The aftermath of receiving a mental health diagnosis can feel like the world as you know it has fundamentally changed. There is now a permanent label attached to you, that will always be part of a chapter in your story that is now beginning, a chapter marked by the journey towards feeling okay again. Conversations with friends have now become marked by your emotions permanently appearing to be lost in translation. A tangible disconnect has been created between you and those who are supposed to be closest to you, an inevitable storm looming on the horizon. You feel like no one truly understands you and before you know it loneliness has become a silent companion in every mental battle you face.

The aftermath of receiving a mental health diagnosis can feel like the world as you know it has fundamentally changed. There is now a permanent label attached to you, that will always be part of a chapter in your story that is now beginning, a chapter marked by the journey towards feeling okay again. Conversations with friends have now become marked by your emotions permanently appearing to be lost in translation. A tangible disconnect has been created between you and those who are supposed to be closest to you, an inevitable storm looming on the horizon. You feel like no one truly understands you and before you know it loneliness has become a silent companion in every mental battle you face.

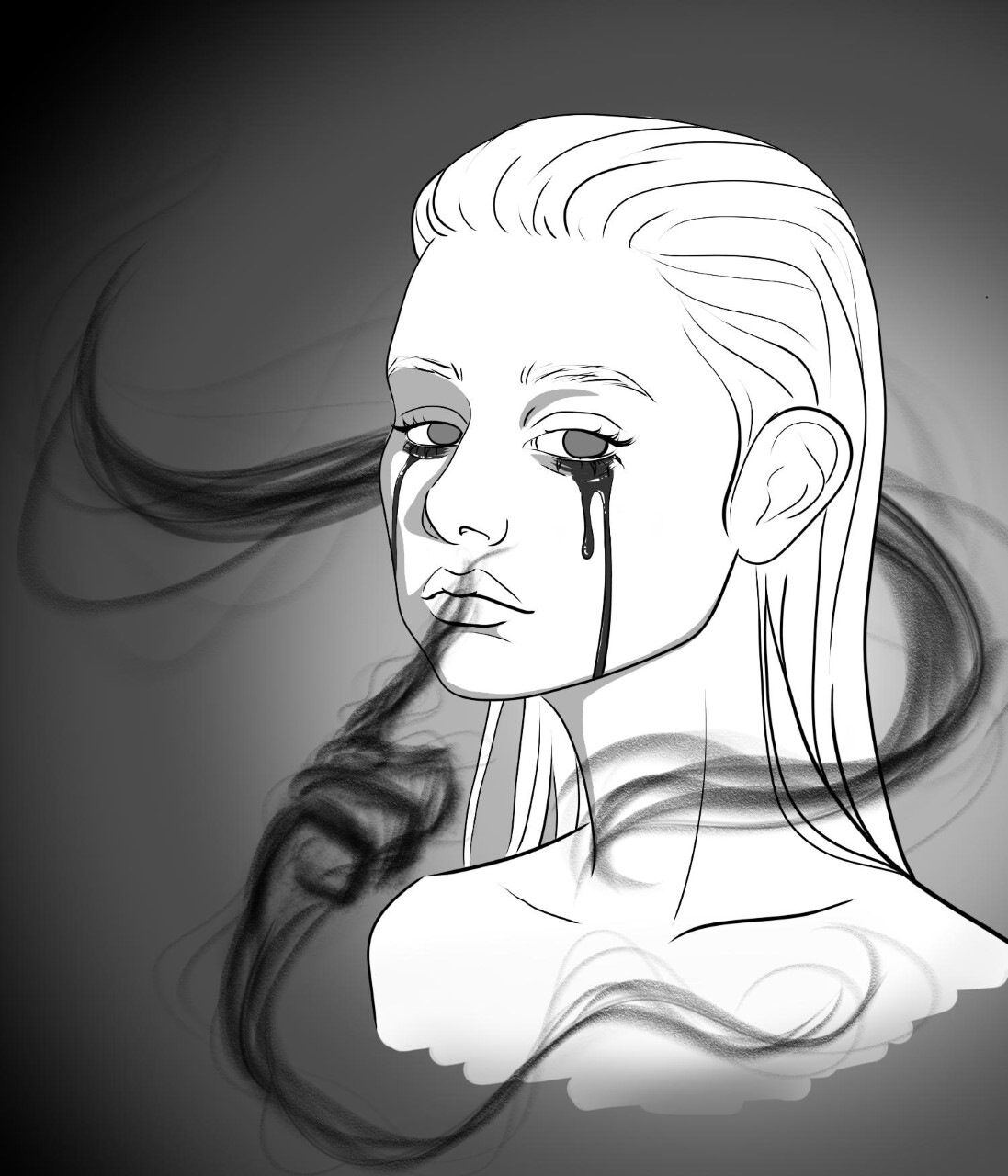

Illustration by Nina Kollof

Illustration by Nina Kollof

Several lines of research investigate the feeling of an intense disconnection from other people after receiving a mental health diagnosis. A study showed that loneliness was associated with six common mental disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, depression, OCD, phobia, panic disorder, mixed anxiety and depressive disorder), with the strongest link to depression (Meltzer et al., 2012). A qualitative meta-synthesis investigating loneliness in personality disorders found several important themes (Ikhtabi et al., 2022); namely disconnection and emptiness: a haunting alienation, alienation arising from childhood experiences; but also extended to existential and societal themes, such as recovery, embedded in a social world and experiences of existential loneliness. These themes highlight the multifaceted nature of loneliness, reflecting a complex interconnection between personal and societal factors. While we’ve all encountered loneliness at some stage, why is it significant to examine this phenomenon specifically within individuals diagnosed with mental health disorders?

Loneliness exerts a substantial toll on personal and societal health. It is a risk factor with consequences ranging from compromising physical health to increased suicide rates (Shiovitz-Ezra & Ayalon, 2010). Considering mental health problems, lower perceived social support is linked to increased symptom severity, diminished recovery, and poorer functional outcomes in those diagnosed with depression (Wang et al., 2018). The same article indicates that loneliness correlates with more pronounced anxiety and depressive symptoms. Greater loneliness of mental health service users is also directly linked to decreased rates of self-reported recovery (Ma et al., 2021). It is therefore not unreasonable to assume that loneliness aggravates the symptoms experienced across a wide range of disorders in general. As a silent adversary, the detrimental consequences of loneliness within this context emphasize the pressing need for suitable interventions and initiatives.

“As a silent adversary, the detrimental consequences of loneliness within this context emphasize the pressing need for suitable interventions and initiatives. ”

What exactly does it mean to be and feel lonely? Considering some personal accounts, the experience of loneliness fundamentally varies between individuals (Loneliness and Mental Health – Psych Matters, 2023). On a podcast episode of Psych Matters, Cat Drew, who has suffered from mental health problems and possible symptoms of psychosis since childhood, shares her personal account of what loneliness means to her. She describes it as a mismatch between how she experiences the world and how the world actually is. This contrasts the traditional perception of loneliness, that being lonely means being or feeling alone and socially isolated. Drew explains her illness allowed her ‘to always have someone to talk to, sometimes [they would] talk back, sometimes [they wouldn’t]’. Despite this, she always felt fundamentally disconnected from those around her.

Another perspective is shared by Paul Milne (Psych Matters, 2023), who was diagnosed with PTSD. For him, the experience of loneliness feels like you have lost your identity. Milne pointed out that though you may not physically be isolated, you feel alone. This is because your friends and family do not understand what is happening to you but worse than that, you cannot explain it to them because you do not understand it yourself. You could be in a room with 40 people but have completely lost sense of connection to all of them. The podcast also states an interesting paradox that while you want to be seen and be connected, you wear a permanent mask, hiding your illness and loneliness to not fall prey to any stigma, losing your sense of identity in the process. We try to find connections with people who accept us as we are and if we believe no one can do that, we become disconnected.

One all too prevalent phenomena that unfortunately comes into play within this context is stigma. Receiving a clinical diagnosis means you get put into a category and assigned a label that now becomes part of who you are. Whether we want to or not, we humans see the world in categories and associate stereotypical views with them. Stigma can significantly worsen the challenges associated with mental illness, especially when a diagnostic label emphasizes the ‘differentness’ of individuals with mental illness (Corrigan, 2007). It is important to consider whether we as a community and society might be partially at fault for the isolation and disconnection of those with clinical diagnoses.

“We try to find connections with people who accept us as we are and if we believe no one can do that, we become disconnected.”

But what can really be done to prevent those diagnosed with mental disorders from feeling isolated and lonely? Some direct interventions include changing maladaptive cognitions and social skills training (Mann et al., 2017). An example of a targeted maladaptive thought pattern would be negatively evaluating others, which reduces the possibility of creating relationships built on trust. Personally though, I find these interventions do not address the underlying issue of the lack of general understanding the individual’s environment. Other initiatives include wider community approaches, which consist of getting involved in community groups and projects. Though there has not been a significant body of evidence on this yet, I believe this takes a step in the right direction by possibly reducing stigma and encouraging conversation about mental health issues. Approaches such as improving employment opportunities also work towards creating a society in which social integration of those with clinical diagnoses is a reality.

Ultimately, loneliness is a complex problem, one that is particularly detrimental to those struggling with their mental health. While a logical answer might appear to offer and seek out social support, the experience of isolation often comes down to feeling like no one understands you. In my opinion, this speaks to a larger societal problem of a lack of awareness around mental health disorders. Although this is something that cannot be easily solved, a small step in the right direction would be attempting to create a collective understanding. Simply checking in on those you know might be struggling and repeatedly offering a genuine listening ear as to what their experience has been like might help. <<

References

– Alasmawi, K., Mann, F., Lewis, G., White, S., Mezey, G., & Lloyd‐Evans, B. (2020). To what extent does severity of loneliness vary among different mental health diagnostic groups: A cross‐sectional study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29(5), 921–934. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12727

– Corrigan, P. W. (2007). How clinical diagnosis might exacerbate the stigma of mental illness. Social Work, 52(1), 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/52.1.31

– Ikhtabi, S., Pitman, A., Toh, G., Birken, M., Pearce, E., & Johnson, S. (2022). The experience of loneliness among people with a “personality disorder” diagnosis or traits: a qualitative meta-synthesis. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-022-03767-9

– Loneliness and mental health – psych matters. (n.d.). Buzzsprout. https://psychmatters.ranzcp.org/1072258/12812102

– Ma, R., Wang, J., Lloyd‐Evans, B., Marston, L., & Johnson, S. (2021). Trajectories of loneliness and objective social isolation and associations between persistent loneliness and self-reported personal recovery in a cohort of secondary mental health service users in the UK. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03430-9

– Mann, F., Bone, J. K., Lloyd‐Evans, B., Frerichs, J., Pinfold, V., Ma, R., Wang, J., & Johnson, S. (2017). A life less lonely: the state of the art in interventions to reduce loneliness in people with mental health problems. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(6), 627–638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1392-y

– Meltzer, H., Bebbington, P., Dennis, M., Jenkins, R., McManus, S., & Brugha, T. (2012). Feelings of loneliness among adults with mental disorder. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0515-8

– Shiovitz-Ezra, S., & Ayalon, L. (2010). Situational versus chronic loneliness as risk factors for all-cause mortality. International Psychogeriatrics, 22(3), 455–462. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610209991426

– Wang, J., Mann, F., Lloyd‐Evans, B., Ma, R., & Johnson, S. (2018). Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1736-5

Several lines of research investigate the feeling of an intense disconnection from other people after receiving a mental health diagnosis. A study showed that loneliness was associated with six common mental disorders (generalized anxiety disorder, depression, OCD, phobia, panic disorder, mixed anxiety and depressive disorder), with the strongest link to depression (Meltzer et al., 2012). A qualitative meta-synthesis investigating loneliness in personality disorders found several important themes (Ikhtabi et al., 2022); namely disconnection and emptiness: a haunting alienation, alienation arising from childhood experiences; but also extended to existential and societal themes, such as recovery, embedded in a social world and experiences of existential loneliness. These themes highlight the multifaceted nature of loneliness, reflecting a complex interconnection between personal and societal factors. While we’ve all encountered loneliness at some stage, why is it significant to examine this phenomenon specifically within individuals diagnosed with mental health disorders?

Loneliness exerts a substantial toll on personal and societal health. It is a risk factor with consequences ranging from compromising physical health to increased suicide rates (Shiovitz-Ezra & Ayalon, 2010). Considering mental health problems, lower perceived social support is linked to increased symptom severity, diminished recovery, and poorer functional outcomes in those diagnosed with depression (Wang et al., 2018). The same article indicates that loneliness correlates with more pronounced anxiety and depressive symptoms. Greater loneliness of mental health service users is also directly linked to decreased rates of self-reported recovery (Ma et al., 2021). It is therefore not unreasonable to assume that loneliness aggravates the symptoms experienced across a wide range of disorders in general. As a silent adversary, the detrimental consequences of loneliness within this context emphasize the pressing need for suitable interventions and initiatives.

“As a silent adversary, the detrimental consequences of loneliness within this context emphasize the pressing need for suitable interventions and initiatives. ”

What exactly does it mean to be and feel lonely? Considering some personal accounts, the experience of loneliness fundamentally varies between individuals (Loneliness and Mental Health – Psych Matters, 2023). On a podcast episode of Psych Matters, Cat Drew, who has suffered from mental health problems and possible symptoms of psychosis since childhood, shares her personal account of what loneliness means to her. She describes it as a mismatch between how she experiences the world and how the world actually is. This contrasts the traditional perception of loneliness, that being lonely means being or feeling alone and socially isolated. Drew explains her illness allowed her ‘to always have someone to talk to, sometimes [they would] talk back, sometimes [they wouldn’t]’. Despite this, she always felt fundamentally disconnected from those around her.

Another perspective is shared by Paul Milne (Psych Matters, 2023), who was diagnosed with PTSD. For him, the experience of loneliness feels like you have lost your identity. Milne pointed out that though you may not physically be isolated, you feel alone. This is because your friends and family do not understand what is happening to you but worse than that, you cannot explain it to them because you do not understand it yourself. You could be in a room with 40 people but have completely lost sense of connection to all of them. The podcast also states an interesting paradox that while you want to be seen and be connected, you wear a permanent mask, hiding your illness and loneliness to not fall prey to any stigma, losing your sense of identity in the process. We try to find connections with people who accept us as we are and if we believe no one can do that, we become disconnected.

One all too prevalent phenomena that unfortunately comes into play within this context is stigma. Receiving a clinical diagnosis means you get put into a category and assigned a label that now becomes part of who you are. Whether we want to or not, we humans see the world in categories and associate stereotypical views with them. Stigma can significantly worsen the challenges associated with mental illness, especially when a diagnostic label emphasizes the ‘differentness’ of individuals with mental illness (Corrigan, 2007). It is important to consider whether we as a community and society might be partially at fault for the isolation and disconnection of those with clinical diagnoses.

“We try to find connections with people who accept us as we are and if we believe no one can do that, we become disconnected.”

But what can really be done to prevent those diagnosed with mental disorders from feeling isolated and lonely? Some direct interventions include changing maladaptive cognitions and social skills training (Mann et al., 2017). An example of a targeted maladaptive thought pattern would be negatively evaluating others, which reduces the possibility of creating relationships built on trust. Personally though, I find these interventions do not address the underlying issue of the lack of general understanding the individual’s environment. Other initiatives include wider community approaches, which consist of getting involved in community groups and projects. Though there has not been a significant body of evidence on this yet, I believe this takes a step in the right direction by possibly reducing stigma and encouraging conversation about mental health issues. Approaches such as improving employment opportunities also work towards creating a society in which social integration of those with clinical diagnoses is a reality.

Ultimately, loneliness is a complex problem, one that is particularly detrimental to those struggling with their mental health. While a logical answer might appear to offer and seek out social support, the experience of isolation often comes down to feeling like no one understands you. In my opinion, this speaks to a larger societal problem of a lack of awareness around mental health disorders. Although this is something that cannot be easily solved, a small step in the right direction would be attempting to create a collective understanding. Simply checking in on those you know might be struggling and repeatedly offering a genuine listening ear as to what their experience has been like might help. <<