“Half of us will be gone by next semester”, my friend sneered, his gaze wandering along the rows of first years awaiting their very first lecture “Let’s bet who”.

The drop-out discussion kept returning to our conversations. It seemed that a staggering number of students dropped out of the impossibly difficult psychology program, year after year, until finally, only the most brilliant and the iron-willed remained. Three years from now, the last two psychology students would be standing on some sad stage, clutching their diplomas and weeping for their lost comrades. This is Sparta.

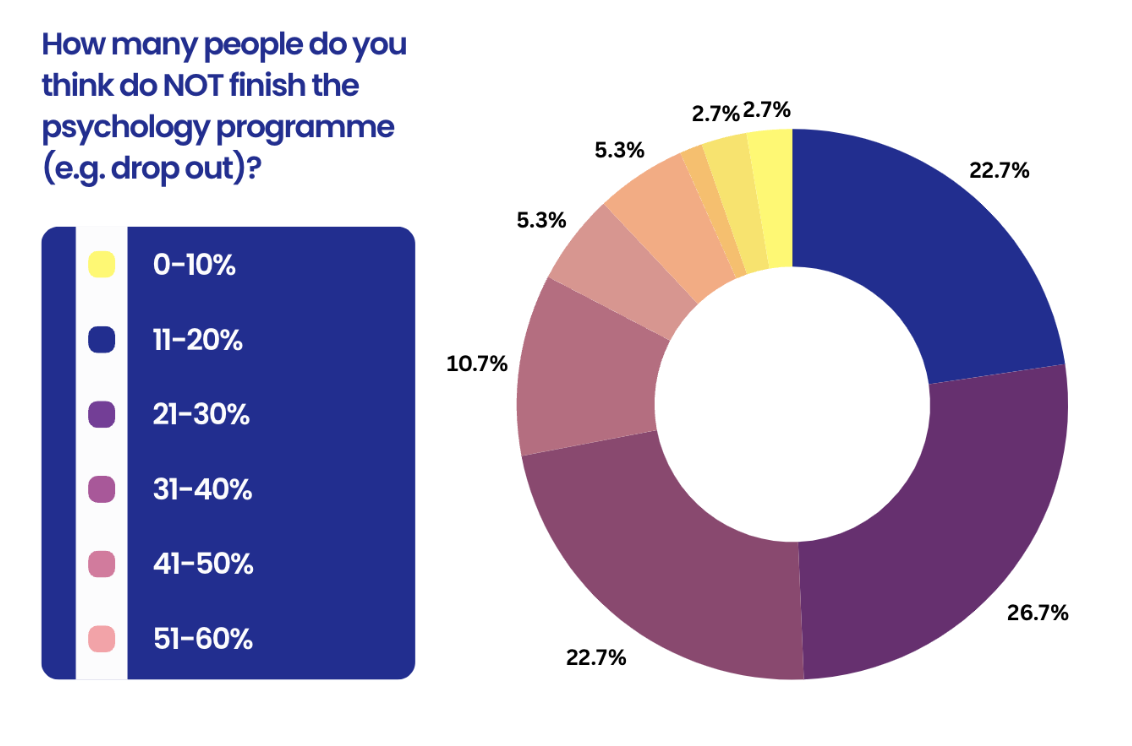

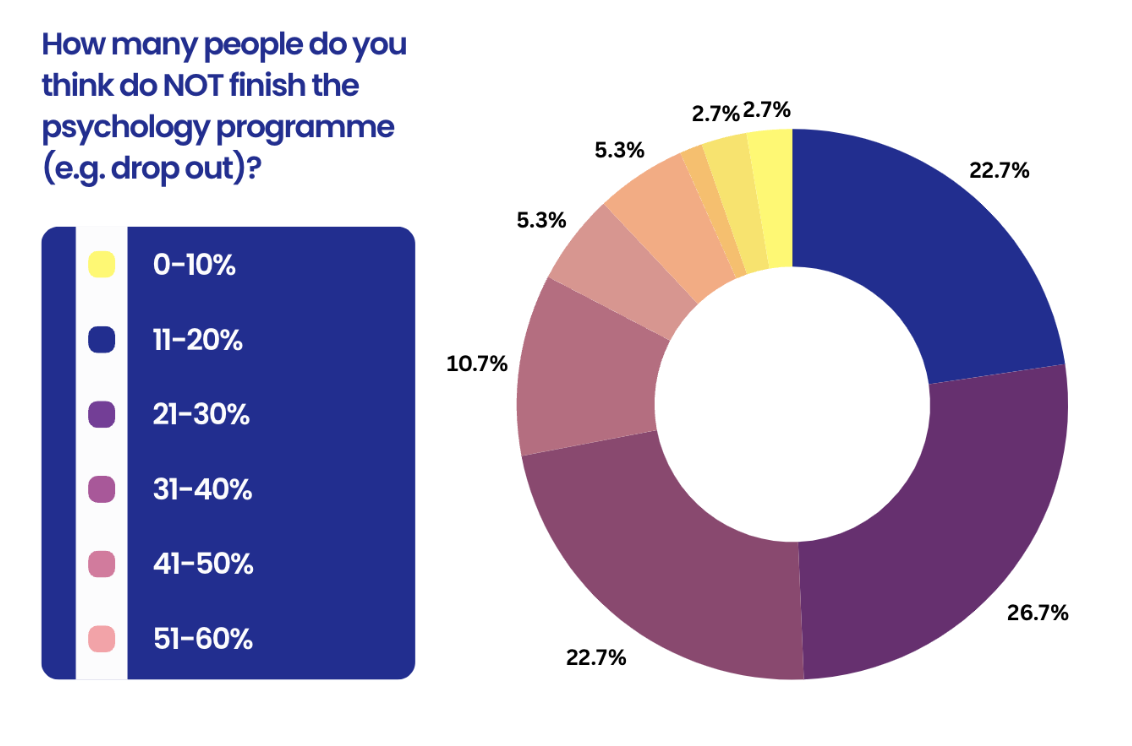

How many students actually believe this? To find out, I created a Google form which I sent into the first years’ WhatsApp group chat. 75 students gave the following answers:

Averaging over these beliefs, students in the current first year of the psychology program believe that around 33% of us will never finish their studies.

In short: enough dread to fill some pages. So, I emailed and interviewed my way through the depths of the UvA’s administrative system, which has been making exactly none of the data they have on this subject public. In the following sections, I will discuss the actual drop-out rates. How do we compare to other universities? Just how hard is the psychology program really, and how does the UvA address its students’ difficulties?

Are we all doomed?

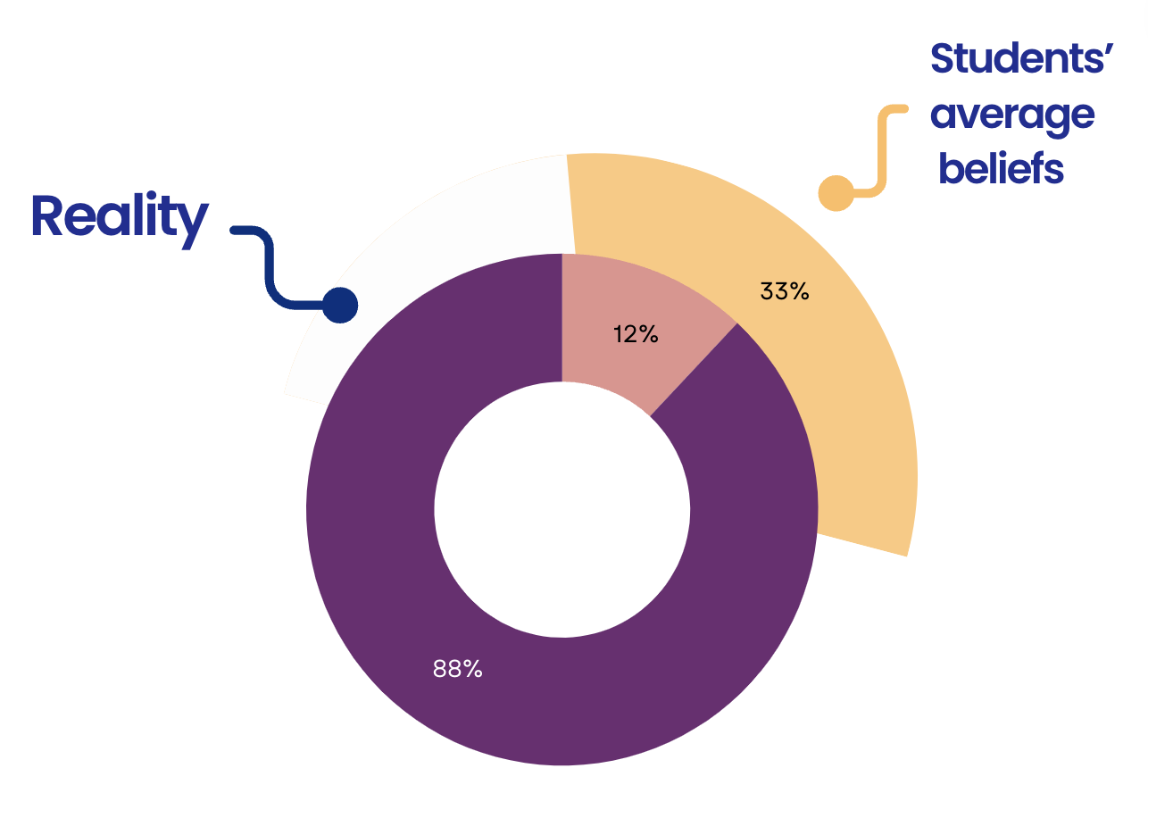

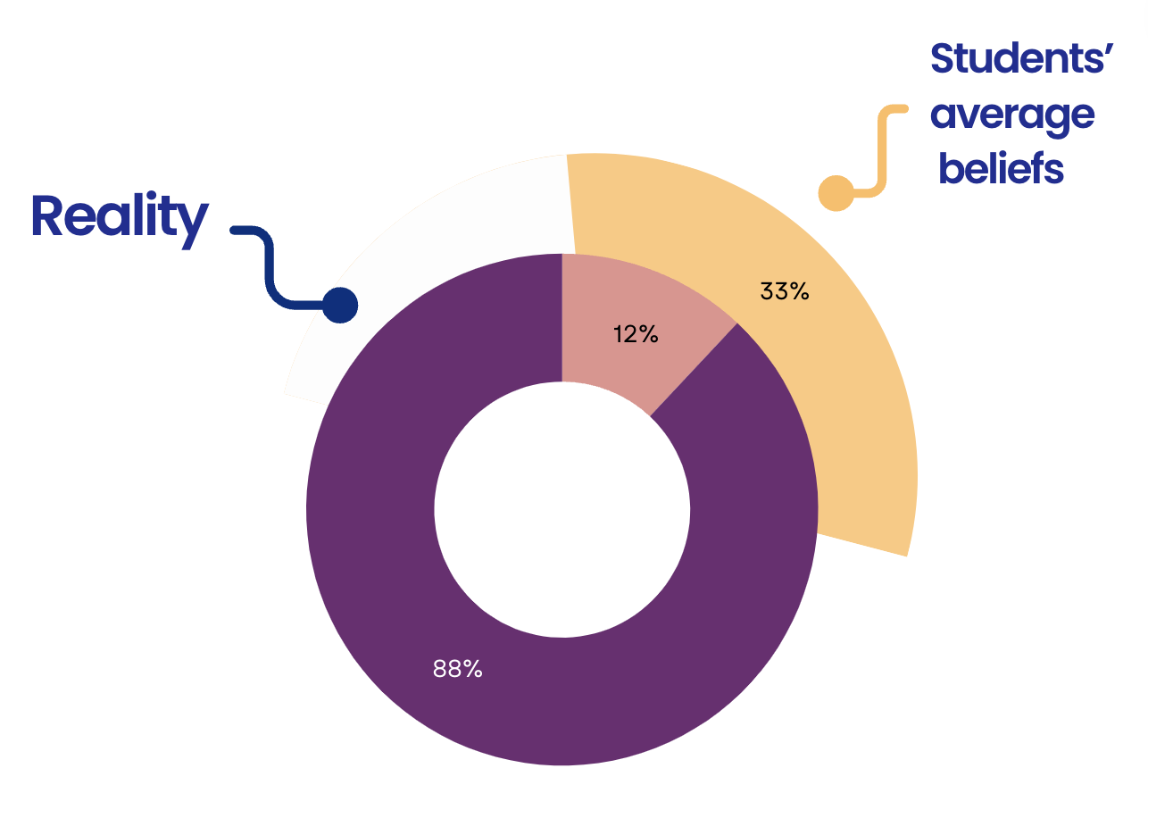

Put plainly, no. Not at all. In fact, most of us are likely going to successfully obtain our degree. It took only a single email to the UvAs education desk to find out: In the year 2022-23, only 9% of first year psychology students dropped out of the program. Looking at students who began their studies in 2018, only 12% of them had not obtained their diploma after five years. So just how wrong were students about the dropout rates? Since only 25% of us believe that the dropout rate is between 0 and 20%, this means that 75% of students overestimate the dropout rates!

Assuming that the dropout rate in the UvA’s psychology program is around 12%, is this a high number? In the rest of the Netherlands, the mean dropout rate across all subjects is around 11.8% (Aina et al., 2022). This makes the UvA’s dropout rates average. Comparisons to the rest of Europe are difficult to make, since little data is available and dropout rates range from 3-4% in Bulgaria up to 40% in Croatia (Kottmann et al., 2015). In the USA, however, dropout rates are around 24% for full-time students (National Center for Education Statistics, 2024). This is twice the dropout rate of that at the UvA! If anything, the UvA therefore seems to have dropout rates that are normal, or even quite low.

Though reassuring, these numbers left me wondering. Why does such a rumour exist? Surely, part of the answer lies in the fact that the UvA does not make this data public. Students are simply left to guess, or to rely on numbers that a friend of a friend found in his beer glass at a post-exam borrel three months prior. My personal guess, however, is that the program is overwhelming enough to make you believe such rumours.

Not doomed, but struggling

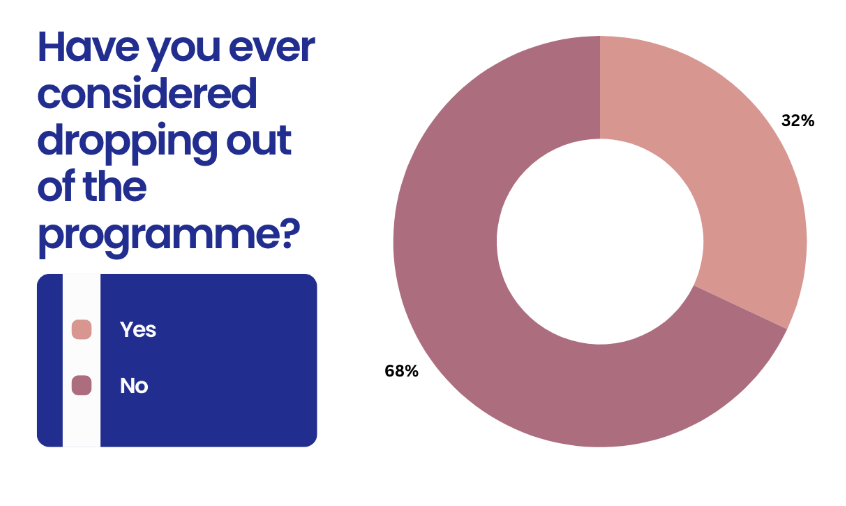

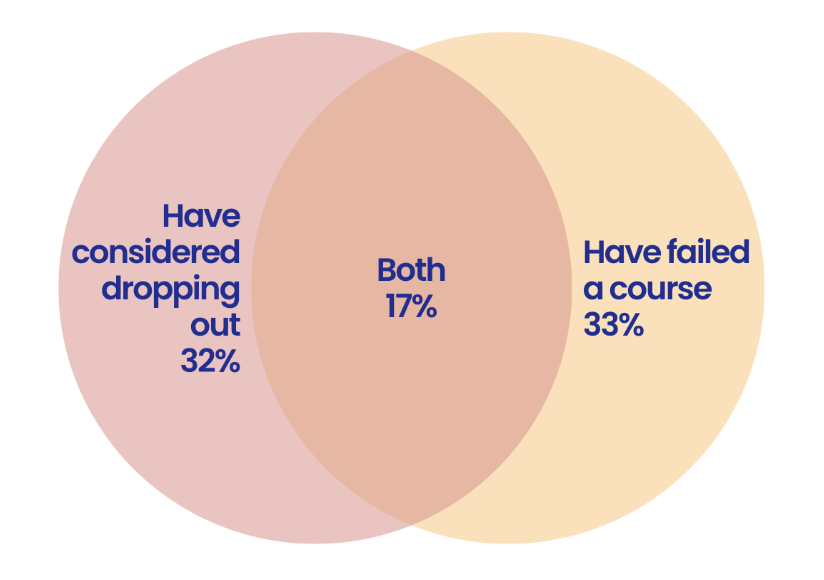

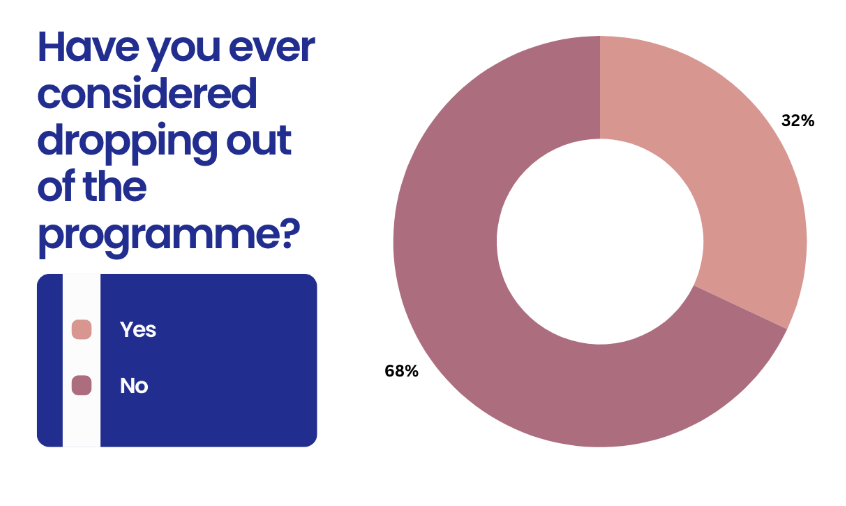

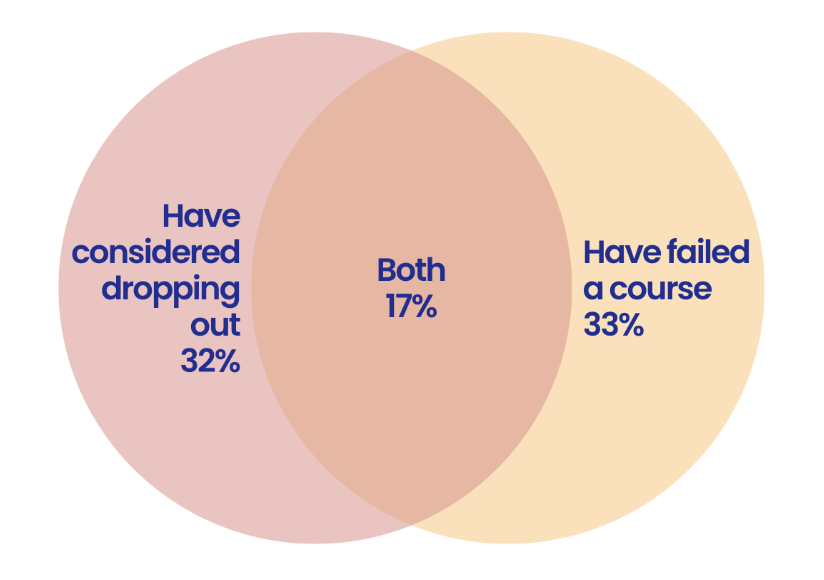

Only nine percent of us drop out. Yet a third of us have considered doing so at some point. In the aforementioned Google form, I asked students the question “Have you ever considered dropping out of the program?”. Bear in mind that these were mostly students who had only just begun the second half of their first semester. Most of our exam anxiety and deadline dread still lie before, not behind us. Nevertheless, 32% of students replied that they had, indeed, considered quitting before. Furthermore, 33% of these students had failed at least one course so far. As an aside, these were not entirely the same students.

So far, the drop-out statistics have been rather uplifting. Most students finish the program successfully and in this regard, the UvA compares well to the rest of the world. No need to worry. However, though only 9% drop out of the program in the first year, it is also only 55% percent of psychology students who manage to finish the program in the specified three years. The UvA offers a course in which most students successfully obtain their diploma. But it is also a course in which barely more than half of students manage to accomplish everything that is expected of them within the timeframe in which it is expected. Who, then, made it this tough?

Staying longer means paying longer?

As nicely illustrated by the results of the aforementioned survey, neither me nor the other students had any knowledge about the dropout rates at all. This did not keep us from hypothesising why they were so high. “Well, if students fail, they’ll just keep paying those student fees”, my friend commented with a sly grin. Scandalous.

Yet when I interviewed Sonja Houtkooper from the education desk on this theory, I was only met with amused disbelief. “The UvA is overcrowded”, she laughed out loud. “This is why we have the numerus fixus. If it was just a question of getting the tuition fees, then we’d say ‘come on guys’! So that’s not the case”.

On the contrary, the UvA actively checks its database for students who just cannot seem to finish the program. “We have student advisers who specifically look after these students. To contact them, to try to figure out if there is a problem which we together can fix”. And fix it they will. In my interview with Ms. Houtkooper, I learned that the UvA has an elaborate system of professionals sitting and waiting at desks all around campus and beyond, to help students with just about any conceivable need they might have. Be it the labour market, social adjustment, financial advice or free student counselling – the UvA most likely provides a designated service for it. And if not, the student advisers will show you to a place that does. Moreover, can you guess who gets paid to check in on you twice a week, given that you’re a psychology student in the first year? It is your tutor! “Is that really part of the job?”, I asked when Ms. Houtkooper told me about this. “Yeah, yeah it is! If they notice that you keep showing up late, or they see you have constant red eyes, or… you know? They are on the lookout.” To put it in Ms. Houtkooper’s words: “It might sound cheesy but we care. It’s as simple as that”.

This is the train and once you’re on the train, the train will be running

So we are not being weeded out in some sort of academic hunger games, and we are also not being intentionally lured into an eight-year Bachelor’s program so that the UvA can milk us for eternal study fees. Why, then, is this program so difficult to finish within the designated three years? When I asked Ms. Houtkooper, she answered by telling me about what Dutch university used to be like a few decades ago.

“Previously it was more like: well you’re on the train, and at the first station you get off, and you might hop on again when you feel like it.” Not finishing a program in the time it was designed for seemed to be the norm. Then, perhaps, adding one or two extra readings to a week of studying made little to no difference. If the contents were too much to study in a week, you could simply take another week, and finally another semester. Now, however, “The government has asked us to change the Bachelor’s and the Master’s to be sort of like… Like this is the train and once you’re on the train, the train will be running”. When the psychology program first existed, it may really not have been meant to be finished within strictly three years. To me, these descriptions seemed like we are studying in a changing system. Like the UvA is working to make the contents that used to take four and then some years to study fit into the three years the program is now meant to take.

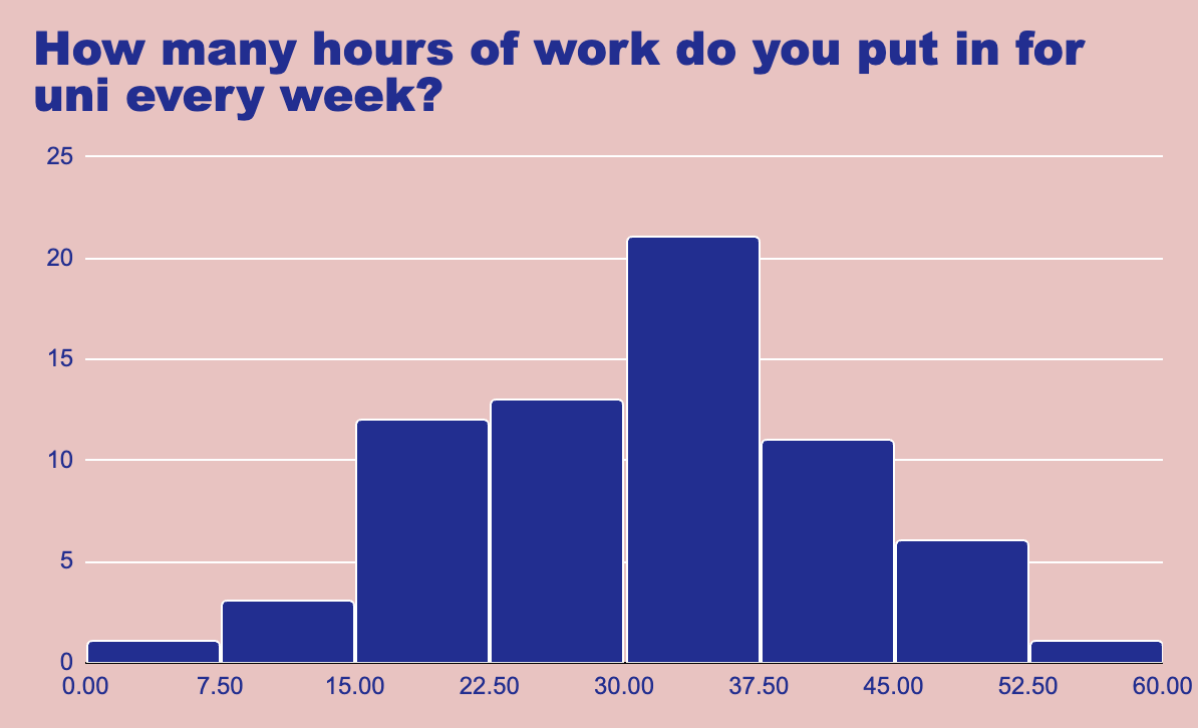

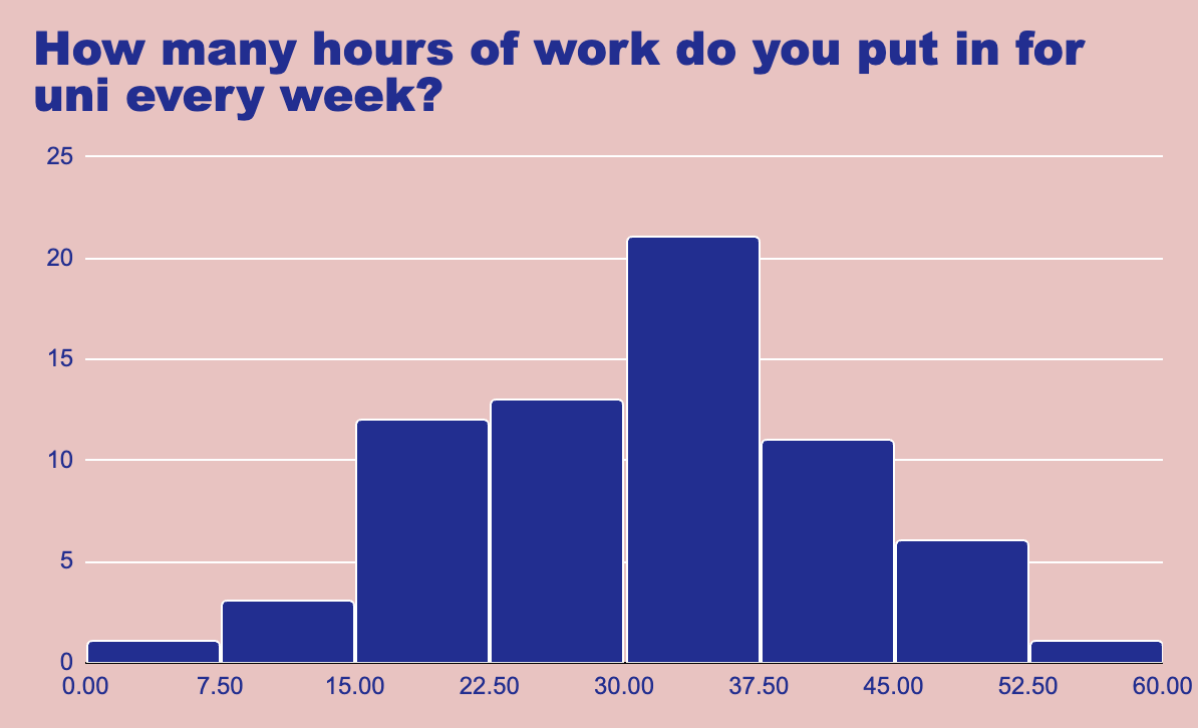

Yet the high rates of failure might not purely be because of the program’s difficulty. A last question that I asked students was “How many hours of work do you put in for uni every week (including attending lectures, tutorials, RWST, self-study etc.)?”. The psychology program is designed as a full time program, taking up to 42 hours of work each week. Students’ answers, however, averaged to only 30 hours a week. Only 12% replied that they put in 42 hours of work or more each week.

In sum, the UvA’s exceptionally high dropout rate is nothing but a rumour. Still, the program is so difficult that only around half of students manage to finish it in three years. If you are feeling overwhelmed, even to the point of considering dropping out of the program, you are not alone. But remember, the odds are in your favour! And if you are ever in need of study advice, counselling or just a friendly borrel, opportunities and resources are almost endless. So hang in there, Spartans rarely surrender.

“Half of us will be gone by next semester”, my friend sneered, his gaze wandering along the rows of first years awaiting their very first lecture “Let’s bet who”.

The drop-out discussion kept returning to our conversations. It seemed that a staggering number of students dropped out of the impossibly difficult psychology program, year after year, until finally, only the most brilliant and the iron-willed remained. Three years from now, the last two psychology students would be standing on some sad stage, clutching their diplomas and weeping for their lost comrades. This is Sparta.

How many students actually believe this? To find out, I created a Google form which I sent into the first years’ WhatsApp group chat. 75 students gave the following answers:

Averaging over these beliefs, students in the current first year of the psychology program believe that around 33% of us will never finish their studies.

In short: enough dread to fill some pages. So, I emailed and interviewed my way through the depths of the UvA’s administrative system, which has been making exactly none of the data they have on this subject public. In the following sections, I will discuss the actual drop-out rates. How do we compare to other universities? Just how hard is the psychology program really, and how does the UvA address its students’ difficulties?

Are we all doomed?

Put plainly, no. Not at all. In fact, most of us are likely going to successfully obtain our degree. It took only a single email to the UvAs education desk to find out: In the year 2022-23, only 9% of first year psychology students dropped out of the program. Looking at students who began their studies in 2018, only 12% of them had not obtained their diploma after five years. So just how wrong were students about the dropout rates? Since only 25% of us believe that the dropout rate is between 0 and 20%, this means that 75% of students overestimate the dropout rates!

Assuming that the dropout rate in the UvA’s psychology program is around 12%, is this a high number? In the rest of the Netherlands, the mean dropout rate across all subjects is around 11.8% (Aina et al., 2022). This makes the UvA’s dropout rates average. Comparisons to the rest of Europe are difficult to make, since little data is available and dropout rates range from 3-4% in Bulgaria up to 40% in Croatia (Kottmann et al., 2015). In the USA, however, dropout rates are around 24% for full-time students (National Center for Education Statistics, 2024). This is twice the dropout rate of that at the UvA! If anything, the UvA therefore seems to have dropout rates that are normal, or even quite low.

Though reassuring, these numbers left me wondering. Why does such a rumour exist? Surely, part of the answer lies in the fact that the UvA does not make this data public. Students are simply left to guess, or to rely on numbers that a friend of a friend found in his beer glass at a post-exam borrel three months prior. My personal guess, however, is that the program is overwhelming enough to make you believe such rumours.

Not doomed, but struggling

Only nine percent of us drop out. Yet a third of us have considered doing so at some point. In the aforementioned Google form, I asked students the question “Have you ever considered dropping out of the program?”. Bear in mind that these were mostly students who had only just begun the second half of their first semester. Most of our exam anxiety and deadline dread still lie before, not behind us. Nevertheless, 32% of students replied that they had, indeed, considered quitting before. Furthermore, 33% of these students had failed at least one course so far. As an aside, these were not entirely the same students.

So far, the drop-out statistics have been rather uplifting. Most students finish the program successfully and in this regard, the UvA compares well to the rest of the world. No need to worry. However, though only 9% drop out of the program in the first year, it is also only 55% percent of psychology students who manage to finish the program in the specified three years. The UvA offers a course in which most students successfully obtain their diploma. But it is also a course in which barely more than half of students manage to accomplish everything that is expected of them within the timeframe in which it is expected. Who, then, made it this tough?

Staying longer means paying longer?

As nicely illustrated by the results of the aforementioned survey, neither me nor the other students had any knowledge about the dropout rates at all. This did not keep us from hypothesising why they were so high. “Well, if students fail, they’ll just keep paying those student fees”, my friend commented with a sly grin. Scandalous.

Yet when I interviewed Sonja Houtkooper from the education desk on this theory, I was only met with amused disbelief. “The UvA is overcrowded”, she laughed out loud. “This is why we have the numerus fixus. If it was just a question of getting the tuition fees, then we’d say ‘come on guys’! So that’s not the case”.

On the contrary, the UvA actively checks its database for students who just cannot seem to finish the program. “We have student advisers who specifically look after these students. To contact them, to try to figure out if there is a problem which we together can fix”. And fix it they will. In my interview with Ms. Houtkooper, I learned that the UvA has an elaborate system of professionals sitting and waiting at desks all around campus and beyond, to help students with just about any conceivable need they might have. Be it the labour market, social adjustment, financial advice or free student counselling – the UvA most likely provides a designated service for it. And if not, the student advisers will show you to a place that does. Moreover, can you guess who gets paid to check in on you twice a week, given that you’re a psychology student in the first year? It is your tutor! “Is that really part of the job?”, I asked when Ms. Houtkooper told me about this. “Yeah, yeah it is! If they notice that you keep showing up late, or they see you have constant red eyes, or… you know? They are on the lookout.” To put it in Ms. Houtkooper’s words: “It might sound cheesy but we care. It’s as simple as that”.

This is the train and once you’re on the train, the train will be running

So we are not being weeded out in some sort of academic hunger games, and we are also not being intentionally lured into an eight-year Bachelor’s program so that the UvA can milk us for eternal study fees. Why, then, is this program so difficult to finish within the designated three years? When I asked Ms. Houtkooper, she answered by telling me about what Dutch university used to be like a few decades ago.

“Previously it was more like: well you’re on the train, and at the first station you get off, and you might hop on again when you feel like it.” Not finishing a program in the time it was designed for seemed to be the norm. Then, perhaps, adding one or two extra readings to a week of studying made little to no difference. If the contents were too much to study in a week, you could simply take another week, and finally another semester. Now, however, “The government has asked us to change the Bachelor’s and the Master’s to be sort of like… Like this is the train and once you’re on the train, the train will be running”. When the psychology program first existed, it may really not have been meant to be finished within strictly three years. To me, these descriptions seemed like we are studying in a changing system. Like the UvA is working to make the contents that used to take four and then some years to study fit into the three years the program is now meant to take.

Yet the high rates of failure might not purely be because of the program’s difficulty. A last question that I asked students was “How many hours of work do you put in for uni every week (including attending lectures, tutorials, RWST, self-study etc.)?”. The psychology program is designed as a full time program, taking up to 42 hours of work each week. Students’ answers, however, averaged to only 30 hours a week. Only 12% replied that they put in 42 hours of work or more each week.

In sum, the UvA’s exceptionally high dropout rate is nothing but a rumour. Still, the program is so difficult that only around half of students manage to finish it in three years. If you are feeling overwhelmed, even to the point of considering dropping out of the program, you are not alone. But remember, the odds are in your favour! And if you are ever in need of study advice, counselling or just a friendly borrel, opportunities and resources are almost endless. So hang in there, Spartans rarely surrender.