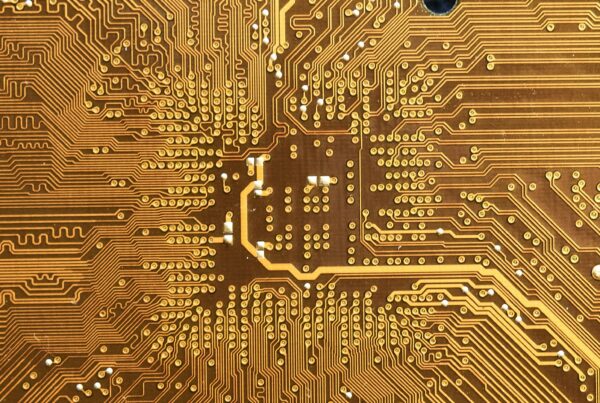

The boom of AI, the surging crisis of climate change, grievous instances of global conflict and unprecedented pandemonium inflicted by an unforeseen virus. This is the world that Generation Z have inherited. How is it shaping their future?

The boom of AI, the surging crisis of climate change, grievous instances of global conflict and unprecedented pandemonium inflicted by an unforeseen virus. This is the world that Generation Z have inherited. How is it shaping their future?

Photo by Greg Bakker on Unsplash

Photo by Greg Bakker on Unsplash

It may come as no surprise then that Gen Z reports the poorest mental health of any generation, according to a 2024 Gallup and Walton Family Foundation report. Although every generation has faced its own challenges, navigating the 21st century lifestyle – an environment that fosters chronically high levels of stress – appears to be an entirely different endeavour. This is especially true given that our nervous systems are adapted for fight-or-flight situations in which the threat eventually passes and cortisol levels subside (Beddington, 2023). Today, however, the pressure life places on us to be engaged in some form of activity round the clock means that we are robbed of the chance to escape, rest and recharge. For one, the endless pursuit for validation and dopamine through social media is linked to addictive behaviour and feelings of low-self worth (McBride, 2023). It does not help that there is an incessant bombardment of information at any given second from an endless supply of sources; friends, family, smartphones, computers and TVs, each placing an overwhelming level of stimulation at our fingertips.

This is particularly the case with Gen Z, who spend an average of seven hours on their phones daily (Ahmed, 2024). On the one hand, this constant connection has enabled remote working, instant communication with loved ones all around the world and the opportunity to stay aware of global affairs. The downside? We are more likely to encounter unexpected and distressing information. We might pick up our phones in order to text our friends but come across news coverage about significant global events such as pandemics, wars, natural disasters, or the impact of climate change. In this way, information begins to consume us, rather than us consuming information. As a result, we experience fatigue, anxiety and impaired concentration. Twenty-three year old Harvard linguistics graduate and content creator Adam Aleksic, known on Instagram as “@etymologynerd” hypothesises that among generation Z, this has led to pessimistic attitudes towards the future which manifests itself through the incorporation of dystopian and apocalyptic language into our day to day vocabulary, including ‘bedrotting’, ‘doom scrolling’, ‘dissociating’ and ‘spiralling’, all of which convey a sense of what has come to be known as disaster fatigue: the effect of being inundated with negative news to the extent that it begins to strain one’s emotions and health (Finn, 2021). Individuals may also experience angst fueled by the sense that we no longer control our own narratives – everything is controlled by political or corporate forces and thus we can’t do anything to stop the events which are causing our disaster fatigue, despite it taking over our screens as well as our minds.

“In what seems to be an effort to romanticise an otherwise chaotic world, older trends are resurfacing.”

The stress experienced by this generation of digital natives can also be attributed to the hustle culture in which they have grown up. Influencers on social media platforms encourage viewers to get up by 5 am, journal, meditate, go to the gym, have a nutritious breakfast and spend some time doing a hobby, all before even starting their work day. While research indeed suggests these are all good practices (Wright, 2023), these videos often imply that they need to accomplish all of these things in order to be successful, contributing to feelings of inadequacy if (or when) one or more of these goals fails to be met. In a similar way, the sponsored advertisement of “must-have” products by influencers could contribute to upward social comparison and feelings of dissatisfaction among those who may be unable to afford these items, possibly stemming from the feeling of being left out. Alongside this, there is the pressure to excel not only academically or career-wise but also in terms of looking a certain way, getting enough sleep, having a social life, learning new skills, investing in stocks and starting one’s own business, all of which seem impossible to do in the same week, let alone day! The incessant grind promoted by hustle culture, combined with the prevailing weltschmerz, a German word capturing the sentiment of weariness at the state of the world (Morgan, 2023), may culminate in burnout among Gen Z, raising the question “What is the purpose of striving when faced with seemingly inevitable adversities?”

Gen Z’s craving for stability and peace in an uncertain and workaholic world is perhaps best defined by the saying “What’s old is new again”. In what seems to be an effort to romanticise an otherwise chaotic world, older trends are resurfacing and being labelled as the “ vintage aesthetic”, which is further divided into the 90s aesthetic, the 70s aesthetic, the 00s aesthetic and so on. These trends, while appearing as if limited to fashion, music or pop culture at first, are believed by some to actually have a deeper psychological basis. Evident in TikToks by popular influencers, there seems to be a puzzling yet immense sense of nostalgia for things that most members of Gen Z never even experienced firsthand. For instance, the recent emphasis on “cottagecore” appears to reflect a yearning for cosiness, comfort and a harmonious connection with nature, reminiscent of a pastoral life (Higgins, 2024). Likewise, social media has lately seen a surge in the so-called “tradwife” movement. The term “tradwife” (short for traditional wife) refers to a group of women who embrace traditional gender roles in their marriage and devote their time to homemaking and child-rearing, often using their platform to share recipes and cleaning tips. On TikTok, videos with the hashtag “#tradwife” has been viewed over 251 million times. The trend appears to cater to a sentimental appeal among those who idealise the perceived simpler and safer nature of the 1950s lifestyle (Doyle, 2024).

“Glorifying these yesteryear ways of living has become Gen Z’s way of passively rebelling against the pressures of hustle culture and coping with the stress of the 21st century lifestyle.”

The glamorisation of the sugar baby lifestyle on TikTok also appears to be related to this. The term sugar baby refers to a younger person (typically a woman) who provides romantic companionship or sexual intimacy to a wealthy older person (typically a man) in return for gifts or financial support (Ripes, 2022). From how it is portrayed on social media, the sugar baby lifestyle seems idyllic; an abundance of gifts, vlogs of luxurious holidays, ample free time and little to no stress (Harbron, 2022). The comment section on such posts are often full of young girls asking how to sign up and discussing how they would prefer this lifestyle any day over the academic or career stress they are currently experiencing. In fact, the popularisation of the sugar baby lifestyle was shortly followed by a trend in which young girls began to create reels with the caption referring to how their obligations prompt them to consider more traditional choices, such as “When college starts to feel like I do belong in the kitchen.” which is likely an indication of the levels of stress these young students are experiencing. It seems therefore that glorifying these yesteryear ways of living has become Gen Z’s way of passively rebelling against the pressures of hustle culture and coping with the stress of the 21st century lifestyle.

On the other hand, one way in which modern media has had a positive impact on Gen Z is that it has connected Gen Z with other people’s stories, normalising discussions about mental health. Strangers on the internet, celebrities and influencers sharing their mental health struggles on public platforms may have made it easier for others around the world to talk about theirs too (Cuncic, 2023). Likewise, increased representation of therapy and mental health struggles in the media, such as in popular movies or television shows may have promoted greater acceptance (Ramachandran, 2021). Compared to previous generations, the stigma surrounding mental health is a lot lower among Gen Z, and awareness is a lot higher. Therefore, members of Gen Z are more motivated to seek professional help (Brown, 2023) This combined with increased access to mental healthcare and a rise in efficient diagnostic methods may be a contributing reason that mental health concerns seem to be more prevalent among Gen Z.

In all of these ways and more, Gen Z collectively is the paragon of transformation. While there is the cause for concern that mental health has transformed for the worse in the 21st century, there is also cause for hope in the fact that discussions surrounding mental health, access and motivation to seek therapeutic interventions as well as treatment outcomes are all beginning to transform for the better (Spector, 2020). Additionally, through leveraging social media to revive older trends and lifestyles such as cottagecore, it is possible that Gen Z play a role in transforming the fast-paced high-pressure lifestyle of the 21st century into something more primaeval; offering us the chance to slow down, ground ourselves and find peace in the present moment. In this way, the transformation of mental wellbeing can come full-circle, by turning to the past to remedy our present.

References

-

Ahmed, A. (2024, January 16). Study shows that the screen time of Gen-Z is increasing at an alarming rate and it has some negative effects. Digital Information World. https://www.digitalinformationworld.com/2024/01/study-shows-that-screen-time-of-gen-z.html#google_vignette

-

Beddington, E. (2023, February 19). Modern stress never stops. When will our nervous systems catch up with the 21st century? the Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/feb/19/modern-stress-never-stops-when-will-our-nervous-systems-catch-up-with-the-21st-century

-

Brown, C. (2023, March 10). The rise of mental health awareness among Gen-Z: What this means for brand marketing. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesbusinesscouncil/2023/03/10/the-rise-of-mental-health-awareness-among-gen-z-what-this-means-for-brand-marketing/

-

Cuncic, A. (2023, December 30). Why Gen Z is more open to talking about their mental health. Verywell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/why-gen-z-is-more-open-to-talking-about-their-mental-health-5104730#

-

Doyle, J. (2024, July 4). What is Tradwife aesthetic and why is it trending? AD Middle East. https://www.admiddleeast.com/story/what-is-tradwife-aesthetic-and-why-is-it-trending

-

Finn, A. (2021, April 2). Do you have disaster fatigue or remote work burnout? You’re not alone. Blog | NOAA’s Office of Response & Restoration Blog. https://blog.response.restoration.noaa.gov/do-you-have-disaster-fatigue-or-remote-work-burnout-youre-not-alone

-

Gallup and Walton family Foundation. (2023, June 14). 2024 Report Card: Student Perspective on U.S. Schools. https://www.gallup.com/analytics/506663/american-youth-research.aspx#ite-544721

-

Harbron, L. (2022, October 16). The romanticisation of ‘sugar baby life’ on TikTok is hiding a dangerous reality for young women. Glamour UK. https://www.glamourmagazine.co.uk/article/sugar-babies-tiktok

-

Higgins, C. J. (2024, July 2). What is the Cottagecore aesthetic? (And why we love it). The Good Trade. https://www.thegoodtrade.com/features/what-is-cottagecore/#

-

McBride, C. (2023, November 27). How modern 21st century life is now making us sick. The Ethicalist. https://theethicalist.com/modern-21st-century-life-is-now-making-us-sick/

-

Morgan, C. P. (2023, August 28). Sadness, depression, or the blues? Maybe it’s weltschmerz. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/full-catastrophe-parenting/202308/sadness-depression-or-the-blues-maybe-its-weltschmerz#

-

Ramachandran, N. (2021, September 21). Positive on-screen mental health portrayals help teens discuss issues, survey finds. Variety. https://variety.com/2021/film/global/teen-mental-health-bbfc-uk-1235069823/

-

Ripes, J. (2023, July 26). What is a sugar baby and sugar dating? Modern Intimacy. https://www.modernintimacy.com/what-is-a-sugar-baby-and-sugar-dating/

-

Spector, N. (2020, January 11). Mental health in America: How we’ve improved and where we need to do better. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/better/lifestyle/mental-health-how-we-ve-improved-where-we-need-do-ncna1108721

-

Wright, K. W. (2023, May 3). How meditation and journaling can enhance your life. Day One | Your Journal for Life. https://dayoneapp.com/blog/meditation-and-journaling/

It may come as no surprise then that Gen Z reports the poorest mental health of any generation, according to a 2024 Gallup and Walton Family Foundation report. Although every generation has faced its own challenges, navigating the 21st century lifestyle – an environment that fosters chronically high levels of stress – appears to be an entirely different endeavour. This is especially true given that our nervous systems are adapted for fight-or-flight situations in which the threat eventually passes and cortisol levels subside (Beddington, 2023). Today, however, the pressure life places on us to be engaged in some form of activity round the clock means that we are robbed of the chance to escape, rest and recharge. For one, the endless pursuit for validation and dopamine through social media is linked to addictive behaviour and feelings of low-self worth (McBride, 2023). It does not help that there is an incessant bombardment of information at any given second from an endless supply of sources; friends, family, smartphones, computers and TVs, each placing an overwhelming level of stimulation at our fingertips.

This is particularly the case with Gen Z, who spend an average of seven hours on their phones daily (Ahmed, 2024). On the one hand, this constant connection has enabled remote working, instant communication with loved ones all around the world and the opportunity to stay aware of global affairs. The downside? We are more likely to encounter unexpected and distressing information. We might pick up our phones in order to text our friends but come across news coverage about significant global events such as pandemics, wars, natural disasters, or the impact of climate change. In this way, information begins to consume us, rather than us consuming information. As a result, we experience fatigue, anxiety and impaired concentration. Twenty-three year old Harvard linguistics graduate and content creator Adam Aleksic, known on Instagram as “@etymologynerd” hypothesises that among generation Z, this has led to pessimistic attitudes towards the future which manifests itself through the incorporation of dystopian and apocalyptic language into our day to day vocabulary, including ‘bedrotting’, ‘doom scrolling’, ‘dissociating’ and ‘spiralling’, all of which convey a sense of what has come to be known as disaster fatigue: the effect of being inundated with negative news to the extent that it begins to strain one’s emotions and health (Finn, 2021). Individuals may also experience angst fueled by the sense that we no longer control our own narratives – everything is controlled by political or corporate forces and thus we can’t do anything to stop the events which are causing our disaster fatigue, despite it taking over our screens as well as our minds.

“In what seems to be an effort to romanticise an otherwise chaotic world, older trends are resurfacing.”

The stress experienced by this generation of digital natives can also be attributed to the hustle culture in which they have grown up. Influencers on social media platforms encourage viewers to get up by 5 am, journal, meditate, go to the gym, have a nutritious breakfast and spend some time doing a hobby, all before even starting their work day. While research indeed suggests these are all good practices (Wright, 2023), these videos often imply that they need to accomplish all of these things in order to be successful, contributing to feelings of inadequacy if (or when) one or more of these goals fails to be met. In a similar way, the sponsored advertisement of “must-have” products by influencers could contribute to upward social comparison and feelings of dissatisfaction among those who may be unable to afford these items, possibly stemming from the feeling of being left out. Alongside this, there is the pressure to excel not only academically or career-wise but also in terms of looking a certain way, getting enough sleep, having a social life, learning new skills, investing in stocks and starting one’s own business, all of which seem impossible to do in the same week, let alone day! The incessant grind promoted by hustle culture, combined with the prevailing weltschmerz, a German word capturing the sentiment of weariness at the state of the world (Morgan, 2023), may culminate in burnout among Gen Z, raising the question “What is the purpose of striving when faced with seemingly inevitable adversities?”

Gen Z’s craving for stability and peace in an uncertain and workaholic world is perhaps best defined by the saying “What’s old is new again”. In what seems to be an effort to romanticise an otherwise chaotic world, older trends are resurfacing and being labelled as the “ vintage aesthetic”, which is further divided into the 90s aesthetic, the 70s aesthetic, the 00s aesthetic and so on. These trends, while appearing as if limited to fashion, music or pop culture at first, are believed by some to actually have a deeper psychological basis. Evident in TikToks by popular influencers, there seems to be a puzzling yet immense sense of nostalgia for things that most members of Gen Z never even experienced firsthand. For instance, the recent emphasis on “cottagecore” appears to reflect a yearning for cosiness, comfort and a harmonious connection with nature, reminiscent of a pastoral life (Higgins, 2024). Likewise, social media has lately seen a surge in the so-called “tradwife” movement. The term “tradwife” (short for traditional wife) refers to a group of women who embrace traditional gender roles in their marriage and devote their time to homemaking and child-rearing, often using their platform to share recipes and cleaning tips. On TikTok, videos with the hashtag “#tradwife” has been viewed over 251 million times. The trend appears to cater to a sentimental appeal among those who idealise the perceived simpler and safer nature of the 1950s lifestyle (Doyle, 2024).

“Glorifying these yesteryear ways of living has become Gen Z’s way of passively rebelling against the pressures of hustle culture and coping with the stress of the 21st century lifestyle.”

The glamorisation of the sugar baby lifestyle on TikTok also appears to be related to this. The term sugar baby refers to a younger person (typically a woman) who provides romantic companionship or sexual intimacy to a wealthy older person (typically a man) in return for gifts or financial support (Ripes, 2022). From how it is portrayed on social media, the sugar baby lifestyle seems idyllic; an abundance of gifts, vlogs of luxurious holidays, ample free time and little to no stress (Harbron, 2022). The comment section on such posts are often full of young girls asking how to sign up and discussing how they would prefer this lifestyle any day over the academic or career stress they are currently experiencing. In fact, the popularisation of the sugar baby lifestyle was shortly followed by a trend in which young girls began to create reels with the caption referring to how their obligations prompt them to consider more traditional choices, such as “When college starts to feel like I do belong in the kitchen.” which is likely an indication of the levels of stress these young students are experiencing. It seems therefore that glorifying these yesteryear ways of living has become Gen Z’s way of passively rebelling against the pressures of hustle culture and coping with the stress of the 21st century lifestyle.

On the other hand, one way in which modern media has had a positive impact on Gen Z is that it has connected Gen Z with other people’s stories, normalising discussions about mental health. Strangers on the internet, celebrities and influencers sharing their mental health struggles on public platforms may have made it easier for others around the world to talk about theirs too (Cuncic, 2023). Likewise, increased representation of therapy and mental health struggles in the media, such as in popular movies or television shows may have promoted greater acceptance (Ramachandran, 2021). Compared to previous generations, the stigma surrounding mental health is a lot lower among Gen Z, and awareness is a lot higher. Therefore, members of Gen Z are more motivated to seek professional help (Brown, 2023) This combined with increased access to mental healthcare and a rise in efficient diagnostic methods may be a contributing reason that mental health concerns seem to be more prevalent among Gen Z.

In all of these ways and more, Gen Z collectively is the paragon of transformation. While there is the cause for concern that mental health has transformed for the worse in the 21st century, there is also cause for hope in the fact that discussions surrounding mental health, access and motivation to seek therapeutic interventions as well as treatment outcomes are all beginning to transform for the better (Spector, 2020). Additionally, through leveraging social media to revive older trends and lifestyles such as cottagecore, it is possible that Gen Z play a role in transforming the fast-paced high-pressure lifestyle of the 21st century into something more primaeval; offering us the chance to slow down, ground ourselves and find peace in the present moment. In this way, the transformation of mental wellbeing can come full-circle, by turning to the past to remedy our present.

References

-

Ahmed, A. (2024, January 16). Study shows that the screen time of Gen-Z is increasing at an alarming rate and it has some negative effects. Digital Information World. https://www.digitalinformationworld.com/2024/01/study-shows-that-screen-time-of-gen-z.html#google_vignette

-

Beddington, E. (2023, February 19). Modern stress never stops. When will our nervous systems catch up with the 21st century? the Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/feb/19/modern-stress-never-stops-when-will-our-nervous-systems-catch-up-with-the-21st-century

-

Brown, C. (2023, March 10). The rise of mental health awareness among Gen-Z: What this means for brand marketing. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesbusinesscouncil/2023/03/10/the-rise-of-mental-health-awareness-among-gen-z-what-this-means-for-brand-marketing/

-

Cuncic, A. (2023, December 30). Why Gen Z is more open to talking about their mental health. Verywell Mind. https://www.verywellmind.com/why-gen-z-is-more-open-to-talking-about-their-mental-health-5104730#

-

Doyle, J. (2024, July 4). What is Tradwife aesthetic and why is it trending? AD Middle East. https://www.admiddleeast.com/story/what-is-tradwife-aesthetic-and-why-is-it-trending

-

Finn, A. (2021, April 2). Do you have disaster fatigue or remote work burnout? You’re not alone. Blog | NOAA’s Office of Response & Restoration Blog. https://blog.response.restoration.noaa.gov/do-you-have-disaster-fatigue-or-remote-work-burnout-youre-not-alone

-

Gallup and Walton family Foundation. (2023, June 14). 2024 Report Card: Student Perspective on U.S. Schools. https://www.gallup.com/analytics/506663/american-youth-research.aspx#ite-544721

-

Harbron, L. (2022, October 16). The romanticisation of ‘sugar baby life’ on TikTok is hiding a dangerous reality for young women. Glamour UK. https://www.glamourmagazine.co.uk/article/sugar-babies-tiktok

-

Higgins, C. J. (2024, July 2). What is the Cottagecore aesthetic? (And why we love it). The Good Trade. https://www.thegoodtrade.com/features/what-is-cottagecore/#

-

McBride, C. (2023, November 27). How modern 21st century life is now making us sick. The Ethicalist. https://theethicalist.com/modern-21st-century-life-is-now-making-us-sick/

-

Morgan, C. P. (2023, August 28). Sadness, depression, or the blues? Maybe it’s weltschmerz. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/full-catastrophe-parenting/202308/sadness-depression-or-the-blues-maybe-its-weltschmerz#

-

Ramachandran, N. (2021, September 21). Positive on-screen mental health portrayals help teens discuss issues, survey finds. Variety. https://variety.com/2021/film/global/teen-mental-health-bbfc-uk-1235069823/

-

Ripes, J. (2023, July 26). What is a sugar baby and sugar dating? Modern Intimacy. https://www.modernintimacy.com/what-is-a-sugar-baby-and-sugar-dating/

-

Spector, N. (2020, January 11). Mental health in America: How we’ve improved and where we need to do better. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/better/lifestyle/mental-health-how-we-ve-improved-where-we-need-do-ncna1108721

-

Wright, K. W. (2023, May 3). How meditation and journaling can enhance your life. Day One | Your Journal for Life. https://dayoneapp.com/blog/meditation-and-journaling/