Most of us have never and will never get anywhere near to experiencing what daily life is like for those behind bars. While hopefully, most prisoners are worthy of their sentences, the question that remains is – are prisons effective? Are they moral? Is there a better way to treat criminals?

These questions might sound ludicrous – after all, those that serve a prison sentence should be deserving of it. The longer the sentence, the more horrible the crime behind it. So why should we be concerned with prisoners’ general well-being while behind bars? We argue that a convicted felon or not, basic human rights should be defended for every human being. And many prisons are more than likely to violate quite a few of these rights.

Most of us have never and will never get anywhere near to experiencing what daily life is like for those behind bars. While hopefully, most prisoners are worthy of their sentences, the question that remains is – are prisons effective? Are they moral? Is there a better way to treat criminals?

These questions might sound ludicrous – after all, those that serve a prison sentence should be deserving of it. The longer the sentence, the more horrible the crime behind it. So why should we be concerned with prisoners’ general well-being while behind bars? We argue that a convicted felon or not, basic human rights should be defended for every human being. And many prisons are more than likely to violate quite a few of these rights.

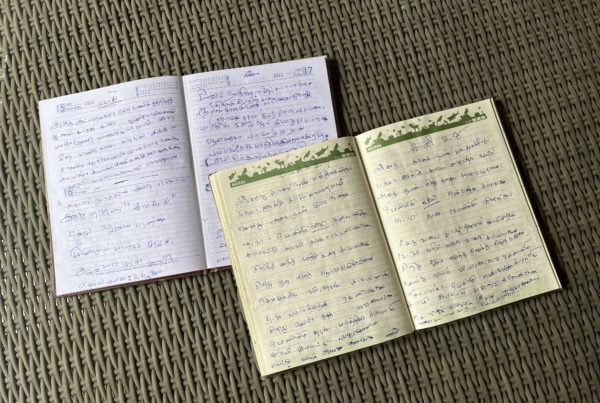

Photo by Hasan Almasi on Unsplash

Photo by Hasan Almasi on Unsplash

If you are not up to date with your serial killer knowledge, let us catch up on who Jeffrey Dahmer is and the horrible acts he carried out in his lifetime. Throughout the late 70s and early 90s in America, Dahmer committed 17 gruesome murders, was a sex offender, and even had cannibalistic tendencies. All of this should be enough to already spark some disgust and hatred towards Dahmer in any reader. In 1992, Dahmer was announced legally sane and found guilty of 15 of the murders, thus, sentenced to 15 terms of life imprisonment. His story ends shortly after being imprisoned, where Dahmer was beaten to death in 1994 at the hand of a fellow inmate, who despised his history of murder and assault (Biography, n.d.).

“What happens in prison, stays in prison.”

We remember when we first got acquainted with Dahmer’s story and its ending. Despite knowing in detail what kind of horrendous acts he committed, we didn’t celebrate his death. We felt puzzled. He had already received a harsh sentence of spending the rest of his life in prison. We learned that he had started getting involved with religion, he had even asked for baptism. We thought about what kind of path his life could have taken, had he not been killed. Did he deserve to die in such a way, despite his history of violence and murder? For that matter, what about the countless others imprisoned who are beaten daily, sexually assaulted, tormented, and even killed while behind bars? Reports show death by homicide in prisons increased by 267% between 2001 and 2019, and that 2.2% of deaths in state prisons are homicides (Carson & Cowhig, 2020) Even if this number may appear small, in a highly-controlled setting, such as a prison, it should be much closer to zero. Moreover, papers show many present instances of ill-treatment, sexual violence, and use of physical force, inflicted by both inmates and staff on those imprisoned (Krieger, 2019). So who cares for those behind bars and considers what their lives could have been like, had they managed to serve their sentences, be released, and start anew? It appears to be what happens in prisons, stays in prisons.

In a United States study, it was found that 48% of the examined inmates (a total of 8574) were diagnosed, according to the DSM-IV, with some form of mental illness, with 29% of those diagnosed with a serious mental disorder, and many of whom had more than one disorder (Al-Rousan et al., 2017). The most prevalent disorders were depression, anxiety, personality disorders, psychotic disorders, developmental disabilities, and post-traumatic stress disorder. These alarmingly high prevalence rates of mental illnesses raise the questions – how do prisoners receive help with their mental disorders, and how do the high rates of maltreatment and violence in prisons affect them further? Some prior papers also ask mental health professionals to take special care of those mentally ill in prisons (Yi et al., 2016). Despite their criminal pasts, those imprisoned are still people deserving of good physical and mental health treatment.

One particularly troubling aspect of prisons is solitary confinement. Research has already uncovered that social and physical pain share common physiological mechanisms (MacDonald & Leary, 2005). Social pain, in the form of social exclusion and feelings of loneliness, can be much more hurtful than one would anticipate and has often been described using words of physical pain, such as ‘broken heart’. This hints at how social pain is experienced almost in the same way as physical pain (Eisenberger & Lieberman, 2004). In our daily life, it often happens that we end up alone for a bit – be it if we live alone, prefer to study alone at home, or have a job that involves less contact with others. However, in prisons, solitary confinement occurs to much higher extremes than it does in traditional, daily life. Prisoners are forced to remain in windowless cells with no external stimulation, little or dim lighting, and no social communication (Smith, 2018). Thus, the effects of this confinement are much more pronounced (Haney, 2021).

Many prisoners under solitary confinement have reported a wide array of symptoms, such as heart palpitations, trembling, and even fainting. The psychological effects of social isolation included stress, intrusive thoughts, over-sensitivity to stimuli, unprovoked anger, and difficulties with attention and memory. Many prisoners engaged in self-harm and suffered headaches while socially isolated. One of the behavioural consequences of having to endure such confinement is the adaptation to being alone – which includes social withdrawal and the inability to form meaningful connections with others. These consequences are harmful and long-lasting, further leading to hallucinations, great fatigue, a feeling of ‘going mad’ (Haney, 2021), and many physical issues, such as neck and back pain, from the lack of exercise (Wikipedia, n.d.). Lastly, neuroscientists have stated that the lack of windows and good lighting may cause severe, irreversible brain damage, resulting from higher cortisol levels and blood pressure, and inflammation (Smith, 2018).

“Life inside the prison should be kept as similar to the outside world as possible.”

Given that prison comes with these conditions, we wonder whether it is a humane system. After all, prisoners are still humans. According to Coyle (2003), a prison system is humane if it contains these four elements: preservation of human dignity, respect for individuality, support for family life and promotion of personal responsibility and development. However, these conditions are not always met. Take for instance the element of human dignity. Prisoners should be able to clean themselves in private, without having their nakedness exposed to others. Yet, prisoners often have to shower simultaneously in a shared space. Not only does this strip them of their privacy, but it also puts them at risk for sexual harassment. Furthermore, prisoners’ individuality is respected by treating prisoners with empathy. For instance, prison staff would be empathic by informing a prisoner of negative news (e.g. death of a family member) in a compassionate and kind way, rather than in a rude or condescending manner. Yet, prisoners are often ridiculed or even abused by guards. For instance, prison guards are often able to physically abuse inmates through beatings (FogelLaw, n.d.). These beatings might go so far as to cause serious injuries, such as broken bones or internal bleeding (FogelLaw, n.d.). In addition, 4.4% of prisoners in the USA report experiencing sexual assault perpetrated by a guard (FogelLaw, n.d.). These are things we do not tolerate within everyday society. We would all be appalled if we heard of someone who was unable to shower in private or if someone were ridiculed for a family member’s death. And yet, we allow this to happen behind closed doors.

One prison system that is considered more ethical, is the one in Norway. A crucial aspect of this system is the fact that life inside the prison should be kept as similar to the outside world as possible (Denny, 2016). You might wonder whether this is sufficient punishment for the crime(s) that the prisoners have committed. As the Directorate of Norwegian Correctional Service states, the punishment for prisoners is simply meant to be the restriction of their freedom. As for the staff working in the prison, it is not their task to revoke even more of the prisoners’ freedom. Rather, the staff is meant to support the prisoners in rehabilitation. This supports the prisoners in preparing them for reintegration into society, which is the ultimate goal of a prison sentence. This contrasts with other prisons since those might be based solely on punishment (as opposed to rehabilitation) (Dahl & Mogstad, 2020). The benefits of the Norwegian prison system might be reflected in the rates of recidivism compared to other countries. For instance, rates of recidivism two years after release from prison are 20% in Norway, while 36% of American prisoners reoffend within two years of their release (Fazel & Wolf, 2015).

In contrast to American prison guards, Norwegian prison guards also act as social workers for the prisoners they are assigned to. Specifically, every guard is assigned two or three prisoners for whom they serve as the “contact officer” (Berlioz, 2019). The contact officer might assist the prisoner in determining their goals for the future, as well as what they might work towards while they are spending time in prison (Berlioz, 2019). As for stress, prisoners are also able to discuss this with their contact officer. Finally, the guards are expected to socialize with the prisoners, to diffuse the power imbalance between them. For instance, guards eat meals together with the prisoners (Berlioz, 2019). When considering all these responsibilities of the Norwegian prison guards, it becomes clear that they are meant to be allies for the prisoners, rather than people who serve out punishments. This acknowledges the humanity of the prisoners, which is something they still have a right to.

In this article, we argued that the current prison system is far from effective, and we explored how it violates basic human rights. We believe that a convicted criminal should serve their sentence and not end up killed and forgotten in prison, driven mad by isolation, tormented by staff and inmates, and should be able to receive proper mental health care. We recognize that prisons are meant to punish, but they should not go as far as greatly disturbing a human beyond the point of them being able to function in society upon their release. The prison system should be improved to aid the reintegration of those who served their sentence and better society and humanize life behind bars. <<

References

– Al-Rousan, T., Rubenstein, L., Sieleni, B., Deol, H., & Wallace, R. B. (2017). Inside the nation’s largest mental health institution: A prevalence study in a state prison system. BMC public health, 17(1), 1-9.

– Berlioz, D. (2019). “We are more like social workers than guards”. The European Trade Union Institute’s health and safety at work magazine, 19.

– Carson, E. A., & Cowhig, M. P. (2020). Mortality in state and federal prisons, 2001–2016 statistical tables. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics.

– Coyle, A. (2003). Humanity in Prison: questions of definition and audit. International Centre for Prison Studies.

– Dahl, G. B., & Mogstad, M. (2020). The benefits of rehabilitative incarceration. NBER Reporter, (1), 18-21.

– Denny, M. (2016). Norway’s prison system: Investigating recidivism and reintegration. Bridges: A Journal of Student Research, 10, 22-37. https://digitalcommons.coastal.edu/bridges/vol10/iss10/2

– Eisenberger, N. I., & Lieberman, M. D. (2004). Why rejection hurts: a common neural alarm system for physical and social pain. Trends in cognitive sciences, 8(7), 294-300.

– Fazel, S. & Wolf, A. (2015). A systematic review of criminal recidivism rates worldwide: Current difficulties and recommendations for best practice. PLoS ONE, 10, e0130390. 10.1371/journal.pone.0130390

– FogelLaw. (n.d.) Inmate abuse by corrections officer and the legal recourse available. Retrieved June 14, 2022 from https://www.nsfogel.com/articles/inmate-abuse-by-corrections-officers-and-the-legal-recourse-available/

– Haney, C. (2021). Solitary Confinement Is Not “Solitude” The Worst Case Scenario of Being “Alone” in Prison. The Handbook of Solitude: Psychological Perspectives on Social Isolation, Social Withdrawal, and Being Alone, 390-403.

– Jeffrey Dahmer. (2021, August 13). Biography. Retrieved June 10, 2022, from https://www.biography.com/crime-figure/jeffrey-dahmer

– Krieger, A. (2019, November 22). UN reports mortality rates for people in prison as much as 50 percent higher than wider community. Penal Reform International. Retrieved June 10, 2022, from https://www.penalreform.org/blog/un-reports-mortality-rates-for-people-in-prison/

– MacDonald, G., & Leary, M. R. (2005). Why does social exclusion hurt? The relationship between social and physical pain. Psychological bulletin, 131(2), 202.

– Smith, D. G. (2018, November 9). Neuroscientists Make a Case against Solitary Confinement. Scientific American. Retrieved June 13, 2022, from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/neuroscientists-make-a-case-against-solitary-confinement/

– Solitary confinement. (2022, June 7). Wikipedia. Retrieved June 13, 2022, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solitary_confinement#Effects

– Yi, Y., Turney, K., & Wildeman, C. (2017). Mental health among jail and prison inmates. American Journal of Men’s Health, 11(4), 900-909.

If you are not up to date with your serial killer knowledge, let us catch up on who Jeffrey Dahmer is and the horrible acts he carried out in his lifetime. Throughout the late 70s and early 90s in America, Dahmer committed 17 gruesome murders, was a sex offender, and even had cannibalistic tendencies. All of this should be enough to already spark some disgust and hatred towards Dahmer in any reader. In 1992, Dahmer was announced legally sane and found guilty of 15 of the murders, thus, sentenced to 15 terms of life imprisonment. His story ends shortly after being imprisoned, where Dahmer was beaten to death in 1994 at the hand of a fellow inmate, who despised his history of murder and assault (Biography, n.d.).

“What happens in prison, stays in prison.”

We remember when we first got acquainted with Dahmer’s story and its ending. Despite knowing in detail what kind of horrendous acts he committed, we didn’t celebrate his death. We felt puzzled. He had already received a harsh sentence of spending the rest of his life in prison. We learned that he had started getting involved with religion, he had even asked for baptism. We thought about what kind of path his life could have taken, had he not been killed. Did he deserve to die in such a way, despite his history of violence and murder? For that matter, what about the countless others imprisoned who are beaten daily, sexually assaulted, tormented, and even killed while behind bars? Reports show death by homicide in prisons increased by 267% between 2001 and 2019, and that 2.2% of deaths in state prisons are homicides (Carson & Cowhig, 2020) Even if this number may appear small, in a highly-controlled setting, such as a prison, it should be much closer to zero. Moreover, papers show many present instances of ill-treatment, sexual violence, and use of physical force, inflicted by both inmates and staff on those imprisoned (Krieger, 2019). So who cares for those behind bars and considers what their lives could have been like, had they managed to serve their sentences, be released, and start anew? It appears to be what happens in prisons, stays in prisons.

In a United States study, it was found that 48% of the examined inmates (a total of 8574) were diagnosed, according to the DSM-IV, with some form of mental illness, with 29% of those diagnosed with a serious mental disorder, and many of whom had more than one disorder (Al-Rousan et al., 2017). The most prevalent disorders were depression, anxiety, personality disorders, psychotic disorders, developmental disabilities, and post-traumatic stress disorder. These alarmingly high prevalence rates of mental illnesses raise the questions – how do prisoners receive help with their mental disorders, and how do the high rates of maltreatment and violence in prisons affect them further? Some prior papers also ask mental health professionals to take special care of those mentally ill in prisons (Yi et al., 2016). Despite their criminal pasts, those imprisoned are still people deserving of good physical and mental health treatment.

One particularly troubling aspect of prisons is solitary confinement. Research has already uncovered that social and physical pain share common physiological mechanisms (MacDonald & Leary, 2005). Social pain, in the form of social exclusion and feelings of loneliness, can be much more hurtful than one would anticipate and has often been described using words of physical pain, such as ‘broken heart’. This hints at how social pain is experienced almost in the same way as physical pain (Eisenberger & Lieberman, 2004). In our daily life, it often happens that we end up alone for a bit – be it if we live alone, prefer to study alone at home, or have a job that involves less contact with others. However, in prisons, solitary confinement occurs to much higher extremes than it does in traditional, daily life. Prisoners are forced to remain in windowless cells with no external stimulation, little or dim lighting, and no social communication (Smith, 2018). Thus, the effects of this confinement are much more pronounced (Haney, 2021).

Many prisoners under solitary confinement have reported a wide array of symptoms, such as heart palpitations, trembling, and even fainting. The psychological effects of social isolation included stress, intrusive thoughts, over-sensitivity to stimuli, unprovoked anger, and difficulties with attention and memory. Many prisoners engaged in self-harm and suffered headaches while socially isolated. One of the behavioural consequences of having to endure such confinement is the adaptation to being alone – which includes social withdrawal and the inability to form meaningful connections with others. These consequences are harmful and long-lasting, further leading to hallucinations, great fatigue, a feeling of ‘going mad’ (Haney, 2021), and many physical issues, such as neck and back pain, from the lack of exercise (Wikipedia, n.d.). Lastly, neuroscientists have stated that the lack of windows and good lighting may cause severe, irreversible brain damage, resulting from higher cortisol levels and blood pressure, and inflammation (Smith, 2018).

“Life inside the prison should be kept as similar to the outside world as possible.”

Given that prison comes with these conditions, we wonder whether it is a humane system. After all, prisoners are still humans. According to Coyle (2003), a prison system is humane if it contains these four elements: preservation of human dignity, respect for individuality, support for family life and promotion of personal responsibility and development. However, these conditions are not always met. Take for instance the element of human dignity. Prisoners should be able to clean themselves in private, without having their nakedness exposed to others. Yet, prisoners often have to shower simultaneously in a shared space. Not only does this strip them of their privacy, but it also puts them at risk for sexual harassment. Furthermore, prisoners’ individuality is respected by treating prisoners with empathy. For instance, prison staff would be empathic by informing a prisoner of negative news (e.g. death of a family member) in a compassionate and kind way, rather than in a rude or condescending manner. Yet, prisoners are often ridiculed or even abused by guards. For instance, prison guards are often able to physically abuse inmates through beatings (FogelLaw, n.d.). These beatings might go so far as to cause serious injuries, such as broken bones or internal bleeding (FogelLaw, n.d.). In addition, 4.4% of prisoners in the USA report experiencing sexual assault perpetrated by a guard (FogelLaw, n.d.). These are things we do not tolerate within everyday society. We would all be appalled if we heard of someone who was unable to shower in private or if someone were ridiculed for a family member’s death. And yet, we allow this to happen behind closed doors.

One prison system that is considered more ethical, is the one in Norway. A crucial aspect of this system is the fact that life inside the prison should be kept as similar to the outside world as possible (Denny, 2016). You might wonder whether this is sufficient punishment for the crime(s) that the prisoners have committed. As the Directorate of Norwegian Correctional Service states, the punishment for prisoners is simply meant to be the restriction of their freedom. As for the staff working in the prison, it is not their task to revoke even more of the prisoners’ freedom. Rather, the staff is meant to support the prisoners in rehabilitation. This supports the prisoners in preparing them for reintegration into society, which is the ultimate goal of a prison sentence. This contrasts with other prisons since those might be based solely on punishment (as opposed to rehabilitation) (Dahl & Mogstad, 2020). The benefits of the Norwegian prison system might be reflected in the rates of recidivism compared to other countries. For instance, rates of recidivism two years after release from prison are 20% in Norway, while 36% of American prisoners reoffend within two years of their release (Fazel & Wolf, 2015).

In contrast to American prison guards, Norwegian prison guards also act as social workers for the prisoners they are assigned to. Specifically, every guard is assigned two or three prisoners for whom they serve as the “contact officer” (Berlioz, 2019). The contact officer might assist the prisoner in determining their goals for the future, as well as what they might work towards while they are spending time in prison (Berlioz, 2019). As for stress, prisoners are also able to discuss this with their contact officer. Finally, the guards are expected to socialize with the prisoners, to diffuse the power imbalance between them. For instance, guards eat meals together with the prisoners (Berlioz, 2019). When considering all these responsibilities of the Norwegian prison guards, it becomes clear that they are meant to be allies for the prisoners, rather than people who serve out punishments. This acknowledges the humanity of the prisoners, which is something they still have a right to.

In this article, we argued that the current prison system is far from effective, and we explored how it violates basic human rights. We believe that a convicted criminal should serve their sentence and not end up killed and forgotten in prison, driven mad by isolation, tormented by staff and inmates, and should be able to receive proper mental health care. We recognize that prisons are meant to punish, but they should not go as far as greatly disturbing a human beyond the point of them being able to function in society upon their release. The prison system should be improved to aid the reintegration of those who served their sentence and better society and humanize life behind bars.