Smelling certain aromas, tasting a certain food and seeing certain objects can give us a sense of longing for home. It can make us feel nostalgic. But what is the psychological purpose of nostalgia? How does it help us? If nostalgia allows us to reminisce about wonderful memories, what happens when we lose our memory? Do we lose our sense of home?

Smelling certain aromas, tasting a certain food and seeing certain objects can give us a sense of longing for home. It can make us feel nostalgic. But what is the psychological purpose of nostalgia? How does it help us? If nostalgia allows us to reminisce about wonderful memories, what happens when we lose our memory? Do we lose our sense of home?

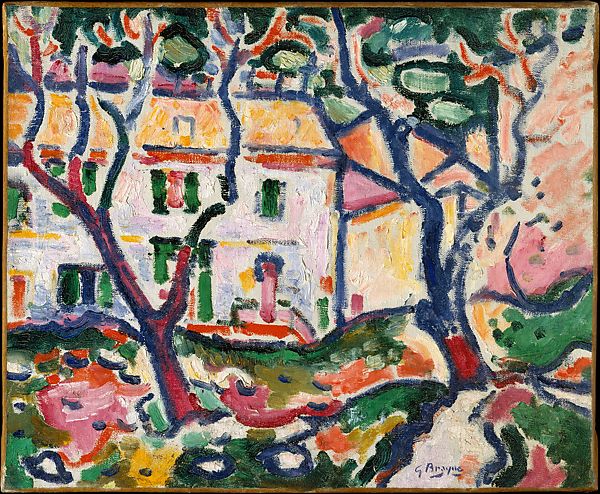

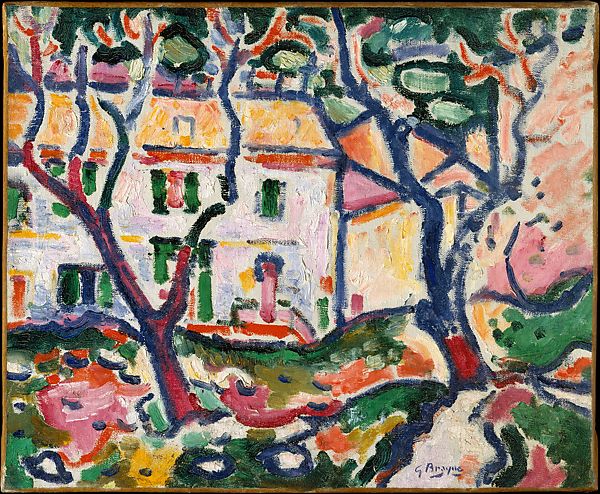

House Behind the Trees by George Braque

When brainstorming about this issue’s theme, home, a wave of different memories I associate with the feeling of home washed over me. Whether it be memories of close friends and family, specific scents, or even the craving for delicious food, the memories gave me a sense of warmth and longing for home, it left me nostalgic.

While now we consider the word nostalgia to be referring to the longing for fond memories of the past, it used to refer to a form of homesickness. In fact, nostalgia was considered to be an unwanted medical condition in the 1870s and Swiss physician Johannes Hoffer attributed it as mania connected to homesickness in Swiss mercenary soldiers (Editors of Merriam Webster, 2018). Even though nostalgia was considered to be a ‘disease’ many years ago, researchers show that it has a lot of positive consequences for our well-being (Vess et al., 2010).

The Psychological Purpose of Nostalgia

Nostalgia allows us to make sense of our identity as it develops through time, and being able to understand and remind ourselves of who we have been and who we are today (Luna & Batcho, 2019). Vess et al. (2010) did experimental research on the benefits of nostalgia. In this study, participants received either negative or positive feedback on their performance and then asked to ponder a nostalgic or a ‘regular’ past experience. Participants who received negative performance feedback and pondered a regular past experience, were more likely to commit a self-serving attribution bias- believing that the failure was a result of the situation rather than ability- in comparison to those who engaged in a nostalgic experience. Those who engaged in a nostalgic experience showed to attribute their failures to their ability rather than the situation. The results of this study can show how nostalgia can serve as a positive resource for the self.

Nostalgia comes in many types and forms. One specific type of nostalgia is ‘reflective’ nostalgia, in which a person experiences nostalgia as idealising a moment of the past (McDonald, 2016). After engaging in reflective nostalgia, people have shown to feel more socially confident, valued, loved and positive about forming strong relationships (Routledge, 2019). Nostalgia also plays a key role in enforcing deep family and cultural relationships and has shown to be vital to social connectedness and pro-social emotion (Luna & Batcho, 2019). While the disconnectedness among people is gradually increasing in individualistic societies, nostalgia has shown to play a key role in bringing people together. Shared nostalgia has increased as media has become a more core aspect of our lives, all it takes is a quick share with the phrase ‘remember this’ or ‘do you remember’ to transport us back to a time of the past. Positive emotions that are tied to nostalgic memories are contagious and this could explain why the sharing of such memories brings people closer together. On the other hand, this also explains why people can be disinterested when someone is sharing a story they do not have nostalgic value in.

As research shows that nostalgia has such great psychological purposes to enhance our well-being, it left me pondering the question, what happens when we do not have the memories to experience nostalgia?

“I spend so much time reminiscing memories of family, friends, and home, I cannot imagine what it must be like to lose the memory of a home itself.”

An Unrecognizable Home

For the cover of this issue, I had asked my fellow editors to send me a list of things they associated with ‘home’. I was able to sense the excitement and nostalgia they had felt as I related to a few things they had mentioned. But if we feel so nostalgic for aspects of home that may be out of reach, what happens when our memories are distorted or even lost?

Delving further into this train of thought, I had stumbled upon a poem featured in Anne M Evans’ poetry anthology ‘Forgetting Home: Poems about Alzheimer’s’. It is Barbara Crooker’s ekphrastic poem, ‘House Behind the Trees 1906-7’, inspired by a painting of the same name by George Braque (The Ekphrastic Review, 2018):

I want to go home my friend’s mother says

over and over, even though this is the house

she’s lived in for fifty-some years. Alzheimer’s,

dementia, same old story: they want to go home.

I wish I could send them to this house behind the blue

trees, with its solid flattened space, bright primaries outlined

in bold strokes of cobalt. The rest of the colours run away

with themselves, the spectrum as playground. Wouldn’t

we want this, too, a return to childhood’s box of Crayolas,

coloring the roof yellow if we felt like it, the sky, sea-green,

with clouds swimming by like a school of fish. We could splash

pink wherever we wanted, eat marshmallows for dinner,

yell oley oley in free as the shadows twist and lengthen.

Aside from the wonderful imagery and my personal memories of childhood Crayola masterpieces, the first four lines of this poem rang in my mind. I spend so much time reminiscing memories of family, friends, and home, I cannot imagine what it must be like to lose the memory of a home itself. This poem also reminded me of another type of nostalgia that is very different to ‘reflective’ nostalgia- ‘restorative’ nostalgia. ‘Restorative’ nostalgia- also known as return home nostalgia- is a nostalgic experience that seeks to reconstruct and relive the past (McDonald, 2016).

Of course, it is debated whether home is a physical place, a feeling, or a person, but with fragmented memory, all possible definitions of home are affected. Hence, my search into how nostalgia could be a useful construct to explore for Alzheimer’s and dementia treatment began.

“Nostalgia allows us to reminisce on the wonderful moments of the past, and show how far we’ve come for a better tomorrow.”

Evoking Nostalgia in Alzheimer’s Patients

A treatment that has been used in treating Alzheimer’s and dementia is music therapy. Extensive research has been done into the effectiveness of this intervention on cognitive functions, behavior and its consequences for memory in such patients. One of the reasons why this treatment has become prevalent is due to the evidence suggesting that memory of music remains intact in people with Alzheimer’s despite the rapid cognitive decline (Cuddy et al., 2012, as cited in Leggieri et al., 2019). Since the act of listening to music is registered as implicit memory, the kind of memory that does not require conscious retrieval, it can be inherently connected to certain memories and thus remain intact (Heshmat, 2021).

Music and nostalgia are interlinked as it has the capacity to trigger the remembrance of specific events, people, emotions and places (Davidson & Garrido, 2014 as cited in Stevens, 2015). Music’s capacity is most effective when it is linked to autobiographical memories, especially those from one’s youth and adolescence, known as the ‘reminiscence bump’. Depending on the type of music, it has been theorized to evoke positive emotional responses which in turn can activate the parasympathetic or sympathetic nervous system, allowing the alleviation of some neuropsychological symptoms (Peck et al., 2016 as cited in Leggieri et al., 2019). The organisation ‘Music and Memory’ utilises this treatment and brings music to patients in nursing homes and other care organisations to ‘renew meaning and connection in their lives’.

However, music is not the only art form that can be used in therapy for Alzheimer’s and dementia patients, visual art can also be effective in this regard. Although this type of therapy does not play on nostalgia, therapy involving the production of visual art can allow Alzheimer’s disease or dementia patients to have improved neuropsychiatric symptoms (Chancellor et al., 2014). In case studies, the use of art therapy has shown to engage the attention, improve self esteem, social behavior and provide pleasure to patients- hence, improve their quality of life little by little.

Despite nostalgia being considered as an unwanted and abnormal condition long ago, research now suggests that it has an immensely positive psychological purpose for the self, as well as socially. Nostalgia allows us to reminisce on the wonderful moments of the past, and show how far we’ve come for a better tomorrow. Though nostalgic experience is heavily grounded in being able to retrieve memories, those with distorted or lost memory, such as Alzheimer’s or dementia patients, are still able to use the wonders of nostalgia through various means such as music to experience its positive benefits. <<

References

-Chancellor, B., Duncan, A., & Chatterjee, A. (2014). Art Therapy for Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 39(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-131295

-Editors of Merriam-Webster. (2018, February 23). Nostalgia Isn’t What It Used to Be. The Merriam-Webster.Com Dictionary.

-Heshmat, S. (2021, September 14). Why Does Music Evoke Memories? Psychology Today.

-Leggieri, M., Thaut, M. H., Fornazzari, L., Schweizer, T. A., Barfett, J., Munoz, D. G., & Fischer, C. E. (2019). Music Intervention Approaches for Alzheimer’s Disease: A Review of the Literature. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2019.00132

-Luna, K. (Hosts). (2019, November). Does Nostalgia Have a Psychological Purpose? (No. 93) [Audio podcast episode]. In Speaking of Psychology. American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/research/action/speaking-of-psychology/nostalgia

-McDonald, H. (2016, June 23). The Two Faces of Nostalgia. Psychology Today.

-Routledge, C. (2019, May 21). Nostalgia Reveals the Importance of Family and Close Relationships. Institute for Family Studies.

-Stevens, C. J. (2015). Is memory for music special? Memory Studies, 8(3), 263–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750698015584873

-The Ekphrastic Review. (2018, May 30). House Behind the Trees, 1906–07, by Barbara Crooker.

When brainstorming about this issue’s theme, home, a wave of different memories I associate with the feeling of home washed over me. Whether it be memories of close friends and family, specific scents, or even the craving for delicious food, the memories gave me a sense of warmth and longing for home, it left me nostalgic.

While now we consider the word nostalgia to be referring to the longing for fond memories of the past, it used to refer to a form of homesickness. In fact, nostalgia was considered to be an unwanted medical condition in the 1870s and Swiss physician Johannes Hoffer attributed it as mania connected to homesickness in Swiss mercenary soldiers (Editors of Merriam Webster, 2018). Even though nostalgia was considered to be a ‘disease’ many years ago, researchers show that it has a lot of positive consequences for our well-being (Vess et al., 2010).

The Psychological Purpose of Nostalgia

Nostalgia allows us to make sense of our identity as it develops through time, and being able to understand and remind ourselves of who we have been and who we are today (Luna & Batcho, 2019). Vess et al. (2010) did experimental research on the benefits of nostalgia. In this study, participants received either negative or positive feedback on their performance and then asked to ponder a nostalgic or a ‘regular’ past experience. Participants who received negative performance feedback and pondered a regular past experience, were more likely to commit a self-serving attribution bias- believing that the failure was a result of the situation rather than ability- in comparison to those who engaged in a nostalgic experience. Those who engaged in a nostalgic experience showed to attribute their failures to their ability rather than the situation. The results of this study can show how nostalgia can serve as a positive resource for the self.

Nostalgia comes in many types and forms. One specific type of nostalgia is ‘reflective’ nostalgia, in which a person experiences nostalgia as idealising a moment of the past (McDonald, 2016). After engaging in reflective nostalgia, people have shown to feel more socially confident, valued, loved and positive about forming strong relationships (Routledge, 2019). Nostalgia also plays a key role in enforcing deep family and cultural relationships and has shown to be vital to social connectedness and pro-social emotion (Luna & Batcho, 2019). While the disconnectedness among people is gradually increasing in individualistic societies, nostalgia has shown to play a key role in bringing people together. Shared nostalgia has increased as media has become a more core aspect of our lives, all it takes is a quick share with the phrase ‘remember this’ or ‘do you remember’ to transport us back to a time of the past. Positive emotions that are tied to nostalgic memories are contagious and this could explain why the sharing of such memories brings people closer together. On the other hand, this also explains why people can be disinterested when someone is sharing a story they do not have nostalgic value in.

As research shows that nostalgia has such great psychological purposes to enhance our well-being, it left me pondering the question, what happens when we do not have the memories to experience nostalgia?

“I spend so much time reminiscing memories of family, friends, and home, I cannot imagine what it must be like to lose the memory of a home itself.”

An Unrecognizable Home

For the cover of this issue, I had asked my fellow editors to send me a list of things they associated with ‘home’. I was able to sense the excitement and nostalgia they had felt as I related to a few things they had mentioned. But if we feel so nostalgic for aspects of home that may be out of reach, what happens when our memories are distorted or even lost?

Delving further into this train of thought, I had stumbled upon a poem featured in Anne M Evans’ poetry anthology ‘Forgetting Home: Poems about Alzheimer’s’. It is Barbara Crooker’s ekphrastic poem, ‘House Behind the Trees 1906-7’, inspired by a painting of the same name by George Braque (The Ekphrastic Review, 2018):

I want to go home my friend’s mother says

over and over, even though this is the house

she’s lived in for fifty-some years. Alzheimer’s,

dementia, same old story: they want to go home.

I wish I could send them to this house behind the blue

trees, with its solid flattened space, bright primaries outlined

in bold strokes of cobalt. The rest of the colours run away

with themselves, the spectrum as playground. Wouldn’t

we want this, too, a return to childhood’s box of Crayolas,

coloring the roof yellow if we felt like it, the sky, sea-green,

with clouds swimming by like a school of fish. We could splash

pink wherever we wanted, eat marshmallows for dinner,

yell oley oley in free as the shadows twist and lengthen.

Aside from the wonderful imagery and my personal memories of childhood Crayola masterpieces, the first four lines of this poem rang in my mind. I spend so much time reminiscing memories of family, friends and home, I cannot imagine what it must be like to lose memory of a home itself. This poem also reminded me of another type of nostalgia that is very different to ‘reflective’ nostalgia- ‘restorative’ nostalgia. ‘Restorative’ nostalgia- also known as return home nostalgia- is a nostalgic experience that seeks to reconstruct and relive the past (McDonald, 2016).

Of course, it is debated whether home is a physical place, a feeling or a person, but with fragmented memory all possible definitions of home are affected. Hence, my search into how nostalgia could be a useful construct to explore for Alzheimer’s and dementia treatment began.

“Nostalgia allows us to reminisce on the wonderful moments of the past, and show how far we’ve come for a better tomorrow.”

Evoking Nostalgia in Alzheimer’s Patients

A treatment that has been used in treating Alzheimer’s and dementia is music therapy. Extensive research has been done into the effectiveness of this intervention on cognitive functions, behavior and its consequences for memory in such patients. One of the reasons why this treatment has become prevalent is due to the evidence suggesting that memory of music remains intact in people with Alzheimer’s despite the rapid cognitive decline (Cuddy et al., 2012, as cited in Leggieri et al., 2019). Since the act of listening to music is registered as implicit memory, the kind of memory that does not require conscious retrieval, it can be inherently connected to certain memories and thus remain intact (Heshmat, 2021).

Music and nostalgia are interlinked as it has the capacity to trigger the remembrance of specific events, people, emotions and places (Davidson & Garrido, 2014 as cited in Stevens, 2015). Music’s capacity is most effective when it is linked to autobiographical memories, especially those from one’s youth and adolescence, known as the ‘reminiscence bump’. Depending on the type of music, it has been theorized to evoke positive emotional responses which in turn can activate the parasympathetic or sympathetic nervous system, allowing the alleviation of some neuropsychological symptoms (Peck et al., 2016 as cited in Leggieri et al., 2019). The organisation ‘Music and Memory’ utilises this treatment and brings music to patients in nursing homes and other care organisations to ‘renew meaning and connection in their lives’.

However, music is not the only art form that can be used in therapy for Alzheimer’s and dementia patients, visual art can also be effective in this regard. Although this type of therapy does not play on nostalgia, therapy involving the production of visual art can allow Alzheimer’s disease or dementia patients to have improved neuropsychiatric symptoms (Chancellor et al., 2014). In case studies, the use of art therapy has shown to engage the attention, improve self esteem, social behavior and provide pleasure to patients- hence, improve their quality of life little by little.

Despite nostalgia being considered as an unwanted and abnormal condition long ago, research now suggests that it has an immensely positive psychological purpose for the self, as well as socially. Nostalgia allows us to reminisce on the wonderful moments of the past, and show how far we’ve come for a better tomorrow. Though nostalgic experience is heavily grounded in being able to retrieve memories, those with distorted or lost memory, such as Alzheimer’s or dementia patients, are still able to use the wonders of nostalgia through various means such as music to experience its positive benefits. <<