of state investigation reforms. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 1-30.

– Richardson, L. S., & Goff, P. A. (2012). Implicit racial bias in public defender triage. The Yale Law Journal, 122, 2626.

– Robert Lee Stinson. (n.d.). Retrieved from: https://www.innocenceproject.org/cases/robert-lee-stinson/.

– Smalarz, L., & Wells, G. L. (2015). Contamination of eyewitness self-reports and the mistaken-identification problem. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(2), 120-124.

– Van Damme, I., & Smets, K. (2014). The power of emotion versus the power of suggestion: Memory for emotional events in the misinformation paradigm. Emotion, 14(2), 310.

– Verhoeven, W. J. (2018). The complex relationship between interrogation techniques, suspects changing their statement and legal assistance. Evidence from a Dutch sample of police interviews. Policing and Society, 28(3), 308-327.

– “What is justice?”. (n.d.). Retrieved from: http://www.civicsacademy.co.za/video/justice/.

According to the Oxford dictionary, justice is the quality of being fair and reasonable (“Justice”, n.d.). The justice system, based on the law governing the country, can only carry out its function well when every part – from the police department to the court proceedings – is objective and transparent for all to see (“What is justice?”, n.d.). However, there are instances when one or more parts of the system fails, which then results in falsely convicted cases. The reason for the recent increase in exonerations (see Figure 1) is mostly due to the rise in ‘professional exonerators’.

Image retrieved from umich.edu.

As psychologists, the question we turn to is what the social biases and influences are that result in a false conviction? In the USA, racial prejudice contributes to a large number of false convictions – 63% of the people exonerated by DNA evidence are African-Americans (Grimsley, 2012). There is an obvious racial bias in the US justice system which can be seen by the fact that more African-American men are framed for crimes, wrongly identified by eyewitnesses, and given harsher convictions compared to their white counterparts – such as having a longer sentence by five to ten percent (Barone, 2017). Usually, this racial pre-

judice comes in the form of an implicit bias which is a bias that one may have

without conscious awareness (Richardson, 2012). In addition, confirmation bias causes people to seek information that confirms their suspicions or previously registered information. Thus, if people are implicitly biased against a certain racial group, they will look for information that supports their bias. The information found influences the interpretations of subsequent information (Nakhaeizadeh, 2015). A more severe psychological phenomenon that branches off from confirmation bias is tunnel vision – when other information is rejected if it contradicts the seemingly ‘relevant’ information at hand.

The case of Robert Lee Stinson, in which the evidence of bite marks was brought forwards, illustrates the idea of confirmation bias. The forensic experts, knowing the trial information, declared the bite marks of the rape-murder victim as matching the bite marks of Stinson. Based on the facts that Stinson is African-American, was near the crime scene, had a missing tooth (which looked like it matched the bite mark), and was inconsistent about his whereabouts, the experts were probably mainly looking for evidence to incriminate Stinson. It was only 23 years later that Stinson was exonerated when it was found that the bite marks did not match (“Robert Lee Stinson”, n.d.)

“63% of the people exonerated by DNA evidence are African-Americans”

While biases can influence our thoughts, a more insidious mechanism that can obscure justice is the way memory is manipulated through methods such as leading questions or coercion. A common example is the study of a car accident where participants were asked to estimate the speed at which two cars collided, and either ‘smash’ or ‘hit’ was used to describe the impact. Those who heard ‘smash’ tended to estimate a higher speed and reported broken glass when there was none (Loftus, 1975). This research shows how leading questions can distort a person’s recollection of an event. Another error that commonly occurs is the wrong identification of a perpetrator. According to Smalarz and Wells (2015), this is due to the eyewitness self-reports being contaminated by other factors such as the reward of being a ‘good’ witness, which is when the idea of identifying someone as the perpetrator and ‘being an upstanding citizen’ becomes synonymous. Furthermore, witnesses may believe or be led to believe that at least one person in the line-up is the perpetrator when it could be that none of them are related to the crime. With this expectation, witnesses may feel pressured and be more likely to identify ‘the perpetrator’ in a line-up.

On the side of the accused, people can be coerced into falsely confessing to a crime they did not commit when put under pressure and given false information, for example that evidence against them has been found. The pressure and set up of the interrogation can make the accused vulnerable to suggestions by the interrogator, and thus causing the false evidence to result in a distortion of the memory of the accused. This can lead to a very believable false confession which, even when revealed as a coerced confession and removed from the database of evidence, can still influence jurors (Kassin, 1997). Furthermore, a study by Damme and Smets (2014) showed the ability of rich-false memories to be formed through the power of suggestion. It was found that participants were more open to believing false suggestions of information after frequent viewing of an event. In addition, strong emotions negatively affected memory for peripheral information, due to the narrowing of attention, which resulted in the participants being more susceptible to believing and reporting false information. Thus, if these tactics are used during the interrogation process (and they often are), the accused may form false memories of the event and confess to a crime they did not commit. Once they confess, this piece of information shapes the impression of the jurors irreversibly which can result in a false conviction.

“Witnesses may feel pressured and be more likely to identify ‘the perpetrator’ in a line-up.”

While there are false convictions, there are also people like those in the Innocent Project (a prominent American group aimed at upholding justice for those falsely convicted) who seek to restore justice. For those who have an interest in forensic psychology, this is a brief summary of how the meaning of justice can be preserved. To correct witness misidentification – one of the leading causes of false convictions – the instruction given is critical. The witness should note the possibility of the perpetrator not being in the line-up and to not take reference from the administrators. A blind set-up can also be arranged to prevent experimenter effects of the administrators (Norris, Bonventre, Redlich, Acker, & Lowe, 2017). False confessions in this case can be minimised by having a lawyer present. It seems that the accused feels less pressured by manipulative tactics – possibly due to the moral support from the lawyer – and may reduce the degree of coercive tactics used by the interrogator. In addition, the presence of a lawyer can prevent tunnel vision, as the lawyer may act as an opposing force to remind interrogators that the accused may not be guilty (Verhoeven, 2016).

While this article has explored the distortions of justice and how they have occurred, as well as measures to correct these distortions, an unanswered question remains: Does the meaning of justice still stand? Or is it lost? Will it continue to be stained by corrupt techniques and human biases despite efforts to correct these infractions? Unfortunately, I do not possess the answers to these questions. Personally, I would like to believe that there is meaning in justice, but I cannot ignore the tiny voice in the recesses of my mind that questions what the meaning of justice is. One meaningful quality of justice is its supposed fair and objective nature. Then again, is it not a subjective construct created by humans to provide some structure and order to the chaos we call life? Justice is built on laws but enacted by people, and people are but fickle beings. Even if the law is objective and unshakeable, the behaviours of people are influenced by many factors, as we learn in psychology. Therefore, in my opinion, while justice itself has meaning, it is distorted when in the hands of humans. <<