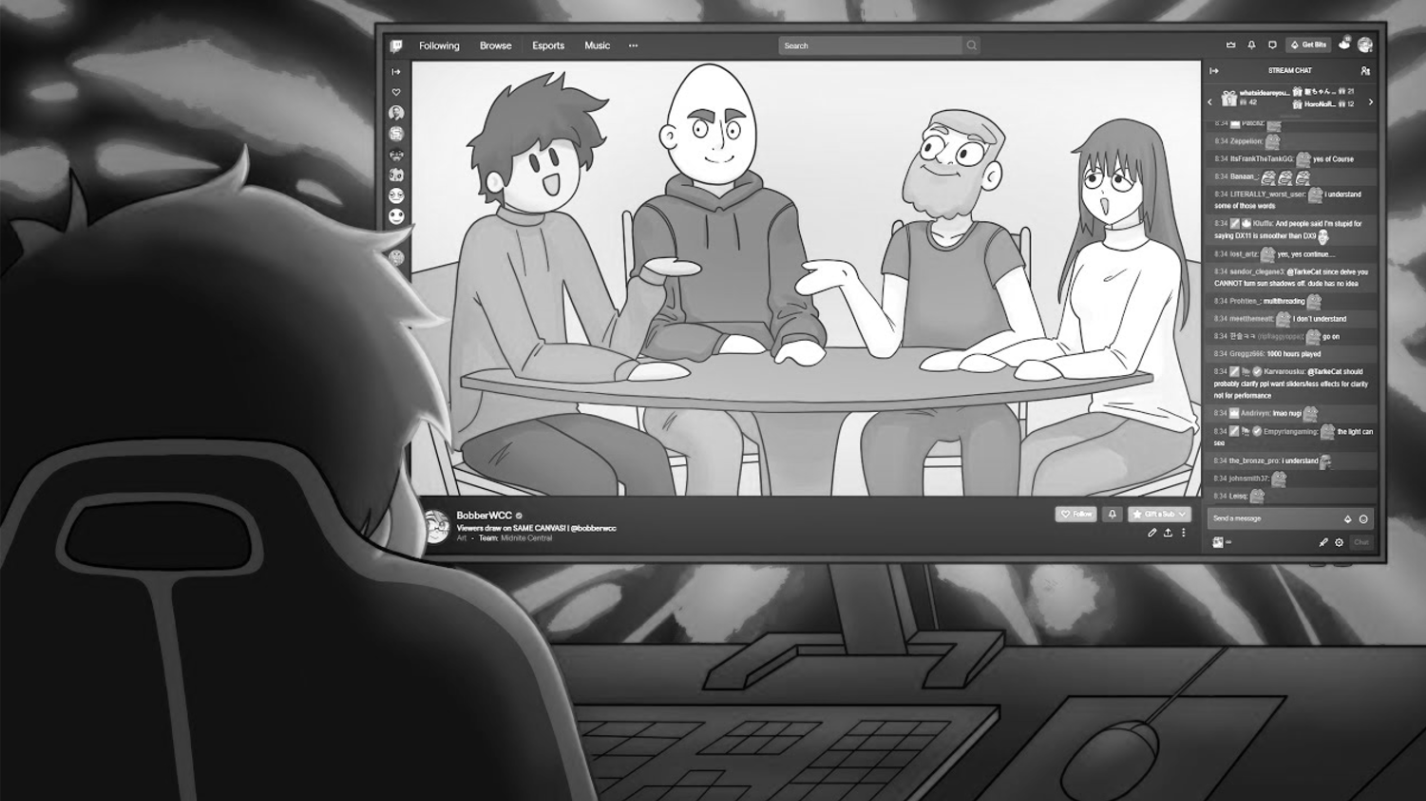

Imagine pouring your time, money, and heart into a relationship where every word spoken to you is broadcast to an audience of thousands – welcome to the strange and rapidly growing world of parasocial relationships on Twitch.

Imagine pouring your time, money, and heart into a relationship where every word spoken to you is broadcast to an audience of thousands – welcome to the strange and rapidly growing world of parasocial relationships on Twitch.

Understanding Parasocial Relationships

The term parasocial relationship (PSR) was coined by anthropologist Donald Horton and sociologist R. Richard Wohl in 1956 as a description of the one-sided relationship that media users form due to exposure to media personalities, who remain oblivious to the user’s existence (Handwiki, 2022). Horton and Wohl argued that PSRs are born from the accumulation of several parasocial interactions, a singular exposure that garners interest in a persona, which results in an emotional and cognitive connection that persists due to the resulting development of illusions of intimacy, friendship, and identification (Schramm, 2015).

The Impacts of Social Media

The rise of social media, including live-streaming platforms like Twitch, has transformed PSRs into something far more complex. In the modern age of live streaming, millions of viewers log onto Twitch, spending countless hours engaged within a highly immersive, digitally mediated ecosystem centered around streamers they’ll likely never meet. They listen to their thoughts, laugh at their jokes, and sometimes even feel a deep personal connection towards these content creators. The characteristics underpinning these uniquely novel social interactions have shifted the nature of PSRs away from the classic one-sided relationship, and towards a “one-and-a-half” sided relationship. These relationships differ in their potential for reciprocal communication and are characterized by strong community affiliation, fandom cultures, intense emotional involvement, and heightened immersion (Kowert & Daniel, 2021). Unlike traditional media figures, these streamers might engage with the audience through chat interactions or by acknowledging donations, but this does not establish a genuine reciprocal relationship. This partial reciprocity intensifies the emotional commitment of the user, culminating in the creation of a bond that feels more authentic and personal than a conventional PSR. The ambiguous nature of the roles within this fan-model dynamic often results in a blurring of fantasy and reality, leading to potential boundary violations and problematic fan-streamer interactions, which can, in turn, have deeply negative psychological impacts on the viewer (Tynan & Linehan, 2024).

“These uniquely novel social interactions have shifted the nature of PSRs away from the classic one-sided relationship, and towards a “one-and-a-half” sided relationship.”

The Formation and Maintenance of Parasocial Relationships on Twitch

At the heart of these PSRs on Twitch is the illusion of intimacy – a perception of a close personal bond between the viewer and streamer – a mechanism that promotes deep emotional involvement, despite the absence of a true reciprocal relationship. The viewer may feel that they ‘know’ the streamer intimately even though their interactions are heavily mediated and one-sided. Like traditional PSRs, accumulating singular parasocial interactions (PSIs) proportionally strengthens the illusions of intimacy experienced within the relationship. A PSI can occur, in a more traditional sense, when the viewer perceives a direct interaction with the streamer, even if they are addressing a vast and anonymous audience. However, PSIs can also take on a distinctly different form, where the streamer also acknowledges the viewer’s gaze. The cumulation of these two forms of PSIs allows for the formation of a far more profound PSR, as the experience of being seen has a greater psychological impact than merely observing. This can be illustrated with the Social Presence Theory (Short, Williams, & Christie, 1976), which posits that the degree to which individuals perceive the presence of others during communication significantly influences relational dynamics (Calefato & Lanubile, 2010). Within this context, interactions that incorporate both the viewer’s observation and the streamer’s acknowledgment create a heightened sense of social presence and convey a richer and more diverse array of visual and verbal cues – such as the streamer’s live gaze directed at the camera, their expressive body language, and the nuances of their voice intonation – compared to traditional PSR, which lack this constant real-time engagement (Calefato & Lanubile, 2010). As a result, this medium enables a more satisfying and meaningful interpersonal relationship. Imagine if your favorite actor suddenly broke the fourth wall, turned towards the camera, and acknowledged your presence – wouldn’t you feel a stronger sense of personal attachment?

This heightened sense of social presence also amplifies the effects of minimal reciprocity, where the sporadic acknowledgment from the streamer enhances the viewer’s emotional engagement through a cycle of intermittent reinforcement. Within the concept of operant conditioning, intermittent reinforcement are schedules in which a particular behavior produces a particular consequence, but not every time the behavior occurs (Tarbox & Tarbox, 2017). Applying this concept to the viewer-streamer relationship dynamic, when viewers engage with the chat or contribute through donations, they receive an acknowledgment from the streamer sporadically rather than consistently. This can in turn produce a sense of anticipatory excitement, compelling viewers to remain actively involved in hopes of receiving the self-perceived reward of recognition. Such unpredictability promotes an uncertain reward system, leading to stronger behavioral reinforcement compared to the predictable outcome of consistent recognition (Skinner, 1963). The cycle continues, increasing the likelihood of continued engagement, further fostering the production of a greater number of parasocial interactions which in turn strengthens the PSR. The cyclical nature of engagement and reward not only solidifies the viewer’s connection to the streamer but also establishes a framework for understanding why these “one-and-a-half” sided PSRs can be particularly strong and enduring over time.

“Escapism makes a lot of intuitive sense – whisk people away from their cares with stories of a better life (Adam Cohen)”

The Psychological Impacts of Twitch Parasocial Relationships

As we consider the depth of these emotional investments, it becomes crucial to examine the potential psychological impacts associated with such intense PSRs. Can the comfort of a PSR ever replace the warmth of a genuine friendship? Prolonged engagement in these dynamics can lead to social isolation, negative social outcomes due to reduced real-world interaction, and a diminishment in self-esteem. Psychiatrist Dr. Kanojia, a leading expert in the psychological dynamics of Twitch and its impact on viewer behavior, argues that PSRs formed through Twitch can significantly contribute to social isolation, as individuals often turn to these interactions as a means of fulfilling their innate need for connection whilst simultaneously avoiding real-life social engagement (L., 2021). Individuals most receptive to PSRs are those who have past traumatic experiences, particularly from abusive or broken homes. They may develop insecure attachment styles, resulting in a hesitancy to engage in genuine human connections (Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., 2016). Twitch in this case offers a seemingly safe alternative, facilitating engagement while minimizing the risk of psychological distress. The increased investment in the lives of streamers can prompt viewers to live vicariously through them. The emotional highs and lows associated with the streamers’ successes and failures create a sense of purpose and attachment. When conflict arises between streamers, viewers may often experience these disagreements as personal attacks, exacerbating feelings of social isolation. This can trigger individuals to turn inwards as opposed to seeking support from real-life relationships, further entrenching themselves into the digital world. Dependence on Twitch as a primary source of connection has been observed to function as a form of escapism, with a November 2020 survey indicating that live streams help viewers cope with challenging periods (de Wit, van der Kraan, & Theeuwes, 2020). However, this temporary escape is a double-edged sword; it may simultaneously lead to a superficial sense of fulfillment, ultimately discouraging viewers from cultivating meaningful real-world relationships.

Beyond the risks of social isolation, Twitch PSRs may also affect self-esteem. Garcia et al. (2022) tested the Multidimensional Measure of Parasocial Relationships on the complex ways in which individuals’ commitment to these PSRs correlates with negative self-perception. The more deeply individuals engaged in PSRs, the more likely they were to engage in social comparison, which significantly lowered their self-esteem. Due to the high levels of emotional engagement and commitment within Twitch PSRs, we can infer that these implications on self-esteem may be even more pronounced for Twitch viewers. One possible explanation may be gauged with reference to the Social Comparison Theory (Festinger, 1954), which suggests that people determine their social and personal worth by comparing themselves to others. As viewers engage closely with streamers, they are more likely to make upward social comparisons with the curated, often idealized lives of streamers. The additional sense of intimacy resulting from the distinguishing “one-and-a-half” sided Twitch PSR may intensify these comparisons, resulting in a proportional relationship between the depth of emotional commitment and the extent of self-esteem decline, with viewers most deeply involved in these parasocial interactions being particularly vulnerable to negative self-perception.

In an age where digital connections often overshadow real-world interactions, understanding the complexities of PSRs on platforms like Twitch has never been more critical. It remains crucial to acknowledge the rapid change in the theoretical nature of these relationships from traditional one-sided dynamics, where viewers engaged passively with media figures, to a more complex “one-and-a-half” sided model. Whilst these relationships can provide viewers with a sense of intimacy and community, one must remain cognizant of the potential psychological challenges. The illusions of intimacy, as fostered through social presence and intermittent reinforcement, facilitate the development of superficial bonds. As viewers become increasingly entwined in the lives of streamers, social isolation, and diminished self-esteem are likely. It is imperative for both viewers and streamers to recognize these dynamics, ensuring that digital connections foster genuine community whilst safeguarding against the emotional pitfalls that may arise from misplaced intimacy. Let us remain vigilant in our pursuit of authentic connections, ensuring that the bonds we forge online do not eclipse the richness of the relationships in store for us within the real world. <<

References

- Calefato, F., & Lanubile, F. (2010). Chapter 6 – Communication Media Selection for Remote Interaction of Ad Hoc Groups. Advances in Computers: Improving the Web, 78, pp. 271-313. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0065245810780062

- Cohen, A. (2009, October 16). ‘Mad Men’ and the Thrill of Other People’s Misery in Sour Times. (The New York Times) Retrieved October 2024, from The New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/17/opinion/17sat4.html?em

- de Wit, J., van der Kraan, A., & Theeuwes, J. (2020). Live Streams on Twitch Help Viewers Cope With Difficult Periods in Life. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. Retrieved from https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.586975

- Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. (2016, August 30). Attatchment Theory. (i. Encyclopædia Britannica, Producer) Retrieved October 2024, from Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/science/attachment-theory

- Festinger, L. (1954). A Theory of Social Comparison Processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117-140. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202

- Garcia, D., Björk, E., & Kazemitabar, M. (2022). The A(ffect) B(ehavior) C(ognition) D(ecision) of parasocial relationships: A pilot study on the psychometric properties of the Multidimensional Measure of Parasocial Relationships (MMPR). Heliyon, 8(10), e10779. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405844022020679

- Glink. (2020, July 3). The Parasocial Problem with Livestreaming. Retrieved October 2024, from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=GvYAVti8nbk&ab_channel=Glink

- Handwiki. (2022, November 24). Parasocial Relationships. (Handwiki, Producer) Retrieved October 2024, from Encyclopedia: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/36306

- Kowert, R., & Daniel, E. (2021). The one-and-a-half sided parasocial relationship: The curious case of live streaming. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 4, 100150. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2451958821000981

- L., K. (2021, July 15). Parasocial relationships on twitch: A Psychiatrist’s perspective. Retrieved October 2024, from Healthy Gamer: https://www.healthygamer.gg/blog/parasocial-relationships-on-twitch-a-psychiatrists-perspective

- Schramm, H. (2015). Parasocial Interactions and Relationships. In The International Encyclopedia of Communication. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781405186407.wbiecp006.pub2

- Short, J., Williams, E., & Christie, B. (1976). The Social Psychology of Telecommunications. Wiley. Retrieved from https://books.google.nl/books?id=Ze63AAAAIAAJ

- Skinner, B. (1963). Operant behavior. American Psychologist, 18(8), 503–515. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1037/h0045185

- Tarbox, J., & Tarbox, C. (2017). Chapter 5 – Skill Acquisition. (J. Tarbox, & C. Tarbox, Eds.) Training Manual for Behavior Technicians Working with Individuals with Autism, pp. 47-87. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128094082000052

- Tynan, L., & Linehan, C. (2024). OnlyFans: How Models Negotiate Fan Interaction. Sexuality \& Culture, 28(5), 2289–2322. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-024-10230-2

Understanding Parasocial Relationships

The term parasocial relationship (PSR) was coined by anthropologist Donald Horton and sociologist R. Richard Wohl in 1956 as a description of the one-sided relationship that media users form due to exposure to media personalities, who remain oblivious to the user’s existence (Handwiki, 2022). Horton and Wohl argued that PSRs are born from the accumulation of several parasocial interactions, a singular exposure that garners interest in a persona, which results in an emotional and cognitive connection that persists due to the resulting development of illusions of intimacy, friendship, and identification (Schramm, 2015).

The Impacts of Social Media

The rise of social media, including live-streaming platforms like Twitch, has transformed PSRs into something far more complex. In the modern age of live streaming, millions of viewers log onto Twitch, spending countless hours engaged within a highly immersive, digitally mediated ecosystem centered around streamers they’ll likely never meet. They listen to their thoughts, laugh at their jokes, and sometimes even feel a deep personal connection towards these content creators. The characteristics underpinning these uniquely novel social interactions have shifted the nature of PSRs away from the classic one-sided relationship, and towards a “one-and-a-half” sided relationship. These relationships differ in their potential for reciprocal communication and are characterized by strong community affiliation, fandom cultures, intense emotional involvement, and heightened immersion (Kowert & Daniel, 2021). Unlike traditional media figures, these streamers might engage with the audience through chat interactions or by acknowledging donations, but this does not establish a genuine reciprocal relationship. This partial reciprocity intensifies the emotional commitment of the user, culminating in the creation of a bond that feels more authentic and personal than a conventional PSR. The ambiguous nature of the roles within this fan-model dynamic often results in a blurring of fantasy and reality, leading to potential boundary violations and problematic fan-streamer interactions, which can, in turn, have deeply negative psychological impacts on the viewer (Tynan & Linehan, 2024).

“These uniquely novel social interactions have shifted the nature of PSRs away from the classic one-sided relationship, and towards a “one-and-a-half” sided relationship.”

The Formation and Maintenance of Parasocial Relationships on Twitch

At the heart of these PSRs on Twitch is the illusion of intimacy – a perception of a close personal bond between the viewer and streamer – a mechanism that promotes deep emotional involvement, despite the absence of a true reciprocal relationship. The viewer may feel that they ‘know’ the streamer intimately even though their interactions are heavily mediated and one-sided. Like traditional PSRs, accumulating singular parasocial interactions (PSIs) proportionally strengthens the illusions of intimacy experienced within the relationship. A PSI can occur, in a more traditional sense, when the viewer perceives a direct interaction with the streamer, even if they are addressing a vast and anonymous audience. However, PSIs can also take on a distinctly different form, where the streamer also acknowledges the viewer’s gaze. The cumulation of these two forms of PSIs allows for the formation of a far more profound PSR, as the experience of being seen has a greater psychological impact than merely observing. This can be illustrated with the Social Presence Theory (Short, Williams, & Christie, 1976), which posits that the degree to which individuals perceive the presence of others during communication significantly influences relational dynamics (Calefato & Lanubile, 2010). Within this context, interactions that incorporate both the viewer’s observation and the streamer’s acknowledgment create a heightened sense of social presence and convey a richer and more diverse array of visual and verbal cues – such as the streamer’s live gaze directed at the camera, their expressive body language, and the nuances of their voice intonation – compared to traditional PSR, which lack this constant real-time engagement (Calefato & Lanubile, 2010). As a result, this medium enables a more satisfying and meaningful interpersonal relationship. Imagine if your favorite actor suddenly broke the fourth wall, turned towards the camera, and acknowledged your presence – wouldn’t you feel a stronger sense of personal attachment?

This heightened sense of social presence also amplifies the effects of minimal reciprocity, where the sporadic acknowledgment from the streamer enhances the viewer’s emotional engagement through a cycle of intermittent reinforcement. Within the concept of operant conditioning, intermittent reinforcement are schedules in which a particular behavior produces a particular consequence, but not every time the behavior occurs (Tarbox & Tarbox, 2017). Applying this concept to the viewer-streamer relationship dynamic, when viewers engage with the chat or contribute through donations, they receive an acknowledgment from the streamer sporadically rather than consistently. This can in turn produce a sense of anticipatory excitement, compelling viewers to remain actively involved in hopes of receiving the self-perceived reward of recognition. Such unpredictability promotes an uncertain reward system, leading to stronger behavioral reinforcement compared to the predictable outcome of consistent recognition (Skinner, 1963). The cycle continues, increasing the likelihood of continued engagement, further fostering the production of a greater number of parasocial interactions which in turn strengthens the PSR. The cyclical nature of engagement and reward not only solidifies the viewer’s connection to the streamer but also establishes a framework for understanding why these “one-and-a-half” sided PSRs can be particularly strong and enduring over time.

“Escapism makes a lot of intuitive sense – whisk people away from their cares with stories of a better life (Adam Cohen)”

The Psychological Impacts of Twitch Parasocial Relationships

As we consider the depth of these emotional investments, it becomes crucial to examine the potential psychological impacts associated with such intense PSRs. Can the comfort of a PSR ever replace the warmth of a genuine friendship? Prolonged engagement in these dynamics can lead to social isolation, negative social outcomes due to reduced real-world interaction, and a diminishment in self-esteem. Psychiatrist Dr. Kanojia, a leading expert in the psychological dynamics of Twitch and its impact on viewer behavior, argues that PSRs formed through Twitch can significantly contribute to social isolation, as individuals often turn to these interactions as a means of fulfilling their innate need for connection whilst simultaneously avoiding real-life social engagement (L., 2021). Individuals most receptive to PSRs are those who have past traumatic experiences, particularly from abusive or broken homes. They may develop insecure attachment styles, resulting in a hesitancy to engage in genuine human connections (Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., 2016). Twitch in this case offers a seemingly safe alternative, facilitating engagement while minimizing the risk of psychological distress. The increased investment in the lives of streamers can prompt viewers to live vicariously through them. The emotional highs and lows associated with the streamers’ successes and failures create a sense of purpose and attachment. When conflict arises between streamers, viewers may often experience these disagreements as personal attacks, exacerbating feelings of social isolation. This can trigger individuals to turn inwards as opposed to seeking support from real-life relationships, further entrenching themselves into the digital world. Dependence on Twitch as a primary source of connection has been observed to function as a form of escapism, with a November 2020 survey indicating that live streams help viewers cope with challenging periods (de Wit, van der Kraan, & Theeuwes, 2020). However, this temporary escape is a double-edged sword; it may simultaneously lead to a superficial sense of fulfillment, ultimately discouraging viewers from cultivating meaningful real-world relationships.

Beyond the risks of social isolation, Twitch PSRs may also affect self-esteem. Garcia et al. (2022) tested the Multidimensional Measure of Parasocial Relationships on the complex ways in which individuals’ commitment to these PSRs correlates with negative self-perception. The more deeply individuals engaged in PSRs, the more likely they were to engage in social comparison, which significantly lowered their self-esteem. Due to the high levels of emotional engagement and commitment within Twitch PSRs, we can infer that these implications on self-esteem may be even more pronounced for Twitch viewers. One possible explanation may be gauged with reference to the Social Comparison Theory (Festinger, 1954), which suggests that people determine their social and personal worth by comparing themselves to others. As viewers engage closely with streamers, they are more likely to make upward social comparisons with the curated, often idealized lives of streamers. The additional sense of intimacy resulting from the distinguishing “one-and-a-half” sided Twitch PSR may intensify these comparisons, resulting in a proportional relationship between the depth of emotional commitment and the extent of self-esteem decline, with viewers most deeply involved in these parasocial interactions being particularly vulnerable to negative self-perception.

In an age where digital connections often overshadow real-world interactions, understanding the complexities of PSRs on platforms like Twitch has never been more critical. It remains crucial to acknowledge the rapid change in the theoretical nature of these relationships from traditional one-sided dynamics, where viewers engaged passively with media figures, to a more complex “one-and-a-half” sided model. Whilst these relationships can provide viewers with a sense of intimacy and community, one must remain cognizant of the potential psychological challenges. The illusions of intimacy, as fostered through social presence and intermittent reinforcement, facilitate the development of superficial bonds. As viewers become increasingly entwined in the lives of streamers, social isolation, and diminished self-esteem are likely. It is imperative for both viewers and streamers to recognize these dynamics, ensuring that digital connections foster genuine community whilst safeguarding against the emotional pitfalls that may arise from misplaced intimacy. Let us remain vigilant in our pursuit of authentic connections, ensuring that the bonds we forge online do not eclipse the richness of the relationships in store for us within the real world. <<

References

- Calefato, F., & Lanubile, F. (2010). Chapter 6 – Communication Media Selection for Remote Interaction of Ad Hoc Groups. Advances in Computers: Improving the Web, 78, pp. 271-313. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0065245810780062

- Cohen, A. (2009, October 16). ‘Mad Men’ and the Thrill of Other People’s Misery in Sour Times. (The New York Times) Retrieved October 2024, from The New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2009/10/17/opinion/17sat4.html?em

- de Wit, J., van der Kraan, A., & Theeuwes, J. (2020). Live Streams on Twitch Help Viewers Cope With Difficult Periods in Life. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. Retrieved from https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychology/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.586975

- Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. (2016, August 30). Attatchment Theory. (i. Encyclopædia Britannica, Producer) Retrieved October 2024, from Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/science/attachment-theory

- Festinger, L. (1954). A Theory of Social Comparison Processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117-140. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202

- Garcia, D., Björk, E., & Kazemitabar, M. (2022). The A(ffect) B(ehavior) C(ognition) D(ecision) of parasocial relationships: A pilot study on the psychometric properties of the Multidimensional Measure of Parasocial Relationships (MMPR). Heliyon, 8(10), e10779. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2405844022020679

- Glink. (2020, July 3). The Parasocial Problem with Livestreaming. Retrieved October 2024, from YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=GvYAVti8nbk&ab_channel=Glink

- Handwiki. (2022, November 24). Parasocial Relationships. (Handwiki, Producer) Retrieved October 2024, from Encyclopedia: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/36306

- Kowert, R., & Daniel, E. (2021). The one-and-a-half sided parasocial relationship: The curious case of live streaming. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 4, 100150. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2451958821000981

- L., K. (2021, July 15). Parasocial relationships on twitch: A Psychiatrist’s perspective. Retrieved October 2024, from Healthy Gamer: https://www.healthygamer.gg/blog/parasocial-relationships-on-twitch-a-psychiatrists-perspective

- Schramm, H. (2015). Parasocial Interactions and Relationships. In The International Encyclopedia of Communication. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781405186407.wbiecp006.pub2

- Short, J., Williams, E., & Christie, B. (1976). The Social Psychology of Telecommunications. Wiley. Retrieved from https://books.google.nl/books?id=Ze63AAAAIAAJ

- Skinner, B. (1963). Operant behavior. American Psychologist, 18(8), 503–515. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1037/h0045185

- Tarbox, J., & Tarbox, C. (2017). Chapter 5 – Skill Acquisition. (J. Tarbox, & C. Tarbox, Eds.) Training Manual for Behavior Technicians Working with Individuals with Autism, pp. 47-87. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128094082000052

- Tynan, L., & Linehan, C. (2024). OnlyFans: How Models Negotiate Fan Interaction. Sexuality \& Culture, 28(5), 2289–2322. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-024-10230-2