The Matrix. Black Mirror. Terminator. The cautionary tale of a technological takeover of the world has been told from the moment the word ‘robot’ was first spoken. But while these stories nurtured the apprehension that follows one metallic step after the other, they may have also been the Trojan horse that allowed such technology to quietly seep into our lives. Artificial Intelligence is not a Marvel villain, it is the aliens with jobs from Men In Black.

The Matrix. Black Mirror. Terminator. The cautionary tale of a technological takeover of the world has been told from the moment the word ‘robot’ was first spoken. But while these stories nurtured the apprehension that follows one metallic step after the other, they may have also been the Trojan horse that allowed such technology to quietly seep into our lives. Artificial Intelligence is not a Marvel villain, it is the aliens with jobs from Men In Black.

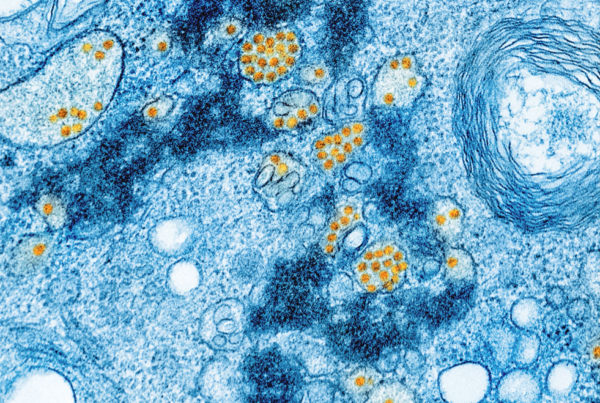

Fahrenheit 451’s Mechanical Hound is closer than we think.

Photo Source: Throwflame

Fahrenheit 451’s Mechanical Hound is closer than we think.

Photo Source: Throwflame

From the genesis of the ‘robot’ in Karel Čapek’s Rossum’s Universal Robots, the path of Artificial Intelligence and its future alongside humans has been a complicated one to piece together. Mankind’s fascination with the catastrophe an intelligent entity could bring about has left a vivid trail of disaster stories detailing the many ways that A.I. could destroy, turn against, or even surpass us. However, in a society becoming ever more aware of the strain brought onto us by the technology all around us, we are left wondering how such oppressive systems (Hynes, 2021) slipped past us despite our caution. The answer lies somewhere within that caution, within the different narratives that have been told about Artificial Intelligence. The differences between those narratives may hold the key to the multi-generational myopia that allowed technology to entrench itself so deep into our daily lives.

Perhaps the most common and – for better or worse – caricatured aspect of computer-related sci-fi media is that of the sometimes personified, often catastrophic sentient robot. This is the physical threat of Artificial Intelligence brought to life, the embodiment of our fear of an artificial uprising and beyond. Ranging from I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream to Avengers: Age of Ultron, the A.I. dictator is a simple yet ever-present reminder of the dangers of technology left unchecked. And though we all breathe a sigh of relief at every video of the Boston Dynamics robot dog falling over, Fahrenheit 451’s Mechanical Hound is closer than we think (Yang, 2024).

However, the act of looking for the Mechanical Hound itself may have been part of what let it in in the first place. The image imprinted onto us by story after story of a walking, speaking, and – most importantly – maleficent robot is perhaps so clear as to blind us to any other shape that such a phenomenon could take. Workers in all fields are increasingly finding that their work is being automated, and despite these changes having long been advertised as revolutionizing menial jobs and being a class-wide boon, that hasn’t seemed to alter the fact that it is those same workers who are now finding themselves getting the short end of the stick (Semuels, 2020).

“While it won’t be A.I. that devastates Earth, humans using A.I. very well might.”

Similarly, the hype around implementing a variety of robots in a variety of environments has left much room for improvement in regards to their sustainable development, a consequence that feels eerily similar to the unregulated damage of the Industrial Revolution or to the willful ignorance of the latter half of the 20th century (Hall, 2015). What these historical examples show us is that even though an evil hivemind is nowhere to be seen, you would not know it looking at the results. Human work is slowly starting to become obsolete, and the after-effects of such a shift are being felt in no small part by our planet (Nordgren, 2022). While it won’t be A.I. that devastates Earth, humans using A.I. very well might.

The other side of the Orwellian coin is, somewhat fittingly, surveillance. Even though invasive monitoring is a part of tech-dystopias that is often combined with the aforementioned tyrannical robot rebellion, it differentiates itself by being a far more passive form of ruination: constant supervision is portrayed as a natural endpoint of human actions rather than one shocking turn. Hardly surprising, then, that real life is so close to these seemingly inevitable stories. What is more surprising is that such a reality has been allowed to manifest at all. The resemblance of Big Data to quintessential dystopian settings is so uncanny as to be unremarkable, and the consequences are so alike those of physical Artificial Intelligence as to be indistinguishable.

“The foundation of a monumental change such as this was not built overnight, it will not be uprooted overnight either.”

And yet, there remains one key distinction: this feature is less primal, less visceral. The images of Big Brother’s watchful eye or that of a CCTV camera are not as evolutionarily ingrained as the material threats of competing species, metal or not. This division has meant that the barrage of speculative fiction on this topic has not, like its corporeal counterpart, been able to consolidate one representation of what such a threat would look like. This is, in part, because many of these now well-known threats would not begin to resemble their present form until much later. Instead, works in this field have muddied the waters. While full-scale robot revolution is the misdirection, surveillance has come to be the ace already up the magician’s sleeve.

The final act, however, is Generative Artificial Intelligence: a love-child of the physical threat of A.I. and the insidious one of mass surveillance. GenAI is AI that can create while learning and adapting—a quality which until recently eluded even the most advanced machines. It is a creation tantalizingly close to the intelligence which has been envisioned time and time again, and one which would have been impossible without the mass amounts of dubiously collected data that fuel its every letter. GenAI may be explicit enough in its similarity to warrant calls for global pauses (Future of Life Institute, 2023) and aggressive legislation, in the same way Facebook did at various points in the 2010s (Kelly, 2022, Kharpal, 2022). But just in the way the foundation of a monumental change such as this was not built overnight, it will not be uprooted overnight either.

By all accounts, the arrival of new and overwhelming technologies should not be a surprise. What established the ease in which they made this arrival, however, was the metaphorical loosening of the reins, the mistake of trying to put a face or name to our apprehension. The moment that same apprehension turns into expectation, every advancement needs only not to fit that dreaded silhouette in order to get a pass. With all eyes on the front door of civilization, waiting for the grand entrance of overlords and super-surveillance systems, Artificial Intelligence simply shuffled in through a hole in the wall.

References

-

Future of Life Institute. (2023, March 22). Pause giant AI experiments: an open letter. Future of Life Institute. https://futureoflife.org/open-letter/pause-giant-ai-experiments/

-

Hall, S. (2015, October 26). Exxon knew about climate change almost 40 years ago. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/exxon-knew-about-climate-change-almost-40-years-ago/

-

Hynes, M. (2021). The social, cultural and environmental costs of hyper-connectivity: Sleeping through the revolution (pp. 71–84). Emerald Publishing Limited.

-

Kelly, M. (2022, February 15). Meta’s Facebook to pay $90 million to settle decade-old privacy lawsuit. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2022/2/15/22935147/meta-facebook-privacy-like-tracking-data-settlement

-

Kharpal, A. (2022, December 23). Facebook parent Meta agrees to pay $725 million to settle privacy lawsuit. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2022/12/23/facebook-parent-meta-agrees-to-pay-725-million-to-settle-privacy-lawsuit-prompted-by-cambridge-analytica-scandal.html

-

Nordgren, A. (2022). Artificial intelligence and climate change: Ethical issues. Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1108/jices-11-2021-0106

-

Semuels, A. (2020, August 6). Millions of Americans have lost jobs in the pandemic—and robots and AI are replacing them faster than ever. Time. https://time.com/5876604/machines-jobs-coronavirus/

-

Yang, M. (2024, April 26). Ohio company to sell a “flamethrower-wielding robot dog” called the Thermonator. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2024/apr/26/robot-flamethrower-dog-thermonator

From the genesis of the ‘robot’ in Karel Čapek’s Rossum’s Universal Robots, the path of Artificial Intelligence and its future alongside humans has been a complicated one to piece together. Mankind’s fascination with the catastrophe an intelligent entity could bring about has left a vivid trail of disaster stories detailing the many ways that A.I. could destroy, turn against, or even surpass us. However, in a society becoming ever more aware of the strain brought onto us by the technology all around us, we are left wondering how such oppressive systems (Hynes, 2021) slipped past us despite our caution. The answer lies somewhere within that caution, within the different narratives that have been told about Artificial Intelligence. The differences between those narratives may hold the key to the multi-generational myopia that allowed technology to entrench itself so deep into our daily lives.

Perhaps the most common and – for better or worse – caricatured aspect of computer-related sci-fi media is that of the sometimes personified, often catastrophic sentient robot. This is the physical threat of Artificial Intelligence brought to life, the embodiment of our fear of an artificial uprising and beyond. Ranging from I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream to Avengers: Age of Ultron, the A.I. dictator is a simple yet ever-present reminder of the dangers of technology left unchecked. And though we all breathe a sigh of relief at every video of the Boston Dynamics robot dog falling over, Fahrenheit 451’s Mechanical Hound is closer than we think (Yang, 2024).

However, the act of looking for the Mechanical Hound itself may have been part of what let it in in the first place. The image imprinted onto us by story after story of a walking, speaking, and – most importantly – maleficent robot is perhaps so clear as to blind us to any other shape that such a phenomenon could take. Workers in all fields are increasingly finding that their work is being automated, and despite these changes having long been advertised as revolutionizing menial jobs and being a class-wide boon, that hasn’t seemed to alter the fact that it is those same workers who are now finding themselves getting the short end of the stick (Semuels, 2020).

“While it won’t be A.I. that devastates Earth, humans using A.I. very well might.”

Similarly, the hype around implementing a variety of robots in a variety of environments has left much room for improvement in regards to their sustainable development, a consequence that feels eerily similar to the unregulated damage of the Industrial Revolution or to the willful ignorance of the latter half of the 20th century (Hall, 2015). What these historical examples show us is that even though an evil hivemind is nowhere to be seen, you would not know it looking at the results. Human work is slowly starting to become obsolete, and the after-effects of such a shift are being felt in no small part by our planet (Nordgren, 2022). While it won’t be A.I. that devastates Earth, humans using A.I. very well might.

The other side of the Orwellian coin is, somewhat fittingly, surveillance. Even though invasive monitoring is a part of tech-dystopias that is often combined with the aforementioned tyrannical robot rebellion, it differentiates itself by being a far more passive form of ruination: constant supervision is portrayed as a natural endpoint of human actions rather than one shocking turn. Hardly surprising, then, that real life is so close to these seemingly inevitable stories. What is more surprising is that such a reality has been allowed to manifest at all. The resemblance of Big Data to quintessential dystopian settings is so uncanny as to be unremarkable, and the consequences are so alike those of physical Artificial Intelligence as to be indistinguishable.

“The foundation of a monumental change such as this was not built overnight, it will not be uprooted overnight either.”

And yet, there remains one key distinction: this feature is less primal, less visceral. The images of Big Brother’s watchful eye or that of a CCTV camera are not as evolutionarily ingrained as the material threats of competing species, metal or not. This division has meant that the barrage of speculative fiction on this topic has not, like its corporeal counterpart, been able to consolidate one representation of what such a threat would look like. This is, in part, because many of these now well-known threats would not begin to resemble their present form until much later. Instead, works in this field have muddied the waters. While full-scale robot revolution is the misdirection, surveillance has come to be the ace already up the magician’s sleeve.

The final act, however, is Generative Artificial Intelligence: a love-child of the physical threat of A.I. and the insidious one of mass surveillance. GenAI is AI that can create while learning and adapting—a quality which until recently eluded even the most advanced machines. It is a creation tantalizingly close to the intelligence which has been envisioned time and time again, and one which would have been impossible without the mass amounts of dubiously collected data that fuel its every letter. GenAI may be explicit enough in its similarity to warrant calls for global pauses (Future of Life Institute, 2023) and aggressive legislation, in the same way Facebook did at various points in the 2010s (Kelly, 2022, Kharpal, 2022). But just in the way the foundation of a monumental change such as this was not built overnight, it will not be uprooted overnight either.

By all accounts, the arrival of new and overwhelming technologies should not be a surprise. What established the ease in which they made this arrival, however, was the metaphorical loosening of the reins, the mistake of trying to put a face or name to our apprehension. The moment that same apprehension turns into expectation, every advancement needs only not to fit that dreaded silhouette in order to get a pass. With all eyes on the front door of civilization, waiting for the grand entrance of overlords and super-surveillance systems, Artificial Intelligence simply shuffled in through a hole in the wall.

References

-

Future of Life Institute. (2023, March 22). Pause giant AI experiments: an open letter. Future of Life Institute. https://futureoflife.org/open-letter/pause-giant-ai-experiments/

-

Hall, S. (2015, October 26). Exxon knew about climate change almost 40 years ago. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/exxon-knew-about-climate-change-almost-40-years-ago/

-

Hynes, M. (2021). The social, cultural and environmental costs of hyper-connectivity: Sleeping through the revolution (pp. 71–84). Emerald Publishing Limited.

-

Kelly, M. (2022, February 15). Meta’s Facebook to pay $90 million to settle decade-old privacy lawsuit. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2022/2/15/22935147/meta-facebook-privacy-like-tracking-data-settlement

-

Kharpal, A. (2022, December 23). Facebook parent Meta agrees to pay $725 million to settle privacy lawsuit. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2022/12/23/facebook-parent-meta-agrees-to-pay-725-million-to-settle-privacy-lawsuit-prompted-by-cambridge-analytica-scandal.html

-

Nordgren, A. (2022). Artificial intelligence and climate change: Ethical issues. Journal of Information, Communication and Ethics in Society, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1108/jices-11-2021-0106

-

Semuels, A. (2020, August 6). Millions of Americans have lost jobs in the pandemic—and robots and AI are replacing them faster than ever. Time. https://time.com/5876604/machines-jobs-coronavirus/

-

Yang, M. (2024, April 26). Ohio company to sell a “flamethrower-wielding robot dog” called the Thermonator. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2024/apr/26/robot-flamethrower-dog-thermonator