At this moment, 7000 languages are spoken (Klappenabach, 2022). Although emotions are considered to be universal, they are also defined by the language we use. The way we express trivial things from shopping lists to ‘I love yous’, is dependent on our emotional connection to a language (Bakić & Škifić, 2017). As a Polish-English bilingual myself, the boundaries between what language I use when and with whom, aren’t always so clear.Often I find myself in situations where my friends make a remark or a joke in their native language mid-conversation. Yet, it takes a moment before they follow up with a translation upon the realisation that I didn’t actually understand them. Does this happen because their first language is the one in which they feel most comfortable expressing emotions, feel comfortable with me, or both?

At this moment, 7000 languages are spoken (Klappenabach, 2022). Although emotions are considered to be universal, they are also defined by the language we use. The way we express trivial things from shopping lists to ‘I love yous’, is dependent on our emotional connection to a language (Bakić & Škifić, 2017). As a Polish-English bilingual myself, the boundaries between what language I use when and with whom, aren’t always so clear.Often I find myself in situations where my friends make a remark or a joke in their native language mid-conversation. Yet, it takes a moment before they follow up with a translation upon the realisation that I didn’t actually understand them. Does this happen because their first language is the one in which they feel most comfortable expressing emotions, feel comfortable with me, or both?

Illustration by Anushka Sabhanam

Illustration by Anushka Sabhanam

Research by Benet-Martínez et al. (2002) points to bilingual people deciding upon a language in a given situation as being dependent on the construction of collective and individual identity through cultural frame shifting as well as differences in perception of oneself depending on language. For instance, if I just finished a phone call with my mother and then came across a Polish friend on my way to campus, I would be in a Polish cultural frame of mind. But later on in the day when I look at a drinks menu at a cafe and see a typical English brand of tea, I will switch to an English frame of mind as I am ´fluent´ in both cultures.

Do you ever find yourself repeating inside jokes with friends? The jokes – perhaps consciously or subconsciously – serve as a reminder of a bond shared with friends. These jokes define our comfort states within a group setting. Language as a tool for communication and a means of expressing comfort, is a part of social group identity via culture. Hall (1997) denotes culture as being composed of any unique qualities of a community’s lifestyle. In this sense, Hall outlines individuals sharing common expressions for speech and meaning as a culture. Similarly, other research has reflected that we use our first language to communicate intimacy and belonging (i.e saying ‘we do/eat this…’ even when talking on an individual level), while we designate the second language as a boundary to create a distanced attitude from a group (Pavlenko & Dewaele, 2004). Hence, language acts as a ‘filter’ between the culture we represent and another culture (Stroinska et al., 2003). Research by Stroinska et. al. (2003) makes an intriguing case of language being the only familiar and comforting factor for bonding with others, especially for individuals who choose to migrate abroad.

“Where a first language may lack an expression for a certain feeling, to a bilingual, a second language fills this gap.”

Although language may be presented simultaneously as a uniting and separating factor of collective identity, we might wonder if we modify, lose or attach ourselves to a completely new construct of our cultural identity when acquiring a second language (Stroinska et al., 2003). Learning another language involves learning a specific way certain thoughts and emotions are phrased in the target culture. For example, when I first moved to England I was surprised to find my old English lady neighbour greeting me with ´goodmorning, love´ or a peer saying ´thanks mate´. In Polish culture the words ´love´ and ´mate´ are quite strictly used within their definition by the dictionary. However, fast-forward a few months later, I understood that in English culture the words love and mate in daily conversation are no more than conversational accessories to show greeting and friendly acknowledgement. I now, after having lived in England for many years, find myself being the old English neighbour and confusing the cashier lady at Albert Hejin when she hears ´thanks love´ upon returning my change. This experience of a bicultural world involving language proficiency and partial belonging to two cultures is what defines bilingualism (Bakić & Škifić, 2017). Our personal differences in how we define identity, affect how we absorb cultural experiences and use them to understand the other culture on a group level (Benet-Martínez et al., 2002). We hence circle back and forth between cultural frames on the daily. However, it is important to note that this framing can vary depending on self-description and values we have towards family and friends which is influenced by what culture we feel a part of in the present moment (Verkuyten & Pouliasi, 2006).

A study by Verkuyten and Pouliasi (2006) manipulating the cultural frame shift across Dutch and Greek bilinguals, examined these respective factors by showcasing images and other symbols representative of that culture. Dutch individuals of Greek descent were primed to either the Dutch or Greek frame of mind. For self-description, subjects related most to words/phrases relevant to each culture’s stereotypes, and individuals’ attitudes reflected the collective attitude of the culture which they were primed with. Participants primed to the Dutch cultural frame univocally related the most to phrases in a questionnaire favouring individuality while participants primed to the Greek cultural frame showed the most relatability to ‘we’ statements. The same trend was observed when groups were asked to assess their familial and friendship values. Perhaps, people in Greece discuss their feelings with more ease in social interactions than in Dutch culture. Therefore, a culture’s relationship with allowing people to openly discuss their emotions may influence and limit what emotions are self-reported on an individual level. As a bilingual myself, I prefer to discuss feelings with close bicultural friends, preferably in English as I find greater comfort in the fact that talking about personal experiences is more common in British English culture than it is in Poland, where people’s attitudes are more reserved.

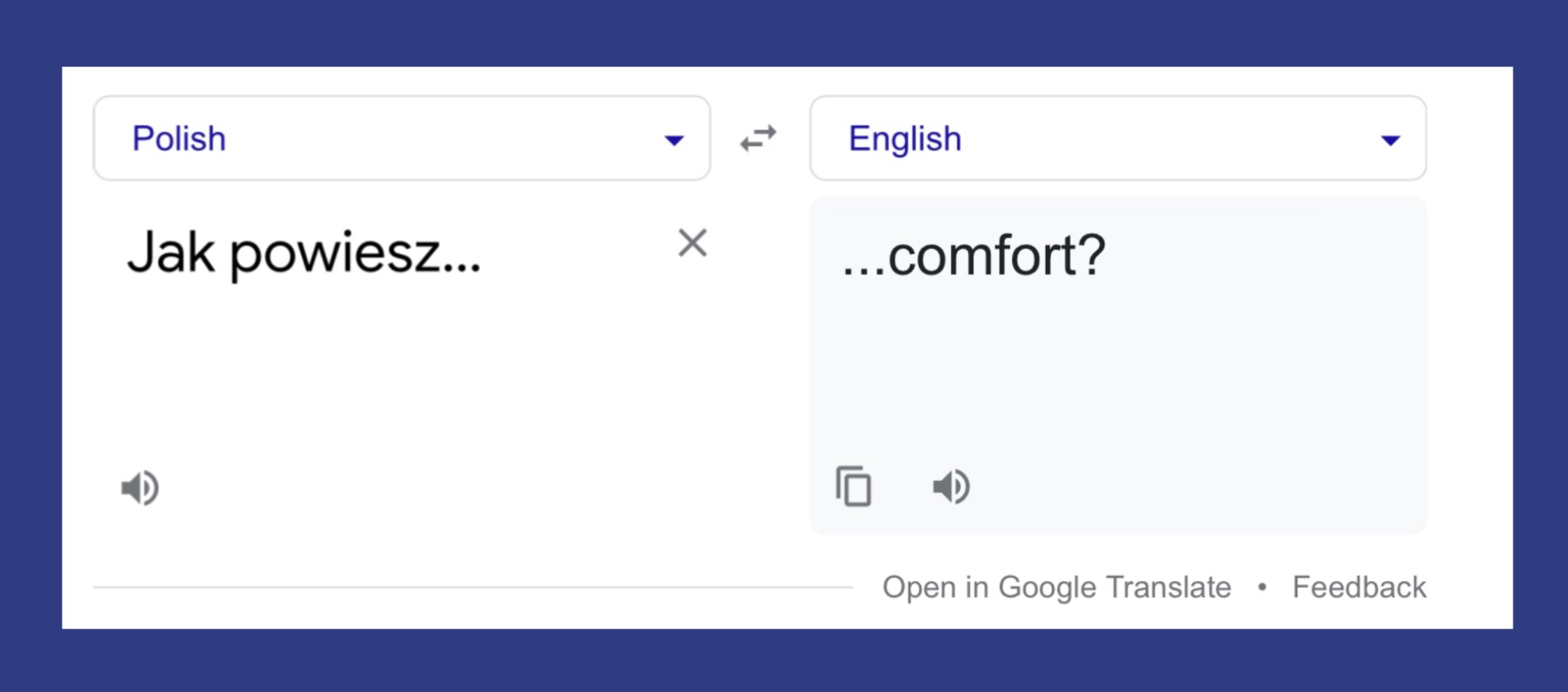

However, what defines one culture to an individual can be very different for another. The ways a person acquires understanding of the second culture is subjective. Do we find comfort in what we associate with a particular culture or do we find comfort in the way in which a certain language allows us to express ourselves? Whilst bicultural identity management (Verkuyten & Pouliasi, 2006) remains rather ambiguous in this regard, it’s important to consider how defining an emotion in one language may not be of equal personal value, when we translate the emotion to another language. Where a first language may lack an expression for a certain feeling, to a bilingual, a second language fills this gap.

“Perhaps, bilingualism is a language in itself and shouldn't be looked at as two separate emotional worlds but as a style of thought.”

Speaking a certain language not only emphasises a cultural association a bilingual may possess, but it may also evoke a different personality within them (Pavlenko & Dewaele, 2004). Bilinguals often alter their behaviour depending on what role they take on in a given setting and this is what Chen and Bond (2010) concluded in their study analysing perception in Hong Kong bilinguals. When at home speaking to family, the bilingual usually takes on the role of a family member and uses the first language more often, whereas when communicating with work colleagues, a different, more distanced role may be acquired by using their second language. The role a bilingual is currently in may influence their emotional reaction and hence the personality they display. In the same study, the bilinguals were asked to rate native Chinese and native English speakers across the Big Five personality factors. The bilingual observers reacted differently to the respective speakers; English speakers were perceived as more extraverted and open to experience, whereas Chinese native speakers were rated most often as agreeable and neurotic. In a second part of the same study, Cantonese speakers were viewed as humble and honest, whilst English speakers were reported as friendly and competent. Through this, it can be observed that bilinguals assign personality traits based on cultural identity and consequently may define their own personality through this lens.

At times, language can take on the form of a social safety belt in two contrasting ways. Pavlenko and Dewaele (2004) remarked that partners in bilingual couples use their first language when arguing, not only because it feels more comfortable in terms of ease and satisfaction, but also because the bilingual person’s partner doesn’t understand the language they speak. This allows the bilingual partner to express their anger without inflicting as much pain as would be experienced if a language understood by both parties was used. On the flip-side, for other bilinguals, the second language may be more preferred to express emotional relief (i.e anger) in conflict circumstances as using the second language doesn’t feel as impactful as the first due to the person’s own emotional attachment to the language itself. An individual’s connection to a second language depends on what circumstances they learned it in, as well as their age and personal stress when the language acquisition occurred (Bakić & Škifić, 2017). Whilst we may run to a certain language for comfort or to help us fit a certain social role, a second language also acts as an escape route for bilinguals during times of conflict.

As much as language can comfort us through the knowledge that we belong to a bigger group of people – whether that be a group of friends or a culture, language can hurt us too. Whether it be in allowing us to express anger more freely in a situation, or to appear assertive, knowing two languages works like wearing two pairs of shoes. Sometimes, one pair might be more comfortable or appropriate than the other. You change into slippers (first language) when you get home, but you would not wear them outside. Sometimes, the weather changes, and you might need to acquire a third pair. Perhaps, bilingualism is a language in itself and shouldn’t be looked at as two separate emotional worlds but as a style of thought. Your jokes, sayings or good morning phrases are where the true comfort and ease in language lies. <<

References

-

Bakić, A., & Škifić, S. (2017). The relationship between bilingualism and identity in expressing emotions and thoughts. Íkala, Revista De Lenguaje y Cultura, 22(2), 33–54. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.ikala.v22n01a03

-

Benet-Martínez, V., Leu, J., Lee, F., & Morris, M. W. (2002). Negotiating biculturalism: Cultural Frame Switching in Biculturals With Oppositional Versus Compatible Cultural Identities. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33(5), 492–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022102033005005

-

Chen, S. X., & Bond, M. H. (2010). Two languages, two personalities? examining language effects on the expression of personality in a bilingual context. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(11), 1514–1528. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167210385360

-

Hall, S. (1997). Cultural identity and diaspora. In K. Woodward (Ed.), Identity and difference (pp. 392–403).

-

Klappenabach, A. (2022, January 7). The 12 most spoken languages in the world. Retrieved November 1, 2022, from https://blog.busuu.com/most-spoken-languages-in-the-world/.

-

Pavlenko, A., & Dewaele, J.-M. (2004). Bilingualism & Emotions. Servicio de Publicacións da Universidade de Vigo.

-

Ringberg, T. V., Luna, D., Reihlen, M., & Peracchio, L. A. (2010). Bicultural-bilinguals: The Effect of Cultural Frame Switching on Translation Equivalence. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 10(1), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595809359585

-

Stroinska, M., & Cecchetto, V. (2003). The role of language in re-construction of identity in exile. In Exile, language and identity (pp. 95–105). essay, Peter Lang.

-

Verkuyten, M., & Pouliasi, K. (2006). Biculturalism and group identification: Cultural Frame Switching in Biculturals With Oppositional Versus Compatible Cultural Identities. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 37(3), 312–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022106286926

Research by Benet-Martínez et al. (2002) points to bilingual people deciding upon a language in a given situation as being dependent on the construction of collective and individual identity through cultural frame shifting as well as differences in perception of oneself depending on language. For instance, if I just finished a phone call with my mother and then came across a Polish friend on my way to campus, I would be in a Polish cultural frame of mind. But later on in the day when I look at a drinks menu at a cafe and see a typical English brand of tea, I will switch to an English frame of mind as I am ´fluent´ in both cultures.

Do you ever find yourself repeating inside jokes with friends? The jokes – perhaps consciously or subconsciously – serve as a reminder of a bond shared with friends. These jokes define our comfort states within a group setting. Language as a tool for communication and a means of expressing comfort, is a part of social group identity via culture. Hall (1997) denotes culture as being composed of any unique qualities of a community’s lifestyle. In this sense, Hall outlines individuals sharing common expressions for speech and meaning as a culture. Similarly, other research has reflected that we use our first language to communicate intimacy and belonging (i.e saying ‘we do/eat this…’ even when talking on an individual level), while we designate the second language as a boundary to create a distanced attitude from a group (Pavlenko & Dewaele, 2004). Hence, language acts as a ‘filter’ between the culture we represent and another culture (Stroinska et al., 2003). Research by Stroinska et. al. (2003) makes an intriguing case of language being the only familiar and comforting factor for bonding with others, especially for individuals who choose to migrate abroad.

“Where a first language may lack an expression for a certain feeling, to a bilingual, a second language fills this gap.”

Although language may be presented simultaneously as a uniting and separating factor of collective identity, we might wonder if we modify, lose or attach ourselves to a completely new construct of our cultural identity when acquiring a second language (Stroinska et al., 2003). Learning another language involves learning a specific way certain thoughts and emotions are phrased in the target culture. For example, when I first moved to England I was surprised to find my old English lady neighbour greeting me with ´goodmorning, love´ or a peer saying ´thanks mate´. In Polish culture the words ´love´ and ´mate´ are quite strictly used within their definition by the dictionary. However, fast-forward a few months later, I understood that in English culture the words love and mate in daily conversation are no more than conversational accessories to show greeting and friendly acknowledgement. I now, after having lived in England for many years, find myself being the old English neighbour and confusing the cashier lady at Albert Hejin when she hears ´thanks love´ upon returning my change. This experience of a bicultural world involving language proficiency and partial belonging to two cultures is what defines bilingualism (Bakić & Škifić, 2017). Our personal differences in how we define identity, affect how we absorb cultural experiences and use them to understand the other culture on a group level (Benet-Martínez et al., 2002). We hence circle back and forth between cultural frames on the daily. However, it is important to note that this framing can vary depending on self-description and values we have towards family and friends which is influenced by what culture we feel a part of in the present moment (Verkuyten & Pouliasi, 2006).

A study by Verkuyten and Pouliasi (2006) manipulating the cultural frame shift across Dutch and Greek bilinguals, examined these respective factors by showcasing images and other symbols representative of that culture. Dutch individuals of Greek descent were primed to either the Dutch or Greek frame of mind. For self-description, subjects related most to words/phrases relevant to each culture’s stereotypes, and individuals’ attitudes reflected the collective attitude of the culture which they were primed with. Participants primed to the Dutch cultural frame univocally related the most to phrases in a questionnaire favouring individuality while participants primed to the Greek cultural frame showed the most relatability to ‘we’ statements. The same trend was observed when groups were asked to assess their familial and friendship values. Perhaps, people in Greece discuss their feelings with more ease in social interactions than in Dutch culture. Therefore, a culture’s relationship with allowing people to openly discuss their emotions may influence and limit what emotions are self-reported on an individual level. As a bilingual myself, I prefer to discuss feelings with close bicultural friends, preferably in English as I find greater comfort in the fact that talking about personal experiences is more common in British English culture than it is in Poland, where people’s attitudes are more reserved.

However, what defines one culture to an individual can be very different for another. The ways a person acquires understanding of the second culture is subjective. Do we find comfort in what we associate with a particular culture or do we find comfort in the way in which a certain language allows us to express ourselves? Whilst bicultural identity management (Verkuyten & Pouliasi, 2006) remains rather ambiguous in this regard, it’s important to consider how defining an emotion in one language may not be of equal personal value, when we translate the emotion to another language. Where a first language may lack an expression for a certain feeling, to a bilingual, a second language fills this gap.

“Perhaps, bilingualism is a language in itself and shouldn't be looked at as two separate emotional worlds but as a style of thought.”

Speaking a certain language not only emphasises a cultural association a bilingual may possess, but it may also evoke a different personality within them (Pavlenko & Dewaele, 2004). Bilinguals often alter their behaviour depending on what role they take on in a given setting and this is what Chen and Bond (2010) concluded in their study analysing perception in Hong Kong bilinguals. When at home speaking to family, the bilingual usually takes on the role of a family member and uses the first language more often, whereas when communicating with work colleagues, a different, more distanced role may be acquired by using their second language. The role a bilingual is currently in may influence their emotional reaction and hence the personality they display. In the same study, the bilinguals were asked to rate native Chinese and native English speakers across the Big Five personality factors. The bilingual observers reacted differently to the respective speakers; English speakers were perceived as more extraverted and open to experience, whereas Chinese native speakers were rated most often as agreeable and neurotic. In a second part of the same study, Cantonese speakers were viewed as humble and honest, whilst English speakers were reported as friendly and competent. Through this, it can be observed that bilinguals assign personality traits based on cultural identity and consequently may define their own personality through this lens.

At times, language can take on the form of a social safety belt in two contrasting ways. Pavlenko and Dewaele (2004) remarked that partners in bilingual couples use their first language when arguing, not only because it feels more comfortable in terms of ease and satisfaction, but also because the bilingual person’s partner doesn’t understand the language they speak. This allows the bilingual partner to express their anger without inflicting as much pain as would be experienced if a language understood by both parties was used. On the flip-side, for other bilinguals, the second language may be more preferred to express emotional relief (i.e anger) in conflict circumstances as using the second language doesn’t feel as impactful as the first due to the person’s own emotional attachment to the language itself. An individual’s connection to a second language depends on what circumstances they learned it in, as well as their age and personal stress when the language acquisition occurred (Bakić & Škifić, 2017). Whilst we may run to a certain language for comfort or to help us fit a certain social role, a second language also acts as an escape route for bilinguals during times of conflict.

As much as language can comfort us through the knowledge that we belong to a bigger group of people – whether that be a group of friends or a culture, language can hurt us too. Whether it be in allowing us to express anger more freely in a situation, or to appear assertive, knowing two languages works like wearing two pairs of shoes. Sometimes, one pair might be more comfortable or appropriate than the other. You change into slippers (first language) when you get home, but you would not wear them outside. Sometimes, the weather changes, and you might need to acquire a third pair. Perhaps, bilingualism is a language in itself and shouldn’t be looked at as two separate emotional worlds but as a style of thought. Your jokes, sayings or good morning phrases are where the true comfort and ease in language lies. <<

References

-

Bakić, A., & Škifić, S. (2017). The relationship between bilingualism and identity in expressing emotions and thoughts. Íkala, Revista De Lenguaje y Cultura, 22(2), 33–54. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.ikala.v22n01a03

-

Benet-Martínez, V., Leu, J., Lee, F., & Morris, M. W. (2002). Negotiating biculturalism: Cultural Frame Switching in Biculturals With Oppositional Versus Compatible Cultural Identities. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33(5), 492–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022102033005005

-

Chen, S. X., & Bond, M. H. (2010). Two languages, two personalities? examining language effects on the expression of personality in a bilingual context. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 36(11), 1514–1528. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167210385360

-

Hall, S. (1997). Cultural identity and diaspora. In K. Woodward (Ed.), Identity and difference (pp. 392–403).

-

Klappenabach, A. (2022, January 7). The 12 most spoken languages in the world. Retrieved November 1, 2022, from https://blog.busuu.com/most-spoken-languages-in-the-world/.

-

Pavlenko, A., & Dewaele, J.-M. (2004). Bilingualism & Emotions. Servicio de Publicacións da Universidade de Vigo.

-

Ringberg, T. V., Luna, D., Reihlen, M., & Peracchio, L. A. (2010). Bicultural-bilinguals: The Effect of Cultural Frame Switching on Translation Equivalence. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 10(1), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595809359585

-

Stroinska, M., & Cecchetto, V. (2003). The role of language in re-construction of identity in exile. In Exile, language and identity (pp. 95–105). essay, Peter Lang.

-

Verkuyten, M., & Pouliasi, K. (2006). Biculturalism and group identification: Cultural Frame Switching in Biculturals With Oppositional Versus Compatible Cultural Identities. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 37(3), 312–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022106286926