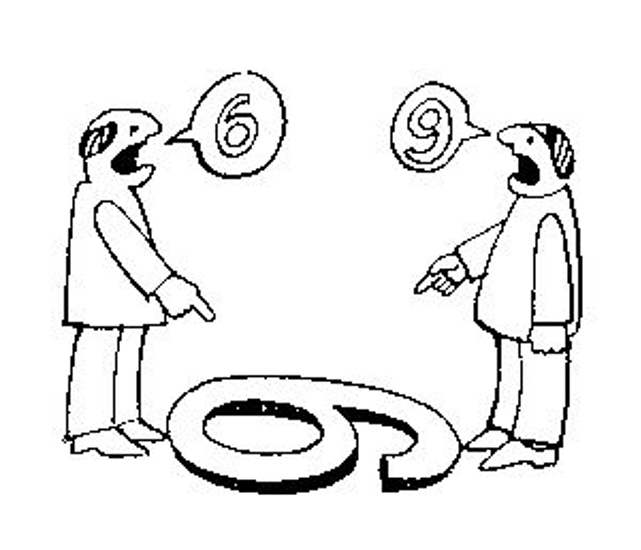

Growing up, the world may sometimes feel black and white: a right and wrong, a singular truth, a winner and a loser, with no space in between. This fixed thinking starts to waver when we are confronted with the more sophisticated dilemmas of life, be it through personal experience or theoretical situations; but it never truly leaves. It is hard to imagine that people can have fundamentally different inner workings and perceptions of situations, even though this is very much the case. What strikes one person as entirely irrational can be another person’s daily reality, and vice versa. One source of this phenomenon is cross-cultural differences, which people tend to overlook as a cause, or even a factor, in perception and understanding.

Growing up, the world may sometimes feel black and white: a right and wrong, a singular truth, a winner and a loser, with no space in between. This fixed thinking starts to waver when we are confronted with the more sophisticated dilemmas of life, be it through personal experience or theoretical situations; but it never truly leaves. It is hard to imagine that people can have fundamentally different inner workings and perceptions of situations, even though this is very much the case. What strikes one person as entirely irrational can be another person’s daily reality, and vice versa. One source of this phenomenon is cross-cultural differences, which people tend to overlook as a cause, or even a factor, in perception and understanding.

https://www.richardhughesjones.com/vuca/

https://www.richardhughesjones.com/vuca/

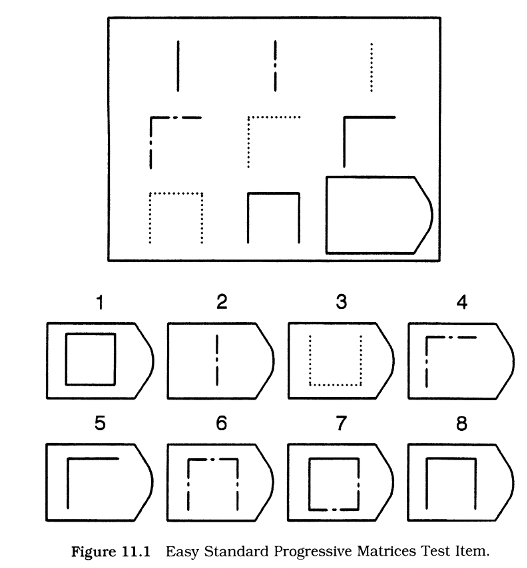

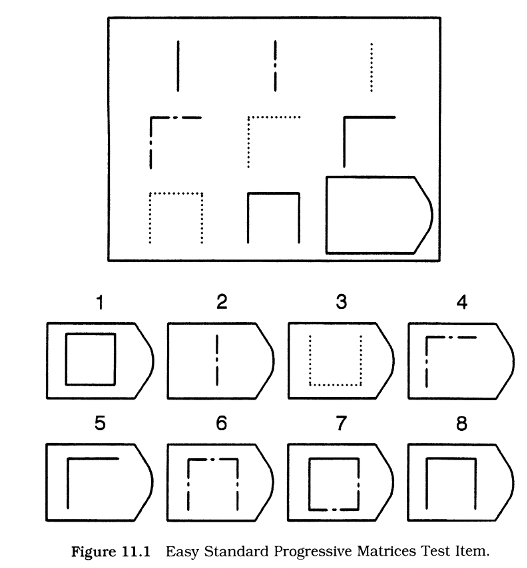

A significant illustration of this phenomenon lies in the use of Raven’s Progressive Matrices test as a measure of intelligence, where a person sees an incomplete pattern of drawings, and has to complete the progression based on what they think the pattern is. The test was created by John Raven as a possible assessment of people’s “eductive ability”, which generally refers to meaning-making (John & Raven, 2003). Because the test is non-verbal, it is assumed that it is less culturally bound, and therefore a valid measure of intelligence. However, Corentin Gonthier (2022), as well as many cross-cultural psychologists in the last 50 years, have argued that even the most rudimentary expectations about the conduction of any visuo-spatial task can be entirely unconsidered in another culture. He argues that aspects such as recognizing the drawings on paper as representations, or attention to the correct aspects of a paper medium are entirely overlooked when applying these tests in different cultures. For example, where one might expect to receive a Raven’s matrix and get on with solving it, another person might place emphasis on the negative space around the pattern or the quality of the paper, or entirely neglect that these drawings are representative of anything at all (Gonthier, 2022). What one human takes for granted, another may be completely unfamiliar with.

Raven, J., & Raven, J. (2003). Raven Progressive Matrices.

This is not to say that one mode of reasoning and perception is more ‘correct’ than another — it just points to irrationality being a subjective experience, with value being found in any one person’s approach, once elaborated upon. One line of research makes a distinction between analytic and holistic cognition (Varnum et al., 2010). Analytic cognition refers to a more narrow mode of thinking, where a person focuses more on a single dimension of what they perceive, as well as an attribution of intrinsic qualities as being the deciding factors in determining effects. For example, this would entail saying that the result of graduating university is due to the individual who graduated, without consideration for the professors, family, or other extrinsic factors. Holistic cognition can be seen as the opposite, where there is more emphasis on ‘the big picture’ and external factors as determinants for situations. For example, a study by Masuda and Nisbett (2001, as cited by Gray & Bjorklund, 2018) showed American and Japanese students a picture of an underwater fish scene, asking the students to later recall what they remember from the image. The American students placed a much larger emphasis on the biggest and most central aspects of the image, such as the big fish in the middle, while the Japanese students were better able to recall the entirety of what made up the image, with more attention to small details. However, when studied in children up to 6 years old, both American and Japanese children had a more holistic recollection of the image (Gray & Bjorklund, 2018). This is but one way in which we can see that your perceptions can be guided by your social context and the things you are taught to direct your attention to — what you actively attend to becomes your reality, but that reality is not the singular, ‘true’ one.

This may paint a rather bleak picture for the cultural sensitivity of perception and reasoning tests used in psychology, but the awareness of these discrepancies is already a step in the right direction. Perhaps this is a wake-up call that intelligence in itself, through its direct link to perception and reasoning methods, is relative in its interpretation in different social contexts. Not only do these discrepancies occur from one culture to another, but also appear within cultures. For example, just like differences in analytic and holistic cognition were found between American and Japanese students, the same distinction was seen between people from different areas in Japan (Kitayama, Ishii, et al., 2006, cited in Varum et al., 2010) and Italy (Knight & Nisbett, 2007, cited in Varum et al., 2010). All this goes to show is that misinterpretations in reasoning are not a simple distinction between people in completely different cultures, but may happen on any level of cultural difference, even in the same country.

“Perhaps this is a wake-up call that intelligence in itself, through its direct link to perception and reasoning methods, is relative in its interpretation in different social contexts.”

The big takeaway for any reader should be as follows: Do not be so quick to judge. A deeper understanding of an individual’s motives, lifestyle or priorities can shed valuable light on how they think, allowing for a creation of common ground in a place where only differences could be initially seen. It is not so much what you reason and perceive that is of primary importance, but rather how you do it, creating space for conversation and learning in any disagreement and misunderstanding.<<

References

– Gonthier, C. (2022). Cross-cultural differences in visuo-spatial processing and the culture-fairness of visuo-spatial intelligence tests: an integrative review and a model for matrices tasks. Cognitive Research: Principles and Implications, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41235-021-00350-w

– Gray, P. O., & Bjorklund, D. (2018). Psychology: 8th Edition. Macmillan Publishers.

- John, & Raven, J. (2003). Raven Progressive Matrices. Handbook of Nonverbal Assessment, 223–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-0153-4_11

– Raven, J., & Raven, J. (2003). Raven Progressive Matrices. In R. S. McCallum (Ed.), Handbook of nonverbal assessment (pp. 223–237). Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-0153-4_11

– Varnum, M. E. W., Grossmann, I., Kitayama, S., & Nisbett, R. E. (2010). The Origin of Cultural Differences in Cognition. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(1), 9–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721409359301

A significant illustration of this phenomenon lies in the use of Raven’s Progressive Matrices test as a measure of intelligence, where a person sees an incomplete pattern of drawings, and has to complete the progression based on what they think the pattern is. The test was created by John Raven as a possible assessment of people’s “eductive ability”, which generally refers to meaning-making (John & Raven, 2003). Because the test is non-verbal, it is assumed that it is less culturally bound, and therefore a valid measure of intelligence. However, Corentin Gonthier (2022), as well as many cross-cultural psychologists in the last 50 years, have argued that even the most rudimentary expectations about the conduction of any visuo-spatial task can be entirely unconsidered in another culture. He argues that aspects such as recognizing the drawings on paper as representations, or attention to the correct aspects of a paper medium are entirely overlooked when applying these tests in different cultures. For example, where one might expect to receive a Raven’s matrix and get on with solving it, another person might place emphasis on the negative space around the pattern or the quality of the paper, or entirely neglect that these drawings are representative of anything at all (Gonthier, 2022). What one human takes for granted, another may be completely unfamiliar with.

Raven, J., & Raven, J. (2003). Raven Progressive Matrices.

This is not to say that one mode of reasoning and perception is more ‘correct’ than another — it just points to irrationality being a subjective experience, with value being found in any one person’s approach, once elaborated upon. One line of research makes a distinction between analytic and holistic cognition (Varnum et al., 2010). Analytic cognition refers to a more narrow mode of thinking, where a person focuses more on a single dimension of what they perceive, as well as an attribution of intrinsic qualities as being the deciding factors in determining effects. For example, this would entail saying that the result of graduating university is due to the individual who graduated, without consideration for the professors, family, or other extrinsic factors. Holistic cognition can be seen as the opposite, where there is more emphasis on ‘the big picture’ and external factors as determinants for situations. For example, a study by Masuda and Nisbett (2001, as cited by Gray & Bjorklund, 2018) showed American and Japanese students a picture of an underwater fish scene, asking the students to later recall what they remember from the image. The American students placed a much larger emphasis on the biggest and most central aspects of the image, such as the big fish in the middle, while the Japanese students were better able to recall the entirety of what made up the image, with more attention to small details. However, when studied in children up to 6 years old, both American and Japanese children had a more holistic recollection of the image (Gray & Bjorklund, 2018). This is but one way in which we can see that your perceptions can be guided by your social context and the things you are taught to direct your attention to — what you actively attend to becomes your reality, but that reality is not the singular, ‘true’ one.

This may paint a rather bleak picture for the cultural sensitivity of perception and reasoning tests used in psychology, but the awareness of these discrepancies is already a step in the right direction. Perhaps this is a wake-up call that intelligence in itself, through its direct link to perception and reasoning methods, is relative in its interpretation in different social contexts. Not only do these discrepancies occur from one culture to another, but also appear within cultures. For example, just like differences in analytic and holistic cognition were found between American and Japanese students, the same distinction was seen between people from different areas in Japan (Kitayama, Ishii, et al., 2006, cited in Varum et al., 2010) and Italy (Knight & Nisbett, 2007, cited in Varum et al., 2010). All this goes to show is that misinterpretations in reasoning are not a simple distinction between people in completely different cultures, but may happen on any level of cultural difference, even in the same country.

“Perhaps this is a wake-up call that intelligence in itself, through its direct link to perception and reasoning methods, is relative in its interpretation in different social contexts.”

The big takeaway for any reader should be as follows: Do not be so quick to judge. A deeper understanding of an individual’s motives, lifestyle or priorities can shed valuable light on how they think, allowing for a creation of common ground in a place where only differences could be initially seen. It is not so much what you reason and perceive that is of primary importance, but rather how you do it, creating space for conversation and learning in any disagreement and misunderstanding.<<