Searching for truth and justice in politics and history is an excruciatingly frustrating endeavour, as can be experienced at a current FOAM exhibition. The visitor is confronted with the darkest chapter of Spain’s recent history and how it affected the collective memory of generations, all while being nudged into questioning narrative and truth.

When thinking about truth, one might conceptualise it as a rational, definite entity. The truth can be uncovered, scientists present evidence for it, and eventually the truths of the world will find their way into common knowledge. We will adopt that knowledge, maybe even let ourselves be guided by it, and trust the underlying essence of it. But what if the truth was irrational, malleable, elusive?

“Theatre of Broken Memories” exhibits the work of Dutch photographer Bebe Blanco Agterberg, and demonstrates how truth and tale, fact and fiction are inextricably linked in the making of history and politics. The artist directs her camera, and with it the attention of the visitor, to Spain’s decades under dictatorship, specifically focussing on the aftermath and how the country has dealt with its violent past.

© Bebe Blanco Agterberg, 2020

The Spanish general Francisco Franco gained power as the military leader of the Nationalist forces during the Civil War that lasted from 1936 to 1939. After the last Republican forces in Valencia surrendered, Franco established a regime of oppression, terror, and almost unrestricted power for himself. Especially in the first years of his power, but also in the following decades, hundreds of thousands of people died – in the war, in state executions of political opponents, through persecution of minorities and vulnerable members of society (1, 3). Also, an estimated 300,000 babies were abducted and trafficked during Franco’s dictatorship (2, 3). Often, they were taken from families which were deemed unworthy, for political or social reasons, and put in families who were known to support the Nationalist forces and the regime. Stealing the Republican offspring was hoped to slowly eradicate dissenting families and with them their thoughts, hopes, memories, and worldview. Traditions such as flamenco and bullfighting were encouraged in the creation of a united Spanish identity, while cultural or linguistic deviations from the regime’s vision were censored, suppressed, punished (4, 5).

The atrocities committed by and through the regime are deeply ingrained in Spanish history and society, yet remain unmentioned, silenced, and forgotten. After Franco’s death in 1975, the state successfully transitioned to a democracy within a few years, but at a high cost: The total distortion of Spain’s collective memory. The so-called “Pact of Forgetting” (Pacto del Olvido) and the “Amnesty Law” (Ley de Amnistía) passed in 1977 might have allowed the country to move on from the past decades of suppression and violence, but it also ensured that the crimes of the Civil War and Franco’s regime would not be investigated nor penalised (1).

Today, the abducted babies are grown-ups, even grandparents; their biological parents might have died long ago and cannot search for them anymore. Thousands of unidentified bodies remain in mass graves all over Spain. The fallen of the Civil War, the political prisoners and the regime’s victims are nameless and faceless, stripped of the opportunity to tell their stories and experience reparations or justice. Only very recently have efforts to deal with the past increased. Franco’s remains were exhumed and his enormous memorial was removed from the Valley of the Fallen, a burial site intended for the victims of the Civil War, a few years ago – more than 40 years after his death. These efforts and legal battles culminated in a new approach consolidated by laws that were passed as recently as October 2022, promising justice and reparations, for example through a DNA bank that could help with identifying victims (1).

Photo from Aki’s visit, 14 January 2023, FOAM Fotografiemuseum, Amsterdam

The exhibition at FOAM is one more steppingstone on the long path of recovering an entire country’s memory. Bebe Blanco Agterberg might have been inspired by her personal and familiar history, but she really speaks for a generation that seeks the truth, regardless of how uncomfortable or bloody it might be. She invites the visitor to accompany her on this deeply emotional and quite distressing journey of uncovering Spain’s dark chapter.

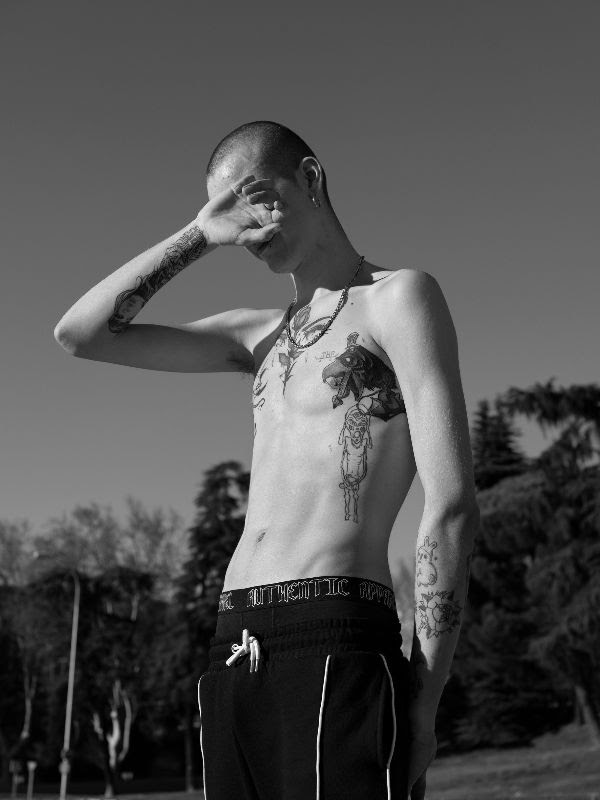

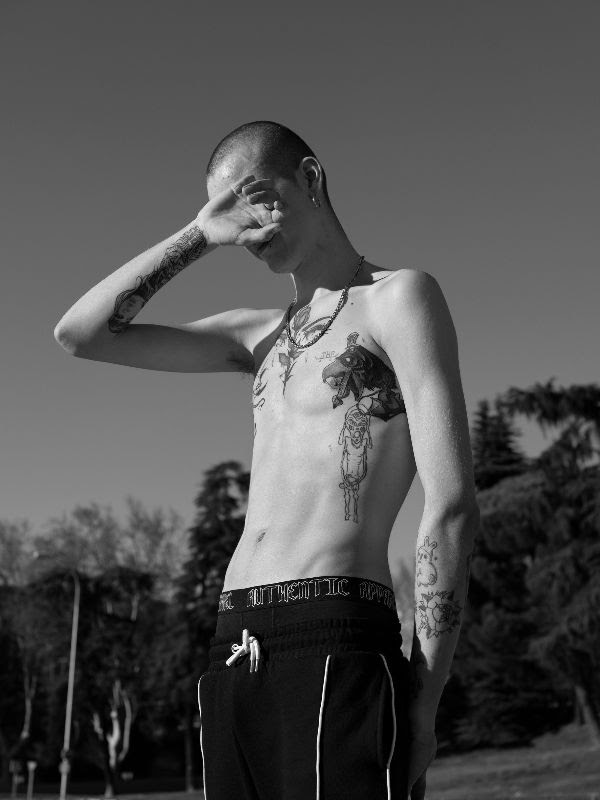

Entering a dark room and thinking about Franco’s regime is certainly an intimidating setting for an exhibition, yet it is the artist’s clear and calm recorded voice that first sounds inviting but then truly pierces marrow and bone. In the centre of the room, a triangular display of black and white photographs attracts the visitor to join endless rounds and rounds around the installation. One side of the triangular setup is lit up and the narrator illustrates the situation or person in the photos, one by one, six in a row. There is a young man with tattoos skating in front of a memorial in Madrid. A shadow of a man walking on the street. A wall with patches of paint over something that looks like bullet holes. The seemingly ordinary moments captured on camera gain depth and meaning as they are put into context by the narrator’s enriching details.

The light switches, and the visitors in the room walk around the installation to find the same set of photos, again illuminated, yet in a different order. Attentive listeners will then notice the first changes to the illustrative narrations. The light switches again, and the visitors follow around to find again the same photos with again slightly different stories accompanying them. The skater in front of the memorial knows not much about Franco, only that he once was the leader of Spain. The skater in front of the memorial has heard a lot about the great Franco and how he helped Spain’s economy grow. The skater in front of the memorial has heard about Franco, what a cruel man he was and what atrocious things he has done.

With every light switch, every moment of hesitation by the narrator before restarting the photo’s stories, every new version of the same captured moment, the underlying truth obscures a little further. It is confusing and unsettling, this search for the real, true version and yet never knowing which one it might be. Not enough information to determine which story to believe, yet too much information to ignore the consequences of each one. This overwhelming lack of objectivity, of facts and reliable sources sends a shiver down the spine and makes you wonder: How can we know which story is the truth? Do we not deserve to know? Do we not deserve to trust the artist’s narration of her photographed subjects and go home in peace?

You might not go home in peace but lost in thought. Maybe appreciative of the freedom of information and narrative that we have at hand now. Maybe hoping that the families will find answers and truth in their ceaseless search for the killed, silenced, abducted, and stolen. Maybe questioning if we can ever know truth, or if there even is such a thing as objective truth. <<

The exhibition Theatre of Broken Memories | Bebe Blanco Agterberg is on display until 5th of March, 2023 at FOAM Fotografiemuseum, Amsterdam.

References

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/can-a-new-law-help-spain-move-on-from-its-fascist-past

- https://time.com/5321938/spain-stolen-babies-franco-trial/

- https://jacobin.com/2020/10/historical-memory-law-franco-spain-victims

- https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/francisco-franco#section_4

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/complicated-history-flamenco-spain-180973398/

Searching for truth and justice in politics and history is an excruciatingly frustrating endeavour, as can be experienced at a current FOAM exhibition. The visitor is confronted with the darkest chapter of Spain’s recent history and how it affected the collective memory of generations, all while being nudged into questioning narrative and truth.

When thinking about truth, one might conceptualise it as a rational, definite entity. The truth can be uncovered, scientists present evidence for it, and eventually the truths of the world will find their way into common knowledge. We will adopt that knowledge, maybe even let ourselves be guided by it, and trust the underlying essence of it. But what if the truth was irrational, malleable, elusive?

“Theatre of Broken Memories” exhibits the work of Dutch photographer Bebe Blanco Agterberg, and demonstrates how truth and tale, fact and fiction are inextricably linked in the making of history and politics. The artist directs her camera, and with it the attention of the visitor, to Spain’s decades under dictatorship, specifically focussing on the aftermath and how the country has dealt with its violent past.

© Bebe Blanco Agterberg, 2020

The Spanish general Francisco Franco gained power as the military leader of the Nationalist forces during the Civil War that lasted from 1936 to 1939. After the last Republican forces in Valencia surrendered, Franco established a regime of oppression, terror, and almost unrestricted power for himself. Especially in the first years of his power, but also in the following decades, hundreds of thousands of people died – in the war, in state executions of political opponents, through persecution of minorities and vulnerable members of society11, 3. Also, an estimated 300,000 babies were abducted and trafficked during Franco’s dictatorship22, 3. Often, they were taken from families which were deemed unworthy, for political or social reasons, and put in families who were known to support the Nationalist forces and the regime. Stealing the Republican offspring was hoped to slowly eradicate dissenting families and with them their thoughts, hopes, memories, and worldview. Traditions such as flamenco and bullfighting were encouraged in the creation of a united Spanish identity, while cultural or linguistic deviations from the regime’s vision were censored, suppressed, punished34, 5.

The atrocities committed by and through the regime are deeply ingrained in Spanish history and society, yet remain unmentioned, silenced, and forgotten. After Franco’s death in 1975, the state successfully transitioned to a democracy within a few years, but at a high cost: The total distortion of Spain’s collective memory. The so-called “Pact of Forgetting” (Pacto del Olvido) and the “Amnesty Law” (Ley de Amnistía) passed in 1977 might have allowed the country to move on from the past decades of suppression and violence, but it also ensured that the crimes of the Civil War and Franco’s regime would not be investigated nor penalised41.

Today, the abducted babies are grown-ups, even grandparents; their biological parents might have died long ago and cannot search for them anymore. Thousands of unidentified bodies remain in mass graves all over Spain. The fallen of the Civil War, the political prisoners and the regime’s victims are nameless and faceless, stripped of the opportunity to tell their stories and experience reparations or justice. Only very recently have efforts to deal with the past increased. Franco’s remains were exhumed and his enormous memorial was removed from the Valley of the Fallen, a burial site intended for the victims of the Civil War, a few years ago – more than 40 years after his death. These efforts and legal battles culminated in a new approach consolidated by laws that were passed as recently as October 2022, promising justice and reparations, for example through a DNA bank that could help with identifying victims51.

Photo from Aki’s visit, 14 January 2023, FOAM Fotografiemuseum, Amsterdam

The exhibition at FOAM is one more steppingstone on the long path of recovering an entire country’s memory. Bebe Blanco Agterberg might have been inspired by her personal and familiar history, but she really speaks for a generation that seeks the truth, regardless of how uncomfortable or bloody it might be. She invites the visitor to accompany her on this deeply emotional and quite distressing journey of uncovering Spain’s dark chapter.

Entering a dark room and thinking about Franco’s regime is certainly an intimidating setting for an exhibition, yet it is the artist’s clear and calm recorded voice that first sounds inviting but then truly pierces marrow and bone. In the centre of the room, a triangular display of black and white photographs attracts the visitor to join endless rounds and rounds around the installation. One side of the triangular setup is lit up and the narrator illustrates the situation or person in the photos, one by one, six in a row. There is a young man with tattoos skating in front of a memorial in Madrid. A shadow of a man walking on the street. A wall with patches of paint over something that looks like bullet holes. The seemingly ordinary moments captured on camera gain depth and meaning as they are put into context by the narrator’s enriching details.

The light switches, and the visitors in the room walk around the installation to find the same set of photos, again illuminated, yet in a different order. Attentive listeners will then notice the first changes to the illustrative narrations. The light switches again, and the visitors follow around to find again the same photos with again slightly different stories accompanying them. The skater in front of the memorial knows not much about Franco, only that he once was the leader of Spain. The skater in front of the memorial has heard a lot about the great Franco and how he helped Spain’s economy grow. The skater in front of the memorial has heard about Franco, what a cruel man he was and what atrocious things he has done.

With every light switch, every moment of hesitation by the narrator before restarting the photo’s stories, every new version of the same captured moment, the underlying truth obscures a little further. It is confusing and unsettling, this search for the real, true version and yet never knowing which one it might be. Not enough information to determine which story to believe, yet too much information to ignore the consequences of each one. This overwhelming lack of objectivity, of facts and reliable sources sends a shiver down the spine and makes you wonder: How can we know which story is the truth? Do we not deserve to know? Do we not deserve to trust the artist’s narration of her photographed subjects and go home in peace?

You might not go home in peace but lost in thought. Maybe appreciative of the freedom of information and narrative that we have at hand now. Maybe hoping that the families will find answers and truth in their ceaseless search for the killed, silenced, abducted, and stolen. Maybe questioning if we can ever know truth, or if there even is such a thing as objective truth. <<

The exhibition Theatre of Broken Memories | Bebe Blanco Agterberg is on display until 5th of March, 2023 at FOAM Fotografiemuseum, Amsterdam.

References

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/can-a-new-law-help-spain-move-on-from-its-fascist-past

- https://time.com/5321938/spain-stolen-babies-franco-trial/

- https://jacobin.com/2020/10/historical-memory-law-franco-spain-victims

- https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/francisco-franco#section_4

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/complicated-history-flamenco-spain-180973398/