When discussions turn into “either/or”-debates, when arguments are oversimplified into dichotomies and when “being in favour” of something equals “being against” another thing – should we not take a step back and think of ways to find harmony in what appears disharmonious? This article argues that in debates like idealism versus materialism, there is benefit and flaw to both viewpoints. Both Buddhism and science encourage us to consider matters holistically.

When discussions turn into “either/or”-debates, when arguments are oversimplified into dichotomies and when “being in favour” of something equals “being against” another thing – should we not take a step back and think of ways to find harmony in what appears disharmonious? This article argues that in debates like idealism versus materialism, there is benefit and flaw to both viewpoints. Both Buddhism and science encourage us to consider matters holistically.

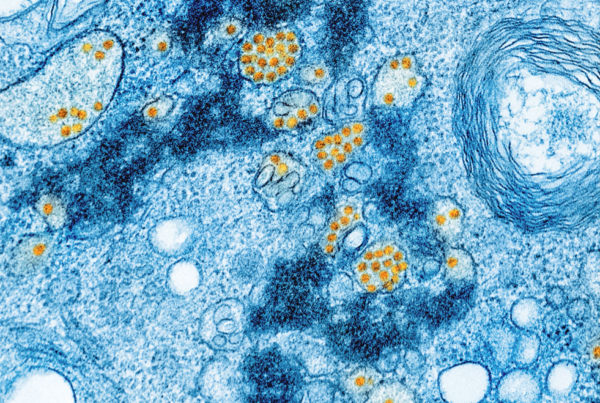

Photo by Lahiru Supunchandra

Photo by Lahiru Supunchandra

Cats or dogs? Chocolate or vanilla? Summer or winter? Chances are, you take a passionate stance for one of these. Brimming with energy, you are ready to shoot down every opposing argument, trying to prove that your side of the dichotomy is the right one. Many dichotomic debates are trivial and easily settled with an agreement to disagree. However, we humans also turned more profound issues into dichotomic debates, influencing our thoughts and behaviours. For example, contradicting worldviews are reflected in the nature-versus-nurture debate, “right-winged” versus “left-winged” political decision-making, or the idealism versus materialism discussion. It is no surprise that “either/or”- debates can turn into conflicts when viewpoints appear fundamentally incompatible. In turn, when such conflicts accumulate on a broadscale level, like national or international politics, we sometimes observe such situations to escalate into wars.

One such war is the Vietnam War (1955 – 1975), which cost thousands of human lives. Many war-survivors went on to tell their story of suffering – yet a certain survivor painted his story in the colours of hope. The late Buddhist monk Thich Nath Hanh (1926 – 2022) lived on to teach the lessons of war, starting by founding the Order of Interbeing in Plum Village. Central to his Buddhistic studies and teachings was the nature of human suffering, how to come to terms with oneself and those who caused one’s suffering. According to Nath Hanh, a crucial step in finding peace is internalising the concept of “interbeing” – the belief that every human and object ultimately depend on one another (Plum Village App, 2020). To make this concept more graspable, he often utilised a sheet of paper as an analogy: While dichotomic viewpoints oppose each other like the left and right side of a sheet of paper, it is also the case that “we cannot take out the left out of the right and the right out of the left. […]. The left has to inter-be with the right – the left is not the enemy of the right. The left has to lean on the right in order to manifest itself” (Plum Village App, 2020).

Nath Hanh contrasts interbeing with a “mind of discrimination” that seeks disparity and opposition – a practice that supposedly limits our ability to understand our emotions, our loved ones and ultimately the world. As an example of discriminatory thinking, Nath Hanh introduces the question of whether the mind is produced by matter or if the mind produces matter, which is essentially the materialism versus idealism debate previously mentioned. He applies the concept of interbeing to this debate, stating that we need to acknowledge how both propositions hold some truth and some flaws that complement each other.

“We cannot take out the left out of the right and the right out of the left. The left has to inter-be with the right – the left is not the enemy of the right.”

Spirituality aside – how can one know if it is not better to side with one party and avoid ambiguity? After all, the materialistic stance claims that all objects consist of concrete and graspable matter (Ramsey, 2022), essentially laying the foundation for physics and medicine. To give one example, consider the discipline of neuroscience: Humans were and are interested in studying the brain to understand cognitive impairment, but today’s fundamental research has revealed much more about the neurological mechanisms underlying cognition, emotion and perception (Purves et al., 2012). We now not only know that mental images can be traced back to electrical and chemical activity between neurons, but by measuring that activity, we can even deduce what type of mental image was present. This is possible only to a limited extent (such as differentiating whether a person sees a house or a face), yet it proves that thought is ultimately a reflection of physically measurable neuronal interactions (Purves et al., 2012). It is hard to argue that there is any reason to derogate the materialistic advances that paved the way for science, also because they freed us from faulty beliefs such as “we must offer a human sacrifice to please the Thunder God!”.

What started out as scientific foresight has, however, morphed into a modern form of materialism that entails rather negative connotations. Generally speaking, this modern definition (discussed later) speaks of materialism as a value-system applied to lifestyle-choices beyond the realm of scientific investigation. An “ancient” materialist can therefore be distinguished from a “modern” materialist by the domains they apply their materialistic worldview onto – yet both viewpoints are based on the key notion that anything objective and physical is superior to anything abstract and mental. As defined by professor of psychology Tim Kasser, nowadays being materialistic means “to have values that put a relatively high priority on making a lot of money and having many possessions” (American Psychological Association, 2016). It is a common stereotype that materialists aim to acquire a multitude of physical belongings while disregarding more abstract concepts like open-mindedness, honesty, spirituality and generally anything that does not have a heavy price-tag attached to it. Although only a hypothetical explanation, Kasser suggests that a materialistic value-orientation is insufficient in satisfying our psychological cravings for social connectedness and feelings of competence. He also states that, in his research focused on materialism and wellbeing, the former is consistently linked to symptoms of physical and mental ill-health like headaches and depression (American Psychological Association, 2016). In short, the materialist viewpoints that allowed scientific progress now take a toll on our health.

It appears that materialism does not offer all the answers to life. Presumably, it lacks consideration of something crucial to the human condition: The mind, with all its abstract, subjective and ungraspable elements. One philosophical line of thought concerned with the subjectiveness of our experience is idealism, which claims that reality is nothing more than a product of our minds. One particular line of idealism dominated 19th-century philosophy, pioneered by G. W. F. Hegel. He claimed that “the finite world is a reflection of mind” (Encyclopedia Britannica, 2018) and that truth is based on the internal coherence of thoughts, not how well thoughts capture objective reality.

“It becomes evident that science does not support the notion that one side of the materialism versus idealism-debate is favourable over the other.”

What appears to be bold statements is in fact backed up by neuroscientific research. Our perception of the world seems to be less tied to objective reality than one would expect (Purves et al., 2012). Taking visual perception as an example, science is unable to explain the exact mechanisms by which we figure out how bright objects are or where they are located in the three-dimensional space. Based on the raw stimuli we get (such as illumination-values, reflectance or the two-dimensional image on our retina), it is impossible to navigate our world. It follows that the brain plays a huge role in constructing and editing our sensory input to allow effective interaction with our surroundings. Our mind might aim at representing the external world, but few of those mental representations are purely rooted in objectively measurable stimuli – leading to the thought that idealism is not all too wrong in stating that our reality is more subjective than materialists would like to admit.

In considering these (neuro)psychological findings, it becomes evident that science does not support the notion that one side of the materialism versus idealism-debate is favourable over the other. An extreme focus on the materialistic world (and possessions) is related to negative health-outcomes – yet we would be missing out on science and technology if early materialistic minds had not argued that abstract and supernatural beliefs were counterproductive to evolving civilization. On the other hand, idealism claims that there is no objective reality, which appears appalling when considering how graspable and real the external world appears to us – yet, neuroscientific research proves us wrong by demonstrating how our experiences are not ascribable to the objectively measurable traits of the material world alone.

In the end, adopting the spiritual perspective and accepting both sides of a debate as interdependent appears worth the price of ambiguous answers. Settling within the comfort of a one-sided discussion may cause us to miss out on important insights, so maybe our efforts should not be directed at proving points, but at seeking harmony between the truths found on both sides of a dichotomous argument. It turns out that both Buddhism and science harmoniously unite in encouraging us to investigate how contradicting views compliment each other and to honour both their strengths and weaknesses.After all, nobody said you can’t enjoy both a ball of chocolate and vanilla ice cream. <<

References

– American Psychological Association. (2014, December 16). What psychology says about materialism and the holidays [Press release]. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2014/12/materialism-holidays

– Encyclopaedia Britannica (2018, October 30). Absolute idealism. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Absolute-Idealism

– Purves, D., Cabeza, R., Huettel, S. A., LaBar, K. S., Platt, M. L., Woldorff, M. G. (2012). Principles of Cognitive Neuroscience. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associated, Inc. Publishers

– Plum Village App. (2020, June 1). Non-duality: No mud, no lotus. Thich Nath Hanh (short teaching video) [Video]. Youtube. https://youtu.be/schlgVvKoDk

– Plum Village. The order of interbeing (n.d.) Plum Village. https://plumvillage.org/de/order-of-interbeing/

– Ramsey, W. (2022, Spring) Eliminative Materialism, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2022/entries/materialism-eliminative/

Cats or dogs? Chocolate or vanilla? Summer or winter? Chances are, you take a passionate stance for one of these. Brimming with energy, you are ready to shoot down every opposing argument, trying to prove that your side of the dichotomy is the right one. Many dichotomic debates are trivial and easily settled with an agreement to disagree. However, we humans also turned more profound issues into dichotomic debates, influencing our thoughts and behaviours. For example, contradicting worldviews are reflected in the nature-versus-nurture debate, “right-winged” versus “left-winged” political decision-making, or the idealism versus materialism discussion. It is no surprise that “either/or”- debates can turn into conflicts when viewpoints appear fundamentally incompatible. In turn, when such conflicts accumulate on a broadscale level, like national or international politics, we sometimes observe such situations to escalate into wars.

One such war is the Vietnam War (1955 – 1975), which cost thousands of human lives. Many war-survivors went on to tell their story of suffering – yet a certain survivor painted his story in the colours of hope. The late Buddhist monk Thich Nath Hanh (1926 – 2022) lived on to teach the lessons of war, starting by founding the Order of Interbeing in Plum Village. Central to his Buddhistic studies and teachings was the nature of human suffering, how to come to terms with oneself and those who caused one’s suffering. According to Nath Hanh, a crucial step in finding peace is internalising the concept of “interbeing” – the belief that every human and object ultimately depend on one another (Plum Village App, 2020). To make this concept more graspable, he often utilised a sheet of paper as an analogy: While dichotomic viewpoints oppose each other like the left and right side of a sheet of paper, it is also the case that “we cannot take out the left out of the right and the right out of the left. […]. The left has to inter-be with the right – the left is not the enemy of the right. The left has to lean on the right in order to manifest itself” (Plum Village App, 2020).

Nath Hanh contrasts interbeing with a “mind of discrimination” that seeks disparity and opposition – a practice that supposedly limits our ability to understand our emotions, our loved ones and ultimately the world. As an example of discriminatory thinking, Nath Hanh introduces the question of whether the mind is produced by matter or if the mind produces matter, which is essentially the materialism versus idealism debate previously mentioned. He applies the concept of interbeing to this debate, stating that we need to acknowledge how both propositions hold some truth and some flaws that complement each other.

“We cannot take out the left out of the right and the right out of the left. The left has to inter-be with the right – the left is not the enemy of the right.”

Spirituality aside – how can one know if it is not better to side with one party and avoid ambiguity? After all, the materialistic stance claims that all objects consist of concrete and graspable matter (Ramsey, 2022), essentially laying the foundation for physics and medicine. To give one example, consider the discipline of neuroscience: Humans were and are interested in studying the brain to understand cognitive impairment, but today’s fundamental research has revealed much more about the neurological mechanisms underlying cognition, emotion and perception (Purves et al., 2012). We now not only know that mental images can be traced back to electrical and chemical activity between neurons, but by measuring that activity, we can even deduce what type of mental image was present. This is possible only to a limited extent (such as differentiating whether a person sees a house or a face), yet it proves that thought is ultimately a reflection of physically measurable neuronal interactions (Purves et al., 2012). It is hard to argue that there is any reason to derogate the materialistic advances that paved the way for science, also because they freed us from faulty beliefs such as “we must offer a human sacrifice to please the Thunder God!”.

What started out as scientific foresight has, however, morphed into a modern form of materialism that entails rather negative connotations. Generally speaking, this modern definition (discussed later) speaks of materialism as a value-system applied to lifestyle-choices beyond the realm of scientific investigation. An “ancient” materialist can therefore be distinguished from a “modern” materialist by the domains they apply their materialistic worldview onto – yet both viewpoints are based on the key notion that anything objective and physical is superior to anything abstract and mental. As defined by professor of psychology Tim Kasser, nowadays being materialistic means “to have values that put a relatively high priority on making a lot of money and having many possessions” (American Psychological Association, 2016). It is a common stereotype that materialists aim to acquire a multitude of physical belongings while disregarding more abstract concepts like open-mindedness, honesty, spirituality and generally anything that does not have a heavy price-tag attached to it. Although only a hypothetical explanation, Kasser suggests that a materialistic value-orientation is insufficient in satisfying our psychological cravings for social connectedness and feelings of competence. He also states that, in his research focused on materialism and wellbeing, the former is consistently linked to symptoms of physical and mental ill-health like headaches and depression (American Psychological Association, 2016). In short, the materialist viewpoints that allowed scientific progress now take a toll on our health.

It appears that materialism does not offer all the answers to life. Presumably, it lacks consideration of something crucial to the human condition: The mind, with all its abstract, subjective and ungraspable elements. One philosophical line of thought concerned with the subjectiveness of our experience is idealism, which claims that reality is nothing more than a product of our minds. One particular line of idealism dominated 19th-century philosophy, pioneered by G. W. F. Hegel. He claimed that “the finite world is a reflection of mind” (Encyclopedia Britannica, 2018) and that truth is based on the internal coherence of thoughts, not how well thoughts capture objective reality.

“It becomes evident that science does not support the notion that one side of the materialism versus idealism-debate is favourable over the other.”

What appears to be bold statements is in fact backed up by neuroscientific research. Our perception of the world seems to be less tied to objective reality than one would expect (Purves et al., 2012). Taking visual perception as an example, science is unable to explain the exact mechanisms by which we figure out how bright objects are or where they are located in the three-dimensional space. Based on the raw stimuli we get (such as illumination-values, reflectance or the two-dimensional image on our retina), it is impossible to navigate our world. It follows that the brain plays a huge role in constructing and editing our sensory input to allow effective interaction with our surroundings. Our mind might aim at representing the external world, but few of those mental representations are purely rooted in objectively measurable stimuli – leading to the thought that idealism is not all too wrong in stating that our reality is more subjective than materialists would like to admit.

In considering these (neuro)psychological findings, it becomes evident that science does not support the notion that one side of the materialism versus idealism-debate is favourable over the other. An extreme focus on the materialistic world (and possessions) is related to negative health-outcomes – yet we would be missing out on science and technology if early materialistic minds had not argued that abstract and supernatural beliefs were counterproductive to evolving civilization. On the other hand, idealism claims that there is no objective reality, which appears appalling when considering how graspable and real the external world appears to us – yet, neuroscientific research proves us wrong by demonstrating how our experiences are not ascribable to the objectively measurable traits of the material world alone.

In the end, adopting the spiritual perspective and accepting both sides of a debate as interdependent appears worth the price of ambiguous answers. Settling within the comfort of a one-sided discussion may cause us to miss out on important insights, so maybe our efforts should not be directed at proving points, but at seeking harmony between the truths found on both sides of a dichotomous argument. It turns out that both Buddhism and science harmoniously unite in encouraging us to investigate how contradicting views compliment each other and to honour both their strengths and weaknesses.After all, nobody said you can’t enjoy both a ball of chocolate and vanilla ice cream. <<