For centuries, it was believed that humans made decisions on the basis of maximizing value. Recent theories and evidence show that this is most likely false. It is mainly the field of behavioral economics that demonstrates how superficial appearance can dictate our decisions.

For centuries, it was believed that humans made decisions on the basis of maximizing value. Recent theories and evidence show that this is most likely false. It is mainly the field of behavioral economics that demonstrates how superficial appearance can dictate our decisions.

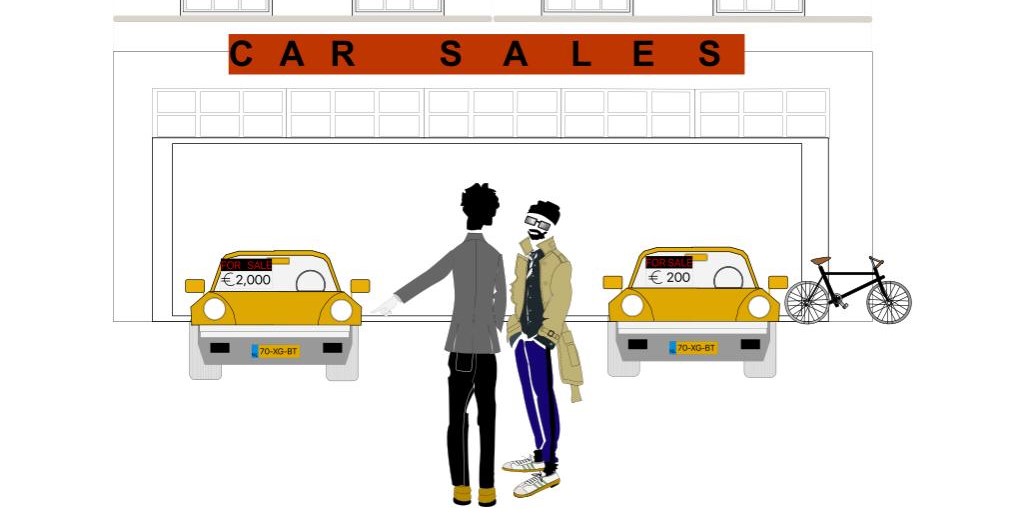

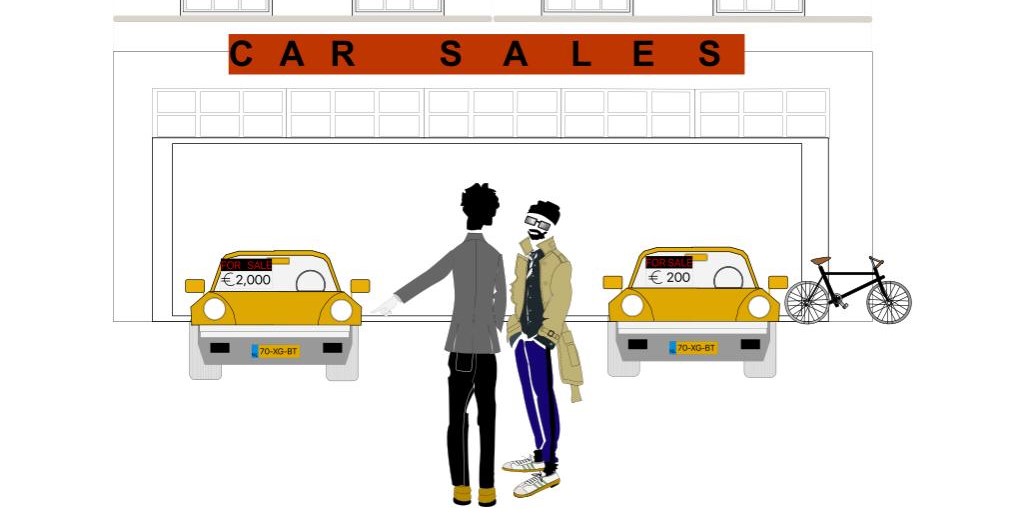

Illustration: Marta Narbona Calvo

Imagine you are cycling home from Roeterseiland Campus. Suddenly you remember you don’t have much food at home and decide to stop at Albert Heijn. While you are walking around the supermarket, you encounter an interesting sign: ‘ten percent off Barilla spaghetti, limited to twelve per person.’ ‘That’s weird,’ you think, ‘no one would buy that amount of spaghetti.’ You grab three packs and continue shopping. As you head home, you realize it is the first time you bought more than one pack of spaghetti, even though Barilla spaghetti had been on sale before. You are perplexed and wonder what just happened.

In this hypothetical situation you have behaved irrationally. Presented with the same decision you faced in previous visits to the supermarket, you chose a different option. The value (i.e. how well it suits your needs) of the spaghetti has not changed. But the appearance of the decision (i.e. the information presented to you, in this case the sign) has changed. This is a phenomenon that conventional economics cannot predict. Economists need the help of psychologists, leading to the birth of behavioral economics. I will now explore two important contributions from this field and conclude by pointing out some interesting implications.

“Economists need the help of psychologists, leading to the birth of behavioral economics”

Let’s begin with explaining what happened to the hypothetical ‘you’ in the supermarket. In this case, we have witnessed a phenomenon called anchoring. This is defined by Kahneman as the consideration of ‘a particular value for an unknown quantity before estimating that quantity’ (Kahneman, 2011). He found out that this first quantity will affect the succeeding estimation. As an example, imagine a person is asked ‘whether Gandhi was more than 114 years old when he died’ and a second one if ‘Gandhi was older than 35 when he died.’ If later they are requested to estimate Gandhi’s age at death, the first person will probably answer a higher number than the second one (Kahneman, 2011). The concept of anchoring was applied to decision making in a field research by Wansink, Kent & Hoch (1998). They created a scenario similar to the one described in the hypothetical supermarket story. They applied a twelve percent discount on Campbell’s Soup in three supermarkets. In each of them, the following signs were placed for some time: ‘no limit per person;’ ‘limit of 4 per person’ and ‘limit of twelve per person.’ The average number of cans bought by customers during each condition was 3.3, 3.6 and 7, respectively. The presentation of an arbitrary number before the customer estimated the right amount of soup they needed affected their estimation. Without any change in the value of Campbell’s Soup, appearance (i.e. information presented) affects customers’ decisions.

Another mechanism that affects our decision making is framing. In order to understand this better, let us imagine that we are two friends who were just accepted to study at the UvA. As we are international students, the university sends us information about their housing services. My mail says: ‘pay before June and get a fifteen percent discount on your fee’. Yours says: ‘pay before June or you will get a fifteen percent penalty on your fee.’ The next time we talk, I tell you that I forgot to pay early. You, on the other hand, paid before June as you didn’t want to get a penalty. We both had to decide how early to pay and the value (i.e. the amount of money saved) of paying early was the same both of us. Did you pay early because of your personality traits, or did the difference in the mails have something to do with it? This question was posed by Gächter et al. (2009), using a similar situation regarding the fee to participate in the Economic Science Association meeting of 2006. In this field study, a random half of the participants received the ‘discount mail’, and the other half the ‘penalty mail’. The percentage of junior participants (i.e. students) who paid early was 67 and 93 percent, respectively. The effect the mail had on how early the students paid is called framing, ‘changes of preferences […] caused by inconsequential variations in the wording of a choice problem’ (Kahneman, 2011). In this case, presenting the fifteen percent difference in the price as a loss rather than a gain increased the preference of participants for paying early. This is explained by ‘loss aversion’: humans suffer more from losing than from not gaining (Kahneman, 2011). All students had to choose between paying a smaller amount earlier or a greater amount later. Nonetheless, the way the option was presented influenced their decision.

“Humans suffer more from losing than from not gaining”

As we have seen through the Barilla spaghetti and the UvA email examples, by changing superfluous information about a decision, customers and students change their behavior in predictable ways. By understanding that the mind works using heuristics (i.e. rules-of-thumb) and is conditioned by biases, it is possible to influence behavior towards desired directions. You now might be thinking about marketing. That is a possible application of this knowledge. It consists of steering customer’s behavior towards the direction most profitable for your business. You may also think about governments and policy making. If you want to make people’s behavior less violent, less dangerous or less pollutant, why not change the appearance of the options to improve their decisions? Finally, even if you have less ambitious aspirations, like not getting tricked by Albert Heijn sales on Barilla spaghetti, remember that when it comes to decision making: it is about appearance.

References

– Gächter, S., Orzen, H., Renner, E., & Starmer, C. (2009). Are experimental economists prone to framing effects? A natural field experiment. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 70(3), 443–446.

– Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. p.119, 271, 282.

– Wansink, B., Kent, R. J., & Hoch, S. J. (1998). An anchoring and adjustment model of purchase quantity decisions. Journal of Marketing Research (1998), 71-81.

Imagine you are cycling home from Roeterseiland Campus. Suddenly you remember you don’t have much food at home and decide to stop at Albert Heijn. While you are walking around the supermarket, you encounter an interesting sign: ‘ten percent off Barilla spaghetti, limited to twelve per person.’ ‘That’s weird,’ you think, ‘no one would buy that amount of spaghetti.’ You grab three packs and continue shopping. As you head home, you realize it is the first time you bought more than one pack of spaghetti, even though Barilla spaghetti had been on sale before. You are perplexed and wonder what just happened.

In this hypothetical situation you have behaved irrationally. Presented with the same decision you faced in previous visits to the supermarket, you chose a different option. The value (i.e. how well it suits your needs) of the spaghetti has not changed. But the appearance of the decision (i.e. the information presented to you, in this case the sign) has changed. This is a phenomenon that conventional economics cannot predict. Economists need the help of psychologists, leading to the birth of behavioral economics. I will now explore two important contributions from this field and conclude by pointing out some interesting implications.

“Economists need the help of psychologists, leading to the birth of behavioral economics”

Let’s begin with explaining what happened to the hypothetical ‘you’ in the supermarket. In this case, we have witnessed a phenomenon called anchoring. This is defined by Kahneman as the consideration of ‘a particular value for an unknown quantity before estimating that quantity’ (Kahneman, 2011). He found out that this first quantity will affect the succeeding estimation. As an example, imagine a person is asked ‘whether Gandhi was more than 114 years old when he died’ and a second one if ‘Gandhi was older than 35 when he died.’ If later they are requested to estimate Gandhi’s age at death, the first person will probably answer a higher number than the second one (Kahneman, 2011). The concept of anchoring was applied to decision making in a field research by Wansink, Kent & Hoch (1998). They created a scenario similar to the one described in the hypothetical supermarket story. They applied a twelve percent discount on Campbell’s Soup in three supermarkets. In each of them, the following signs were placed for some time: ‘no limit per person;’ ‘limit of 4 per person’ and ‘limit of twelve per person.’ The average number of cans bought by customers during each condition was 3.3, 3.6 and 7, respectively. The presentation of an arbitrary number before the customer estimated the right amount of soup they needed affected their estimation. Without any change in the value of Campbell’s Soup, appearance (i.e. information presented) affects customers’ decisions.

Another mechanism that affects our decision making is framing. In order to understand this better, let us imagine that we are two friends who were just accepted to study at the UvA. As we are international students, the university sends us information about their housing services. My mail says: ‘pay before June and get a fifteen percent discount on your fee’. Yours says: ‘pay before June or you will get a fifteen percent penalty on your fee.’ The next time we talk, I tell you that I forgot to pay early. You, on the other hand, paid before June as you didn’t want to get a penalty. We both had to decide how early to pay and the value (i.e. the amount of money saved) of paying early was the same both of us. Did you pay early because of your personality traits, or did the difference in the mails have something to do with it? This question was posed by Gächter et al. (2009), using a similar situation regarding the fee to participate in the Economic Science Association meeting of 2006. In this field study, a random half of the participants received the ‘discount mail’, and the other half the ‘penalty mail’. The percentage of junior participants (i.e. students) who paid early was 67 and 93 percent, respectively. The effect the mail had on how early the students paid is called framing, ‘changes of preferences […] caused by inconsequential variations in the wording of a choice problem’ (Kahneman, 2011). In this case, presenting the fifteen percent difference in the price as a loss rather than a gain increased the preference of participants for paying early. This is explained by ‘loss aversion’: humans suffer more from losing than from not gaining (Kahneman, 2011). All students had to choose between paying a smaller amount earlier or a greater amount later. Nonetheless, the way the option was presented influenced their decision.

“Humans suffer more from losing than from not gaining”

As we have seen through the Barilla spaghetti and the UvA email examples, by changing superfluous information about a decision, customers and students change their behavior in predictable ways. By understanding that the mind works using heuristics (i.e. rules-of-thumb) and is conditioned by biases, it is possible to influence behavior towards desired directions. You now might be thinking about marketing. That is a possible application of this knowledge. It consists of steering customer’s behavior towards the direction most profitable for your business. You may also think about governments and policy making. If you want to make people’s behavior less violent, less dangerous or less pollutant, why not change the appearance of the options to improve their decisions? Finally, even if you have less ambitious aspirations, like not getting tricked by Albert Heijn sales on Barilla spaghetti, remember that when it comes to decision making: it is about appearance. <<