The fantasy genre in books, films and games is beloved by both children and adults. Maybe this is because we seek a place where our imagination can roam around more freely than within the four walls of our rooms? Why, then, do so many fantasy pieces still revolve around the same themes of hardship that we try to avoid in the real world? Fantasy seems to give us more than just an easy escape, it gives us engaging worlds in which we can grow alongside our favourite characters.

The fantasy genre in books, films and games is beloved by both children and adults. Maybe this is because we seek a place where our imagination can roam around more freely than within the four walls of our rooms? Why, then, do so many fantasy pieces still revolve around the same themes of hardship that we try to avoid in the real world? Fantasy seems to give us more than just an easy escape, it gives us engaging worlds in which we can grow alongside our favourite characters.

Photo by Annie Spratt

Photo by Annie Spratt

Introducing fantasy by listing famous examples feels somewhat redundant – have the classics like The Chronicles of Narnia, the Harry Potter-series and The Lord of the Rings not already come to mind? Although these pieces are vastly different in their settings and characters, they’re all fantasy because the authors shared a dedication to creating expansive imaginary worlds with magical tools, creatures and powers.

Fantasy is a uniquely unrestricted genre, prompting literary critics Lewis and Irwing to nickname it “the literature of the impossible” (Lewis & Irwin, 1997). In realism, we expect the story to contain no speculative or supernatural elements. Even in Science Fiction narratives, we expect the imaginary elements to abide by the laws of physics, limited by the capabilities of the (given, much advanced) technologies. The very essence of fantasy, however, is the violation of norms that bind us to reality (ibid.). Trees can talk (Connolly, 2006), swallowing and burning metal gives you magic powers (Sanderson, 2006) and starlight allows you to manipulate time and space (Gladstone, 2012) – the motto “the sky is the limit” could not fit anyone better than fantasy creators.

This might be the reason why many literary and psychological analyses of the fantasy genre consider it the pinnacle of escapism (Hirschman, 1983). The latter can be defined as seeking out the safety and comfort of a fantasy world to distance oneself from the constraints of reality (APA, 2018). In other words, what we seek is the ability to dive into a world of complete freedom, magic and other impossibilities. In a recent Spiegeloog article, Zhecheva (2024) discussed how escapism can be detrimental or beneficial to our mental health, depending on whether we use it as a means of self-expansion or self-suppression. However, when I dove into the topic, the question arose if fantasy is truly as escapist as we think.

“If you consider that fantasy content is entirely unrestricted in theory, it is striking to see how the success of some pieces is predicted by the creators’ adherence to certain rules.”

If you consider that fantasy content is entirely unrestricted in theory, it is striking to see how the success of some pieces is predicted by the creators’ adherence to certain rules. Fantasy writer and writing coach Jed Herne dedicates his entire YouTube channel to the art of creating “good” fantasy, and he does not shy away from listing all the ‘Dos and Don’ts’, ‘Should and Shouldn’ts’ (Jed Herne, 2024). Surprisingly, these rules push creators to stick closer to reality. For example, writing coaches left and right agree that any good story should contain some sort of conflict or dispute, be it between a small number of characters or blatant warfare between entire nations and cultures. So if I consider myself a prospective fantasy writer, why am I not allowed to write a story where all characters are nice to one another, where there is everlasting peace and harmony? Would that not be the ideal escape from our reality which is characterised by its never-ending conflicts, ranging from daily little arguments to greater socio-political disagreements (StoryCastle, 2024)?

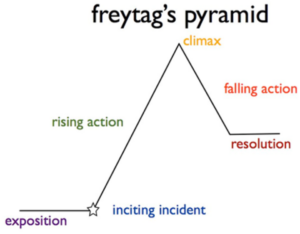

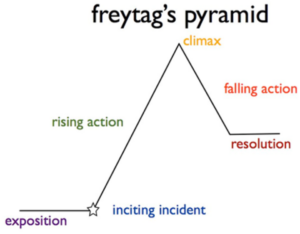

Writers of all kinds preach that conflict is the essential driver of a story, you hear it all the way from Freytag’s pyramid (Marx, 2012; originally 1863) to blog posts on Writers.com (Glatch, 2024a).

Freytag’s pyramid of drama structure; central is the climax which evolves from the set up of a conflict in the rising action. (Glatch, 2024b).

Why would we gravitate towards stories of conflict and arguments? Maybe it is related to our tendency to pay attention to, remember, and learn from negative events more than from positive ones. This well-established phenomenon is called the negativity bias (Vaish et al., 2008) which can be observed in people’s higher alertness to negative than to positive stimuli (Lewis et al., 2006), amongst other manifestations. You didn’t have to spell this out to journalists who have long caught on to the captivating effect of pessimistic headlines (Soroka & McAdams, 2015). Just like journalists, all kinds of content creators will eventually figure out that it is the negative tension of disagreement and conflict that keeps consumers engaged. Alright, so my fantasy story has to include some kind of conflict – but can’t I make my protagonist magnificent and almighty and have them solve all arising conflicts with a snap of their (magical) fingers? Wouldn’t that be a comforting escape from the moments in which I feel powerless and weak?

“In the same way, we might also feel like we are growing more resilient when we see our favourite characters suffer but persevere to the end, struggle but achieve their goal, lose hope but be reminded that they can make it through.”

Herne explains that we rarely see such omnipotent protagonists in practice because it is more satisfying to see a character earn their powers in hardship, trade them for another valuable possession, or only be able to use them under certain conditions (Jed Herne, 2024). In Fantasy author Brandon Sanderson agrees, stating that he is always more interested in a magic system’s limitations than its features (ibid.). Sometimes characters can only cast spells when the sun is out (Rawn, 1990), or they cannot use more magic than gives them brain damage (Aaronovitch, 2011). Herne suggests that we enjoy it when a magical system only operates under certain constraints because we derive pleasure from seeing characters work hard to find creative solutions within those constraints (ibid.). This might be due to effort justification, an effect by which we ascribe more value to the things whose acquisition cost us considerable effort (Klein et al., 2005) – in other words, if I work for something, it feels more meaningful.

On another note, some research suggests that we might even benefit from experiencing the hardship of others, a phenomenon termed vicarious resilience (Piccolino, 2022). Essentially, it was found that (mental) healthcare practitioners who work closely with trauma- or cancer-survivors can follow the example of their patients in developing self-care practices, keeping up hope and growing more resilient in the face of their hardships (ibid.). In the same way, we might also feel like we are growing more resilient when we see our favourite characters suffer but persevere to the end, struggle but achieve their goal, lose hope but be reminded that they can make it through.

Turns out that when we talk about escapism in fantasy, we must not equate this to a complete disregard and avoidance of reality. Fantasy stories reflect reality in many ways and these realistic elements are often the very reason why we are moved and touched by them. Even though we could escape into a world where magic and other imaginary elements make life harmonious and characters unconquerable, such a world does not seem to be the most appealing. We gain more from stories where conflicts and constraints force characters to work harder, motivating us to follow suit. Hopefully this will be the case when you consume your next piece of the captivating fantasy genre! <<

References

- Aaronovitch, B. (2011). Rivers of London. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rivers_of_London_(novel)

- American Psychological Association. (2018, April 19). Escapism. In APA dictionary of psychology. Retrieved September 21, 2024, from https://dictionary.apa.org/escapism

- Connolly, J. (2006). The Book of Lost Things. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Book_of_Lost_Things

- Fredericks, S. C., in Mullen, R. D., & Suvin, D. (1976). Science fiction Studies: Selected articles on science fiction, 1973-1975. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA18324786

- Gladstone, M. (2012). The Craft Sequence. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Craft_Sequence

- Glatch, S. (2024a, May 9). What is conflict in a story? Definition and examples [Blog post], retrieved October 6, 2024 from https://writers.com/what-is-conflict-in-a-story

- Glatch, S. (2024b, May 31). The 5 Elements of Dramatic Structure: Understanding Freytag’s Pyramid. Writers.com. https://writers.com/freytags-pyramid#gallery

- Hirschman, E. C. (1983). Predictors of Self-Projection, fantasy fulfillment, and escapism. The Journal of Social Psychology, 120(1), 63–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1983.9712011

- Jed Herne. (2024, April 26). 6 Magic system mistakes new fantasy writers make [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rrHtoux9zzQ

- Klein, E. D., Bhatt, R. S., & Zentall, T. R. (2005). Contrast and the justification of effort. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 12(2), 335–339. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03196381

- Lewis, P., Critchley, H., Rotshtein, P., & Dolan, R. (2006). Neural correlates of processing valence and arousal in affective words. Cerebral Cortex, 17(3), 742–748. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhk024

- Lewis, T. J., & Irwin, W. R. (1977). The Game of the Impossible: A rhetoric of fantasy. World Literature Today, 51(2), 338. https://doi.org/10.2307/40133559

- Marx, P. W. (2012). “Dramentheorie”. In Marx, Peter W. (ed.). Handbuch Drama : Theorie, Analyse, Geschichte (in German). Stuttgart/Weimar: Metzler. pp. 1–11. doi:10.1007/978-3-476-00512-0. ISBN 978-3-476-02348-3.

- Rawn, M. (1990). Sunrunner’s Fire. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sunrunner%27s_Fire

- Sanderson, B. (2006). Mistborn: The Final Empire. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mistborn:_The_Final_Empire

- Soroka, S., & McAdams, S. (2015). News, politics, and negativity. Political Communication, 32(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2014.881942

- StoryCastle. (2024, July 25). 5 WORLDBUILDING MISTAKES you don’t know you’re making (STOP THIS) [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=95AyKXSTJJM

- Piccolino, S. T. (2022) Vicarious resilience: traversing the path from client to clinician through a search for meaning, Social Work in Health Care, 61, 468-482. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2022.2134274

- Vaish, A., Grossmann, T., & Woodward, A. (2008). Not all emotions are created equal: The negativity bias in early socio-emotional development. Psychological Bulletin, 134. http://pubman.mpdl.mpg.de/pubman/item/escidoc:1836173

- Zecheva, E., (2024). Gradients and Pitfalls of Escaping Reality [Blogpost]. https://www.spiegeloog.amsterdam/gradients-and-pitfalls-of-escaping-reality/

Introducing fantasy by listing famous examples feels somewhat redundant – have the classics like The Chronicles of Narnia, the Harry Potter-series and The Lord of the Rings not already come to mind? Although these pieces are vastly different in their settings and characters, they’re all fantasy because the authors shared a dedication to creating expansive imaginary worlds with magical tools, creatures and powers.

Fantasy is a uniquely unrestricted genre, prompting literary critics Lewis and Irwing to nickname it “the literature of the impossible” (Lewis & Irwin, 1997). In realism, we expect the story to contain no speculative or supernatural elements. Even in Science Fiction narratives, we expect the imaginary elements to abide by the laws of physics, limited by the capabilities of the (given, much advanced) technologies. The very essence of fantasy, however, is the violation of norms that bind us to reality (ibid.). Trees can talk (Connolly, 2006), swallowing and burning metal gives you magic powers (Sanderson, 2006) and starlight allows you to manipulate time and space (Gladstone, 2012) – the motto “the sky is the limit” could not fit anyone better than fantasy creators.

This might be the reason why many literary and psychological analyses of the fantasy genre consider it the pinnacle of escapism (Hirschman, 1983). The latter can be defined as seeking out the safety and comfort of a fantasy world to distance oneself from the constraints of reality (APA, 2018). In other words, what we seek is the ability to dive into a world of complete freedom, magic and other impossibilities. In a recent Spiegeloog article, Zhecheva (2024) discussed how escapism can be detrimental or beneficial to our mental health, depending on whether we use it as a means of self-expansion or self-suppression. However, when I dove into the topic, the question arose if fantasy is truly as escapist as we think.

“If you consider that fantasy content is entirely unrestricted in theory, it is striking to see how the success of some pieces is predicted by the creators’ adherence to certain rules.”

If you consider that fantasy content is entirely unrestricted in theory, it is striking to see how the success of some pieces is predicted by the creators’ adherence to certain rules. Fantasy writer and writing coach Jed Herne dedicates his entire YouTube channel to the art of creating “good” fantasy, and he does not shy away from listing all the ‘Dos and Don’ts’, ‘Should and Shouldn’ts’ (Jed Herne, 2024). Surprisingly, these rules push creators to stick closer to reality. For example, writing coaches left and right agree that any good story should contain some sort of conflict or dispute, be it between a small number of characters or blatant warfare between entire nations and cultures. So if I consider myself a prospective fantasy writer, why am I not allowed to write a story where all characters are nice to one another, where there is everlasting peace and harmony? Would that not be the ideal escape from our reality which is characterised by its never-ending conflicts, ranging from daily little arguments to greater socio-political disagreements (StoryCastle, 2024)?

Writers of all kinds preach that conflict is the essential driver of a story, you hear it all the way from Freytag’s pyramid (Marx, 2012; originally 1863) to blog posts on Writers.com (Glatch, 2024a).

Freytag’s pyramid of drama structure; central is the climax which evolves from the set up of a conflict in the rising action. (Glatch, 2024b).

Why would we gravitate towards stories of conflict and arguments? Maybe it is related to our tendency to pay attention to, remember, and learn from negative events more than from positive ones. This well-established phenomenon is called the negativity bias (Vaish et al., 2008) which can be observed in people’s higher alertness to negative than to positive stimuli (Lewis et al., 2006), amongst other manifestations. You didn’t have to spell this out to journalists who have long caught on to the captivating effect of pessimistic headlines (Soroka & McAdams, 2015). Just like journalists, all kinds of content creators will eventually figure out that it is the negative tension of disagreement and conflict that keeps consumers engaged. Alright, so my fantasy story has to include some kind of conflict – but can’t I make my protagonist magnificent and almighty and have them solve all arising conflicts with a snap of their (magical) fingers? Wouldn’t that be a comforting escape from the moments in which I feel powerless and weak?

“In the same way, we might also feel like we are growing more resilient when we see our favourite characters suffer but persevere to the end, struggle but achieve their goal, lose hope but be reminded that they can make it through.”

Herne explains that we rarely see such omnipotent protagonists in practice because it is more satisfying to see a character earn their powers in hardship, trade them for another valuable possession, or only be able to use them under certain conditions (Jed Herne, 2024). In Fantasy author Brandon Sanderson agrees, stating that he is always more interested in a magic system’s limitations than its features (ibid.). Sometimes characters can only cast spells when the sun is out (Rawn, 1990), or they cannot use more magic than gives them brain damage (Aaronovitch, 2011). Herne suggests that we enjoy it when a magical system only operates under certain constraints because we derive pleasure from seeing characters work hard to find creative solutions within those constraints (ibid.). This might be due to effort justification, an effect by which we ascribe more value to the things whose acquisition cost us considerable effort (Klein et al., 2005) – in other words, if I work for something, it feels more meaningful.

On another note, some research suggests that we might even benefit from experiencing the hardship of others, a phenomenon termed vicarious resilience (Piccolino, 2022). Essentially, it was found that (mental) healthcare practitioners who work closely with trauma- or cancer-survivors can follow the example of their patients in developing self-care practices, keeping up hope and growing more resilient in the face of their hardships (ibid.). In the same way, we might also feel like we are growing more resilient when we see our favourite characters suffer but persevere to the end, struggle but achieve their goal, lose hope but be reminded that they can make it through.

Turns out that when we talk about escapism in fantasy, we must not equate this to a complete disregard and avoidance of reality. Fantasy stories reflect reality in many ways and these realistic elements are often the very reason why we are moved and touched by them. Even though we could escape into a world where magic and other imaginary elements make life harmonious and characters unconquerable, such a world does not seem to be the most appealing. We gain more from stories where conflicts and constraints force characters to work harder, motivating us to follow suit. Hopefully this will be the case when you consume your next piece of the captivating fantasy genre! <<

References

- Aaronovitch, B. (2011). Rivers of London. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rivers_of_London_(novel)

- American Psychological Association. (2018, April 19). Escapism. In APA dictionary of psychology. Retrieved September 21, 2024, from https://dictionary.apa.org/escapism

- Connolly, J. (2006). The Book of Lost Things. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Book_of_Lost_Things

- Fredericks, S. C., in Mullen, R. D., & Suvin, D. (1976). Science fiction Studies: Selected articles on science fiction, 1973-1975. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA18324786

- Gladstone, M. (2012). The Craft Sequence. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Craft_Sequence

- Glatch, S. (2024a, May 9). What is conflict in a story? Definition and examples [Blog post], retrieved October 6, 2024 from https://writers.com/what-is-conflict-in-a-story

- Glatch, S. (2024b, May 31). The 5 Elements of Dramatic Structure: Understanding Freytag’s Pyramid. Writers.com. https://writers.com/freytags-pyramid#gallery

- Hirschman, E. C. (1983). Predictors of Self-Projection, fantasy fulfillment, and escapism. The Journal of Social Psychology, 120(1), 63–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.1983.9712011

- Jed Herne. (2024, April 26). 6 Magic system mistakes new fantasy writers make [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rrHtoux9zzQ

- Klein, E. D., Bhatt, R. S., & Zentall, T. R. (2005). Contrast and the justification of effort. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 12(2), 335–339. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03196381

- Lewis, P., Critchley, H., Rotshtein, P., & Dolan, R. (2006). Neural correlates of processing valence and arousal in affective words. Cerebral Cortex, 17(3), 742–748. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhk024

- Lewis, T. J., & Irwin, W. R. (1977). The Game of the Impossible: A rhetoric of fantasy. World Literature Today, 51(2), 338. https://doi.org/10.2307/40133559

- Marx, P. W. (2012). “Dramentheorie”. In Marx, Peter W. (ed.). Handbuch Drama : Theorie, Analyse, Geschichte (in German). Stuttgart/Weimar: Metzler. pp. 1–11. doi:10.1007/978-3-476-00512-0. ISBN 978-3-476-02348-3.

- Rawn, M. (1990). Sunrunner’s Fire. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sunrunner%27s_Fire

- Sanderson, B. (2006). Mistborn: The Final Empire. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mistborn:_The_Final_Empire

- Soroka, S., & McAdams, S. (2015). News, politics, and negativity. Political Communication, 32(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2014.881942

- StoryCastle. (2024, July 25). 5 WORLDBUILDING MISTAKES you don’t know you’re making (STOP THIS) [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=95AyKXSTJJM

- Piccolino, S. T. (2022) Vicarious resilience: traversing the path from client to clinician through a search for meaning, Social Work in Health Care, 61, 468-482. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2022.2134274

- Vaish, A., Grossmann, T., & Woodward, A. (2008). Not all emotions are created equal: The negativity bias in early socio-emotional development. Psychological Bulletin, 134. http://pubman.mpdl.mpg.de/pubman/item/escidoc:1836173

- Zecheva, E., (2024). Gradients and Pitfalls of Escaping Reality [Blogpost]. https://www.spiegeloog.amsterdam/gradients-and-pitfalls-of-escaping-reality/